PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — Amid the festivities of Brown University’s graduation in May 2015, Dima Amso, associate professor of cognitive, linguistic and psychological sciences, sat down for lunch next to Professor Beshara Doumani, director of Middle East Studies at the Watson Institute.

It was not serendipity, as Doumani first thought. Instead, Amso had attended several Middle East Studies events on Syria and was now seizing the opportunity to propose an unusual collaboration. Now, less than a year later, that collaboration has attained international proportions with a conference at Brown on April 8 and 9.

“Since 2011, many of us have been watching the situation in Syria with growing alarm — it’s a major crisis — and wondering, maybe privately, what we can do,” Doumani said. When Amso appeared at the lunch table, he said, “We got to talking and quickly established that we were both thinking about what we can do. Meeting with Dima was an unbelievable catalyst.”

The pair’s goal, now shared among a team of five brain science and Middle East experts at Brown, has been to learn how their scholarship and science could help people who are providing aid to refugee children from Syria and, perhaps, around the world. They have never presumed they know what to do. Instead their approach has been to engage with those who are already helping, to understand how they could contribute.

The team gathered at an International Relief and Development office in a refugee camp (l. to r.): Tala Doumani, Beshara Doumani, Carl Saab, Dima Amso, and Sarah Tobin.

Image courtesy Tala and Beshara Doumani

From the start it was clear to Amso, who studies how early life stress, such as living with socioeconomic disadvantage, can affect cognitive and behavioral development in children, that while many aspects of the underlying science are universal, the contexts in which she hopes to apply them are not. Her work mostly takes place in Providence, where stresses for many children are very real, but very different than those among Syria’s millions of refugees.

But Doumani, Joukowsky Family Professor of Modern Middle East History, focuses much of his scholarship on family and social history, particularly among Syrians and Palestinians. Moreover, the associate director in Middle East Studies, Sarah Tobin, was already working closely with Syrian refugee communities in Jordan, for instance to investigate how the reality of refugee life was being portrayed — and often skewed — in Western media.

During the fall, the group grew further to include Dr. Carl Saab, neuroscience and neurosurgery associate professor (research), who studies pain, which is a source and form of stress, and its effect on the brain. He already knew Doumani and Amso, so when she called, he needed no time to see how meaningful the effort could be.

“From the first words that she uttered I immediately recognized this would resonate with my scientific interests, but also I was born and raised in Lebanon, so I have seen humanitarian crises on a global scale,” Saab said.

The group also included third-year international relations concentrator Tala Doumani, Beshara Doumani’s daughter. Initially Tala was to shadow the team, but her previous experiences in working with Palestinian refugees and her academic work on international humanitarian organizations made her an active member. She had hoped to become involved with helping Syrian refugees as that crisis grew.

In January, the quintet took a 10-day fact-finding trip to Jordan to understand the urgent situation there firsthand and to open a dialogue with staff members of governmental and non-governmental organizations and the United Nations who were working with children both in refugee camps and in Jordanian host communities.

“We kind of went in saying, ‘What are the correct questions that we should be asking?’,” Tala Doumani said.

Their fieldwork was funded by Amso’s James S. McDonnell Scholar Award in Understanding Human Cognition.

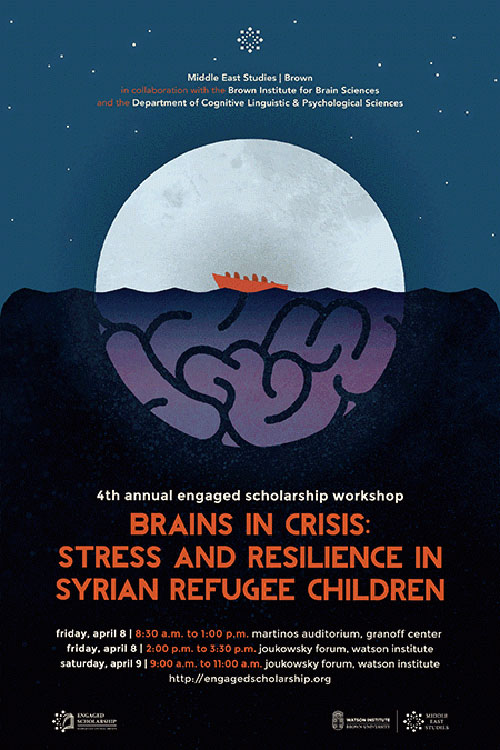

‘Brains in Crisis’ conference

With the conference “Brains in Crisis: Stress and Resilience in Syrian Refugee Children,” they will expand the dialogue they began in Jordan. Some of the leading humanitarian aid providers they met in Jordan will come together with scientists from Brown and beyond to explore how to best strengthen the ties between basic brain science research and refugee aid efforts. The goal is to develop a model that can make basic research findings applicable in aid work that addresses mental health and child development.

