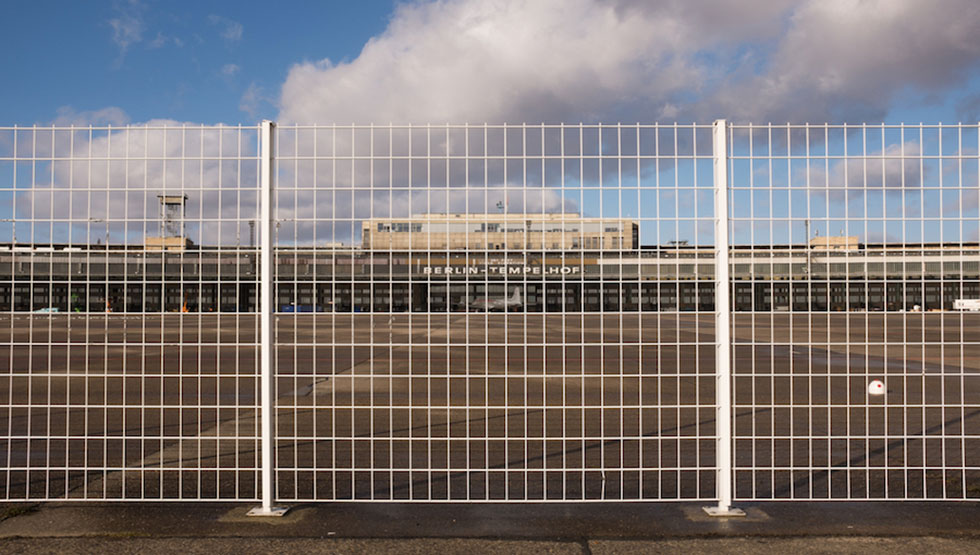

Exterior of Tempelhof Airport in Berlin, Germany

hinterhof / Shutterstock.com

PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — For the 18 members of the Brown Jazz Band, spring break offered the opportunity to travel to Berlin and perform at such legendary spaces as the Zig Zag Jazz Club and the Stummfilmkino Delphi.

Yet performing for audiences at a decidedly different venue was at the heart of the band's trip: two 52-foot-tall hangars at Tempelhof Airport, now a temporary home to some 7,000 refugees from Syria, Afghanistan, Iraq and elsewhere.

Michael Steinberg — Brown’s vice provost for the arts and president-elect of the American Academy in Berlin — first suggested that there might be an opportunity to stage performances for the refugees.

“Once it was mentioned as a possibility, the students saw it as the most important part of the trip,” said Matthew McGarrell, senior lecturer in music and the director of the Brown Jazz Band.

image: Luyuan Xing

Arranging for a group of student musicians to perform at Tempelhof — a massive decommissioned airport complex in the heart of Berlin known in the 1930s as the entrance to Nazi Germany — proved no simple task. Concerns for the refugees’ safety and privacy limits movement among the hangars, requires that any visitors be carefully vetted and imposes limits on photography or recording.

The students were unfazed, Steinberg said, and devised ways to work around limitations like the lack of amplification and the impossibility of having a piano for the performance. Before leaving for Berlin, students made efforts to secure battery-operated amps and a melodica, a portable substitute for a piano.

“They really wanted to do this,” Steinberg said. “Playing for the refugees was at the top of their list.”

Steinberg worked with Pamela Rosenberg, a former managing director of the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra who has served as an external advisor for Brown’s Cogut Center for the Humanities. Having set up arts and music programming for refugee children at Tempelhof and elsewhere in Germany, Rosenberg was a critical partner. Rosenberg said her project, tentatively titled Musikprojekt Hangar 7 in Tempelhof, helps prepare refugees to integrate into German society.

“Music is a bridge to integration and collaboration between refugees and teachers and, later on, to the local community,” she said. “Music helps children develop communication skills, bond with others, and acquire non-verbal knowledge about other cultures. But, as we also sing with the children, it has the add-on effect of helping them to learn the German language.”

Rosenberg worked closely with German authorities to arrange for the visit. The jazz band played in two hangars, moving and setting up twice because the refugees are generally required to stay in the hangar where they reside. The students knew that they would be playing in an open area without amenities or the typical acoustic properties of a performance space, but they did not know what kind of reception they would get. Alex Han, the Jazz Band’s pianist who brought his melodica on the trip, said that he felt self conscious at the start.

“We had the privilege of freely coming and going to this place by choice, and moreover, to play music,” he said. “The thoughts that I normally have before a performance — hitting all the notes, taking cool solos, having stage presence, etc. — felt frivolous and inconsequential. I worried about how we would be received. I didn't want to feel like we were trivializing the situation these refugees were in.”

During the first set in Hangar 7, the musicians quickly discovered that they would not have the opportunity to do a sound check or rehearse. In part because the band was accompanied by Rosenberg, a familiar face and someone whose presence signifies that something is about to happen, the children began setting up plastic chairs and piling onto benches in front of the performance area in anticipation. The band launched into the set and was immediately met with women and children keeping time with their hands. The children’s energy was infectious.

Dana Gooley, an associate professor of music at Brown who joined the band on the trip, sat among the spectators during the performance. He said that the beginning of that first concert was “a particularly poignant moment for me. The moment the band started, all the kids started clapping along, and soon we were all clapping too.”

Han said the applause was overwhelming: “A few songs in, not only the kids were clapping along and cheering, but the whole audience seemed engaged and happy. The adults that seemed skeptical and stoic before the performance were shouting for an encore. The fact that we could provide that kind of joy by doing something we loved was very powerful and incredibly rewarding.”

McGarrell agreed.

“The opportunity to play at Tempelhof was one of the most beautiful experiences I have enjoyed in 40 years of teaching,” he said. As a teacher, he witnessed his students contend with difficult performance conditions gracefully and resourcefully. “The real stars, however, were the residents of Tempelhof, who accepted our music (and us) and gave us their support and appreciation generously,” McGarrell added. “It’s hard to imagine that there were many jazz fans in the audience, but from the first notes, they were with us. They made us feel like we belonged.”

The social worker on duty told Rosenberg that she had tears in her eyes to see the refugees so happy, Rosenberg said. “Otherwise, they are in limbo, waiting for their ‘official documents’ and to see what the next step in their lives is going to be. They don’t have money to go out and enjoy all that Berlin has to offer.”

As the global community confronts the refugee crisis and the Brown community finds ways to address the needs of refugee populations in different ways, experiences like the performance at Tempelhof make clear that refugees are far from a homogeneous population. Luyuan Xing, program coordinator for the arts in Brown's provost's office who traveled to Berlin with the group, was approached during the performance by refugee from Vietnam who was fleeing poverty rather than war, and whose journey to get to Tempelhof, he told her, had taken eight years.

McGarrell was asked by two Tempelhof residents to connect on Facebook.

“It was only later that I realized that each of their Facebook apps used different alphabets, neither of which I understood,” he said. “It struck me that, in many ways, the residents of Tempelhof are as different from each other as they are from me. Yet there we were, playing, singing and moving together in one big jazz jam.”