PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — Eve Glenn is on a mission to better understand addiction and to help create more effective treatments for alcohol and substance use disorders.

Glenn, a senior at Brown University, split her time growing up between Germany and Florida, and witnessed a number of friends fall into substance use dependencies. Glenn said she became accustomed to the sight of her peers walking to the village park in Stuttgart with a cigarette hanging from their lips and bottles of alcohol in their hands.

“The melting pot of culture and migration made it so that many of my closest friends were refugees seeking asylum from war-torn homes against mounting socioeconomic tension,” Glenn said. “I heard my friends’ stories and witnessed their challenges with drugs. This led me to realize how something as debilitating as addiction could so easily take hold.”

As she moved from Germany to the U.S., she said it felt as though the shadow of addiction followed her.

“The people, culture, reasons and substances of choice were always different, but the crippling effects of this disorder remained the same,” Glenn said. “My empathy for these individuals inspired an exploration of this widespread and personalized disorder.”

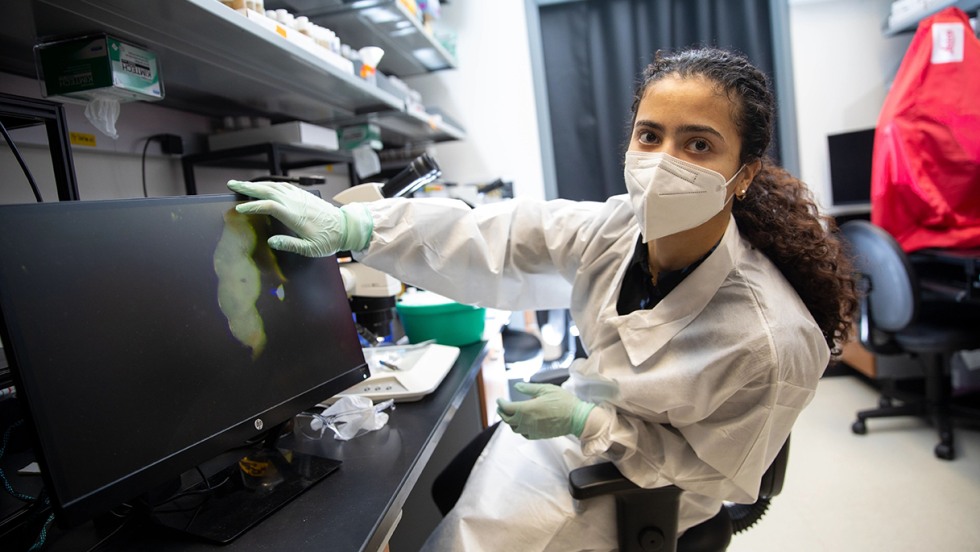

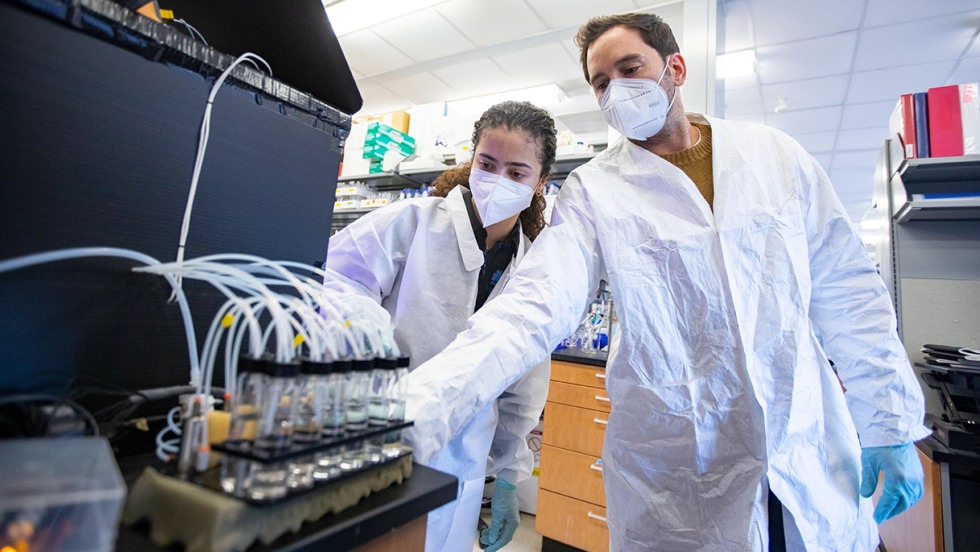

Glenn’s global background inspired her to pursue a neuroscience degree at Brown with a focus on neurobiological mechanisms of addiction and disease. Using the fruit fly as a model organism, Glenn is conducting independent research on self-administration and alcohol use disorders in the laboratory of Karla Kaun, an associate professor of neuroscience who is affiliated with Brown's Carney Institute for Brain Science.

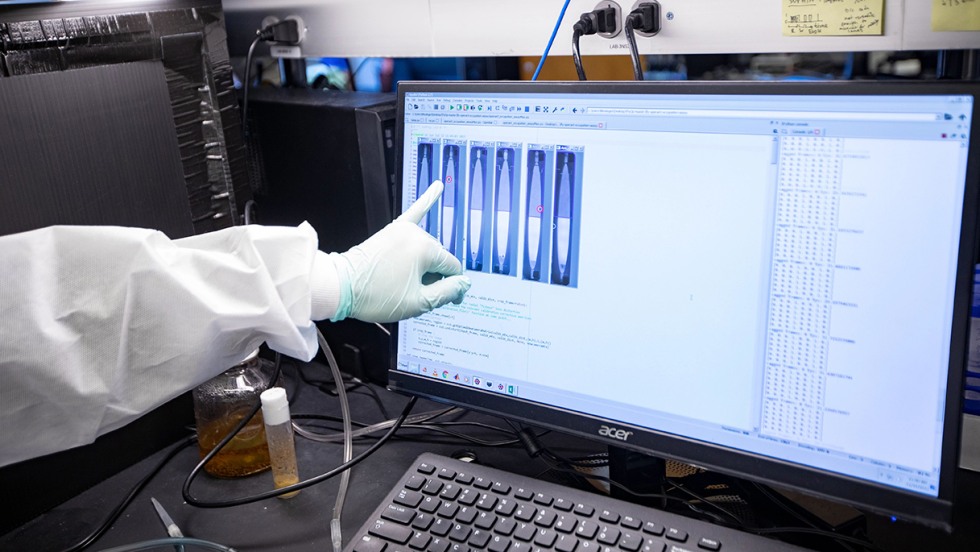

With its compact genome, tiny brain and a toolbox of sophisticated neurogenetic tools, the fruit fly is a powerful model organism to understand the neural substrate of behavior and investigate the underpinnings of drug reward at the molecular and cellular levels. Similar to the human mesolimbic pathway that plays a role in reward processing, the mushroom body of the fruit fly’s brain is implicated in responding to desirable and undesirable stimuli.

Glenn’s work delves into individual preference, allowing fruit flies to choose whether or not to self-administer ethanol, which is the main alcohol in beverages. In collaboration with researchers in the Kaun Lab, Glenn has identified a simple two-neuron circuit in the fruit fly’s brain that contributes to increasing ethanol self-administration. By inactivating the two neurons, she found short- and long-term changes in the fruit fly’s odor preference associated with alcohol intoxication.

“This is exciting as we now have an anatomical framework to investigate the structural and molecular changes associated with escalation of ethanol consumption,” Glenn said.