“From a scientific perspective, the impact of stress on the brain is going to be more significant and more tremendous on kids vs. adults, in that this represents also a latent, long-term problem that could be easily missed,” Saab said. “It’s something we can’t touch and can’t see currently but will be manifest later and probably have a magnified effect later on.”

Early-life stress, Amso said, can disrupt the timing of development, and can lead to depression, anxiety and difficulty learning. Prevention is generally more effective than treatment.

The conference will feature international experts on the science of stress and development such as Drs. Bruce McEwen of Rockefeller University, Megan Gunnar of the University of Minnesota, Martha Farah of the University of Pennsylvania, and Audrey Tyrka of Brown. They’ll speak side by side with people who are providing assistance on the ground in Jordan such as Frank Roni, child protection specialist for camps at UNICEF Jordan, and Dr. Marcia Brophy, regional mental health and psychosocial support specialist for Middle East and Eurasia at Save the Children International.

Brown University President Christina Paxson, who has studied how economic disparities, and acute crises such as Hurricane Katrina, affect the well being of children, will speak as well.

Middle East Studies is organizing, staffing and partially funding the conference, which will be live-streamed . Additional support comes from Brown Institute for Brain Science, directed by Professor Diane Lipscombe, and the Department of Cognitive Linguistics and Psychological Sciences, chaired by Professor William Heindel.

January in Jordan

Some of the conference speakers are people that the team met when they were in Jordan. Tobin helped the team make many of the connections they needed to make the trip productive immediately.

“In the last few years I’ve developed a lot of contacts among Jordanian officials and NGO workers,” Tobin said. “When this started coming together I already had a number of colleagues that I knew that were willing to help.”

Amso adds that in the Zaatari refugee camp, “They knew Sarah’s favorite foods and how she takes her tea.”

It was crucial for the team to observe what life was like for children and their families, and to understand the intricate intersections of aid efforts and fledgling institutions in the camp, where about 80,000 refugees live, and in host communities, where another 1.2 million refugees have come. They come from many different parts of Syria and from many backgrounds. At one point Amso, who is Syrian, met a woman who came from the same town as she.

Understanding the diversity of backgrounds among children is vital because broad cultural categories that refugees may share aren’t enough to predict how children might respond neurodevelopmentally to the stresses of refugee life. If a young refugee is not in school in Jordan, is that a stressor? Maybe it would be for a child who had been in school in Syria, but maybe not in the same way for another child who had not been in school before the war.

“The experiences of a child at 5 Main Street are not the experiences of a child at 7 Main Street,” Amso said.

Beshara Doumani refers to that as the “irreducible singularity of every individual.”

“This team is an experiment in forging connections between the humanities, social sciences, and the sciences,” he said. “With no illusions about the often negative aspects of humanitarian intervention, and with the clear recognition that a full understanding of the complexity of daily experiences is key to scientific work, our team spent many months preparing for the trip.”

They read reports, interviewed NGO workers via Skype, and engaged in discussions about the ethical and political dimensions of the project. The trip, Beshara Doumani said, revealed that it is important for interdisciplinary conversations to begin at the most basic level of critically examining what questions are being asked and why.

One important way that context varies independently of broader culture is that, since the Zaatari refugee camp opened in 2012, more than 5,000 babies have been born there, meaning that the refugee crisis has gone on so long that many children haven’t yet known another life. Their context is different than that of even their older brothers and sisters.

Thousands of children live in difficult conditions in camps like Zaatari. More than 5,000 babies have been born there.

Image: Carl Saab

Beshara Doumani said that it became evident from the visit that the school systems and the ways they engage refugee children are woefully inadequate and still in flux. The Jordanian government, the United Nations and NGOs, for example, appear to have different approaches to working with refugee kids.

Many services to the refugees are administered ad hoc. Syria’s civil war wasn’t supposed to go on this long, Amso said.

But by forging connections, both in Jordan and through this month’s conference, the team hopes to develop ways that the findings of basic science can play a meaningful role in how the diverse institutions and groups serving refugees approach aid. If they can build a meaningful bridge from basic neuroscience and psychology labs all the way to the children of Zaatari and camps and communities in Lebanon and Turkey, too, maybe those same blueprints can also allow science and scholarship to contribute in other refugee situations, as well.

“We can start with this refugee crisis, but if it’s well done then it becomes a model for any crisis,” Amso said. “The model can exist and the details will follow the particulars of the problem that’s being faced.”

Refugee crises around the world, after all, have not been few or far between in recent history.