PROVIDENCE, R.I. AND LEAD, S.D. — There is more to the universe than meets the eye. Dark matter, the invisible substance that accounts for 85% of mass in the universe, is hiding all around, and figuring out exactly what it is remains one of the biggest questions about how the universe works.

On Monday, Dec. 8, researchers with the LUX-ZEPLIN (LZ) dark matter experiment announced new results in the search for one of the prime dark matter candidates: weakly interacting massive particles, or WIMPs. While the 417 live days of data taken by the detector in this latest analysis turned up no signs of WIMPs, the new findings put the tightest constraints yet on the energy parameters of low-mass dark matter interactions.

And the detector did pick up signals from another type of weakly interacting particle — solar neutrinos. Neutrinos have been detected previously by other means, but this was the strongest neutrino signal yet from a dark matter experiment, which is a testament to LZ’s sensitivity in this mass range, the research team says.

“We have been able to further increase the incredible sensitivity of the LUX-ZEPLIN detector with this new run and extended analysis,” said Rick Gaitskell, a professor of physics at Brown University and the spokesperson for LZ. “While we don’t see any direct evidence of dark matter events at this time, our detector continues to perform well, and we will continue to push its sensitivity to explore new models of dark matter. As with so much of science, it can take many deliberate steps before you reach a discovery, and it’s remarkable to realize how far we’ve come. Our latest detector is over 3 million times more sensitive than the ones I used when I started working in this field.”

