PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — While pandemic lockdowns helped mitigate the spread of COVID-19 to save lives, experts recognized later that they had other negative repercussions. Before the next pandemic, members of Brown University’s School of Public Health community are collaborating to develop a more targeted way of stopping disease spread that would allow life to proceed as usual — or at least without isolating individuals and shutting down as many communal spaces.

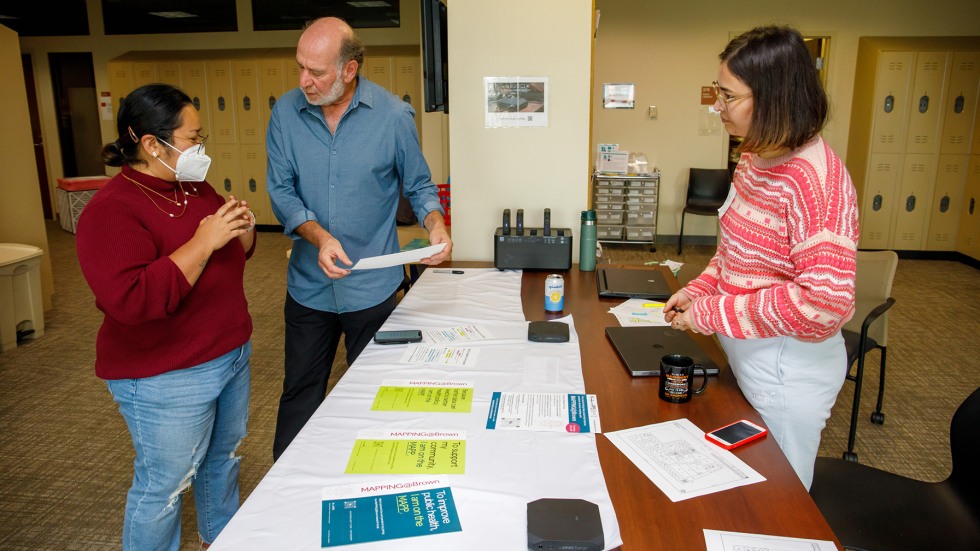

The project, called MAPPING@Brown, uses a smartphone app to study social interactions to determine how they shape disease transmission patterns. It involves tracking individual and crowd movements as well as social mixing — how, where and for how long people come together.

“Because infectious pathogens spread from person to person, our social interactions shape disease transmission patterns,” said Mark Lurie, an associate professor of epidemiology at Brown who is leading the Mobility Analysis for Pandemic Prevention Strategies (MAPPS) project.

A native South African, Lurie is an infectious disease epidemiologist who specializes in studying HIV/AIDS, sexually transmitted infections and tuberculosis in sub-Saharan Africa. A common thread in his research is understanding the role of human migration and social interaction in epidemic spread. There’s currently little information on how many interactions people have in a day, Lurie said, and models of disease spread are mathematical computations often based on the assumption of random mixing.

“We’re attempting to pinpoint people’s place in space and time, and therefore their social interactions, to create more accurate predictive models based on observed human behavior,” Lurie said.

The project findings, he said, are intended to help inform public health responses to future pandemics.

“With fine-grained data on social interactions and effective predictive models, we could really understand in detail which behaviors are safe during a new pandemic and which are not,” Lurie said. “For example, should we make stairwells one-way? Should class size be limited, or the hours of operation of the cafeteria be expanded to decrease the density of mixing? These are the kinds of questions we will finally have some evidence to help answer.”

From Nov. 6 to 19, MAPPING@Brown is charting the social network within Brown’s School of Public Health building at 121 South Main St. in Providence. Participation is open to members of the public health community who spend any amount of time in the building, and each participant who opts in downloads a custom-created MAPPS app that shares data with the research team.