PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — For more than four decades, Barry Prizant has worked as a clinical scholar, researcher and consultant to persons with autism spectrum disorders (ASD). Through his 2015 book “Uniquely Human: A Different Way of Seeing Autism,” and a new musical theater and arts program at Brown, Prizant continues to impact the way ASD is understood and treated.

Currently an adjunct professor of theatre arts and performance studies, Prizant has worn many hats at the University, including associate professor in child and adolescent psychiatry. A licensed speech-language pathologist, Prizant founded and directed the communication disorders department at Rhode Island’s Bradley Hospital and has developed graduate educational programs as well as family-centered programs. He consults with schools and agencies internationally.

For National Autism Awareness Month, he shared his thoughts on changes in the field and his newest venture.

Your work with individuals with ASD and communication disorders spans more than 40 years. How did you get involved in the field?

I started as a teen working at summer camps with people with autism and disabilities. I went in pretty raw, without academic or clinical training. I was essentially a caregiver and was responsible for keeping people healthy and happy in the summertime. In college, I became a linguistics and psycholinguistics major looking at the psychological basis of language and communication disorders, during what was called the psycholinguistic revolution. I eventually got my master’s and then my doctorate in communication disorders. Having worked at the residential camps for six summers in a row formed the foundation for who I am as a professional. A lot of the academic material I was reading about ASD was not what I was experiencing with people. The predominant “deficit-checklist” approach viewed ASD through the lens of pathology, and academics were not seeing people on the autism spectrum as full, balanced people who had strengths as well as challenges.

What is a “deficit checklist” approach to ASD?

Throughout the years, researchers used terms to describe “autistic behavior” as “deviant, pathological and meaningless speech” — all negatively toned ways of talking about how people with ASD behave and try to communicate. Treatment was directed toward restricting or eliminating behaviors like jumping, flapping, spinning and staring at your fingers, or echolalia, which is a tendency to repeat what people say.

I saw such behavior as unconventional, but it didn’t mean that it wasn’t purposeful and functional. Our job was not just to get rid of these behaviors, but instead to say: “Wait a minute, these people do these things to cope. We need to understand these behaviors as part of a system these kids have to try to participate in conversation.” Spinning can help someone with ASD stay alert. Echolalia can help autistic people learn how to talk. A lot of people with ASD now tell me directly that, “yes, I used echolalia, and that’s how I learned to talk.” It is so validating, because for so many years, people tried to guess what persons with ASD were experiencing.

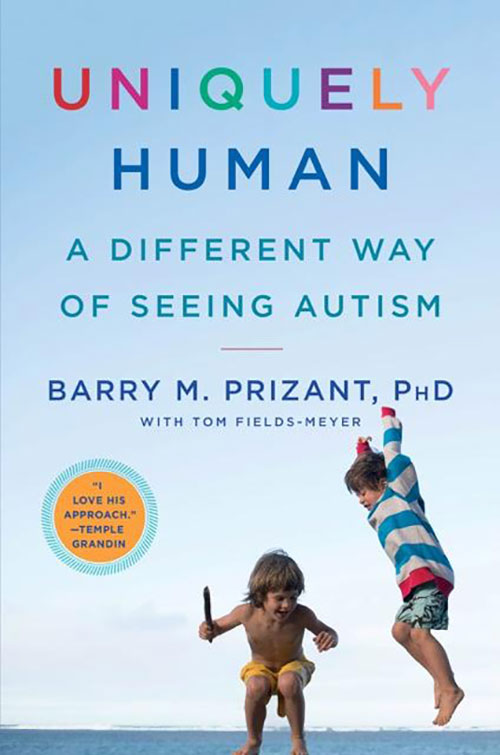

“Uniquely Human: A Different Way of Seeing Autism” came out last year. Can you talk about the ways autism is generally perceived and how your book suggests ASD be viewed and understood?

Our understanding of ASD is evolving and changing rapidly, and I hesitate to generalize, but in the past, you heard statements like, “people with autism are in a world of their own,” or “they’re not interested in relationships with people.” A well-known book described autism as “a lost, hellish world”, and that people are trapped in this hell. In other words, autism is nothing but a tragedy for the affected person and his or her family. A lot of the self-stimulatory behavior was viewed as attempts by people with ASD to push people away to maintain solitude. Many things posited are being overturned, because we now know they are grossly inaccurate.

I argue in my book that autism is a different way of being human. Children with autism are progressing through developmental stages as we all do. To help them, we don’t need to change them or fix them. We need to work to understand them and then change what we do. Our everyday lives are busy, crazy and fast, with too many layers of social etiquette and social understanding. We need to understand that this is difficult for people with ASD, whose neurobiology makes them honest and direct and literal, and highly sensitive and vulnerable.

Although people with ASD are very different from one another, they generally want to make personal connections, but some situations can be so overwhelming that they are not able to put in the additional effort of socializing. Persons with ASD, especially those who are older, are telling us us a lot about what we don’t understand. They say, “I wanted to have friends, but I just didn’t know how to do it.” And we shouldn’t think people with ASD lack empathy or feelings. They might have more intense emotions than a neurotypical person — so intense and upsetting, in fact, that they can’t modulate them.

Parents have made statements about your book changing the way they relate to their children with ASD. Do you hope that it will impact how people with ASD see themselves?

Absolutely. Parents will tell you that rather than being unfeeling or insensitive, their children are hypersensitive. They may have low self esteem because they are always being told what they are doing wrong, and depression is very common. I hear directly from people with ASD through notes, Facebook posts or in face-to-face encounters. They say thank you for your book. Too often what autistic people say is given less credibility than what researchers say about ASD. Temple Grandin was the only voice and source of the ASD perspective for decades. There is a young autistic woman named Chloe who is now beginning to present at conferences. She told me, “I love your book. I take it with me everywhere and show to everybody. It explains me more than I can explain me.”

You are developing a theatre and musical arts program for autistic children and adults at Brown with Julie Strandberg, senior lecturer in theatre arts and performance studies; Rachel Balaban, adjunct lecturer in theatre arts and performance studies; and Elaine Hall, the founder and director of the Miracle Project. Can you talk a bit about this?

I have been long-time friends with Elaine, whose Los Angeles-based the Miracle Project and Emmy award winning documentary “Autism: The Musical”, teaches a lot about autism and the family experience. Elaine is also a mother of a 22 year old son with ASD. At Brown, Julie and Rachel and their students already work with populations with Parkinson’s disease and autism in Artists and Scientists as Partners. We said, “Why don’t we think about Brown being the east coast and academic home of the Miracle Project, where we could bring people from all over the world to be trained by Elaine and her staff?”

It fits beautifully with the “Uniquely Human” philosophy by shattering some of the myths surrounding ASD and opening opportunities. Why do we want kids to be in theatre and performing arts? It’s about a community of kids growing together and learning together. What we’re doing in the Miracle Project is everything people have said for years that people with autism cannot do. The repercussions — beyond just a kid being on a stage and performing with other kids — are great. Parents can see their kids on stage and be proud of them, when all they’ve heard for years is how difficult their children are. We will create a safe and loving space and build social and communication skills and self-esteem. We are in the middle of a revolution. We are totally shattering misconceptions about ASD, and building new understandings.