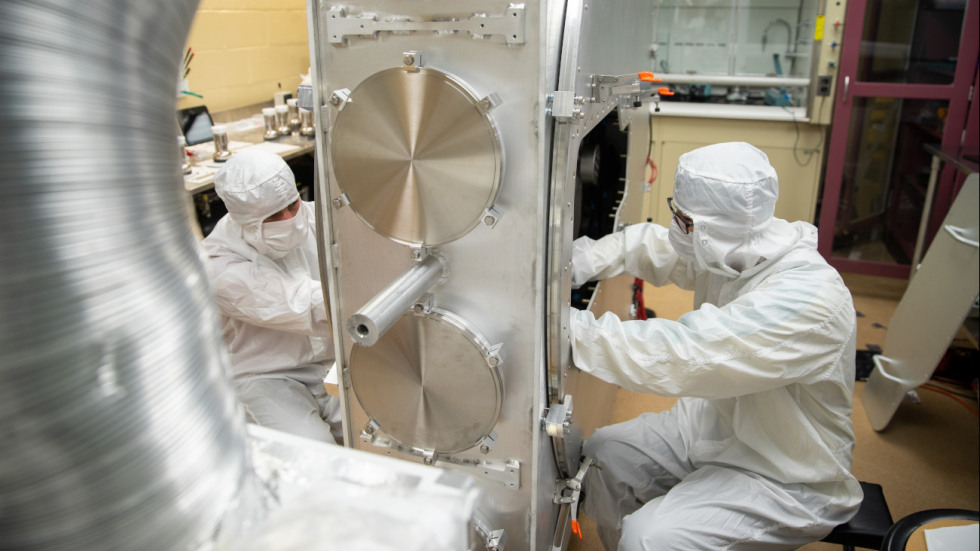

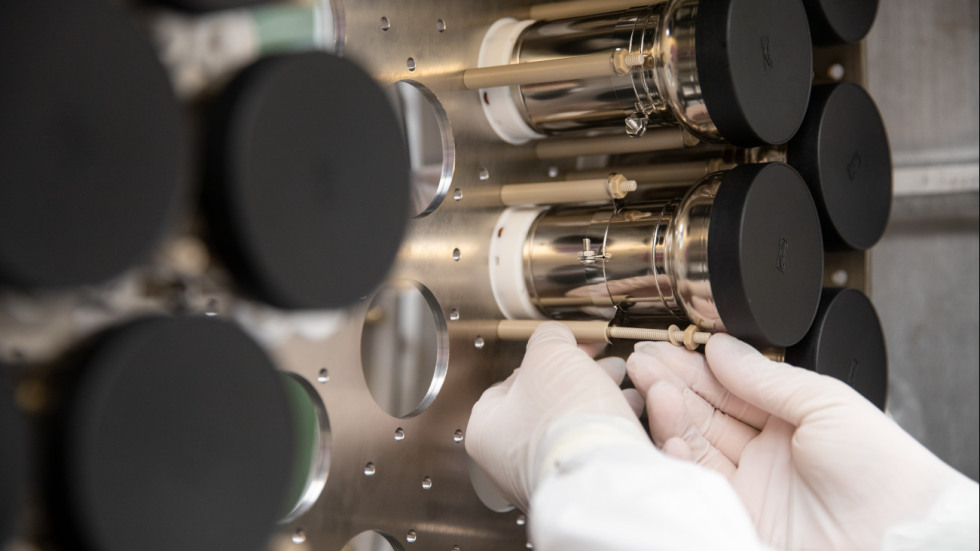

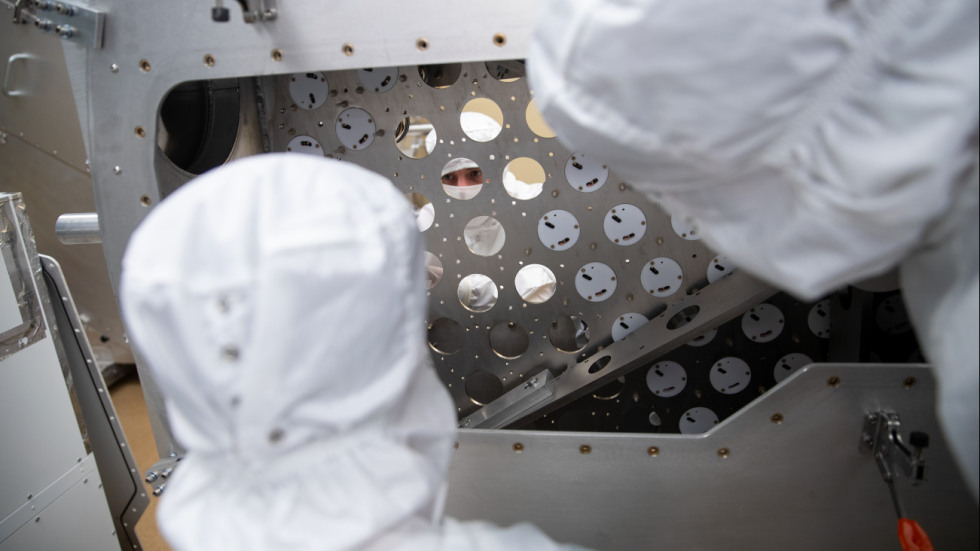

LZ is an international collaboration of 250 scientists and engineers from 37 institutions. The detector is managed by the U.S. Department of Energy’s Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory and operates nearly a mile below ground at the Sanford Underground Research Facility (SURF) in South Dakota.

The new results use the largest dataset ever collected by a dark matter detector. The analysis, based on data taken from March 2023 to April 2025, probed a mass range between 3 and 9 GeV/c2 (gigaelectronvolts divided by the speed of light squared) — or roughly three to nine times the mass of a proton. It’s the first time LZ has looked for WIMPs below 9 GeV/c2, and the results further narrow the possibilities for what dark matter might be and how it may interact with ordinary matter. The research was presented in a scientific talk at SURF and will be released on the online repository arXiv. The paper will also be submitted to the journal Physical Review Letters.

Dark matter has never been directly detected, but its gravitational influence shapes how galaxies form and stay together. Without it, the universe as it’s known today wouldn’t exist. Because dark matter doesn’t emit, absorb or reflect light, researchers have to find a different way to “see” it.