PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — “You ever hear the saying, ‘I didn’t see this coming?’” Mumia Abu-Jamal quipped.

The former journalist, activist and 41-year prison inmate joined a Brown University panel discussion on incarceration and the criminal justice system on Wednesday, Sept. 27, via a monitored and recorded prison phone line in Pennsylvania.

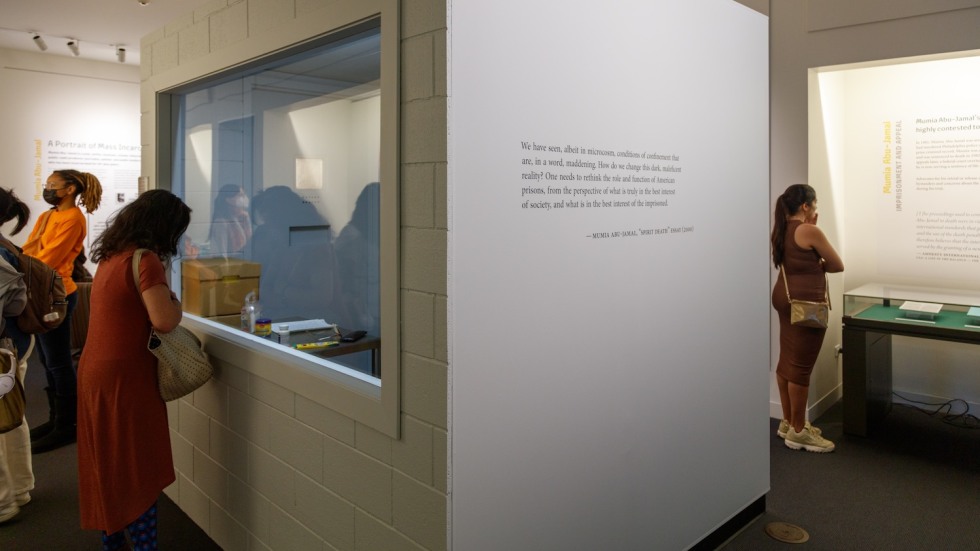

Abu-Jamal wasn’t just floored to be a central focus of the night’s conversation. He was also amazed to observe that four decades of his writings, artworks and possessions from prison — 97 boxes of them — were now available for reading and viewing at Brown’s John Hay Library, the centerpiece of one of the nation’s largest collections of the first-person accounts of incarcerated people.

“Welcome to a night at Brown, as we open the archives and thus turn a new page in history,” he said on speakerphone, addressing hundreds of in-person and virtual audience members. “It feels really remarkable… this was not foreseen.”

Comments from Abu-Jamal, who was convicted of murdering a Philadelphia police officer in 1981 and has since become one of the most outspoken incarcerated advocates for racial equity and criminal justice reform, kicked off “Voices of Mass Incarceration: A Symposium.” The three-day event at Brown was replete with performances and conversations focused on law enforcement, medical care in prisons, public art, the impact of incarceration on women and girls, and the history of incarceration; its events drew in diverse groups of activists and scholars from across the globe and Brown and Providence community members.

Jointly hosted by the Brown University Library, the Pembroke Center and the Ruth J. Simmons Center for the Study of Slavery and Justice, the symposium also marked the public opening of the Abu-Jamal archives and the beginning of a year-long exhibition on mass incarceration extending across the Brown campus.