PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — Earlier this month, director Steven Spielberg announced that his next film will tell the story of a six-year-old Jewish boy seized from his home in 19th century Italy, raised by the Pope as his own and ordained into the Catholic priesthood – a plot that can compete with the best of today’s fiction.

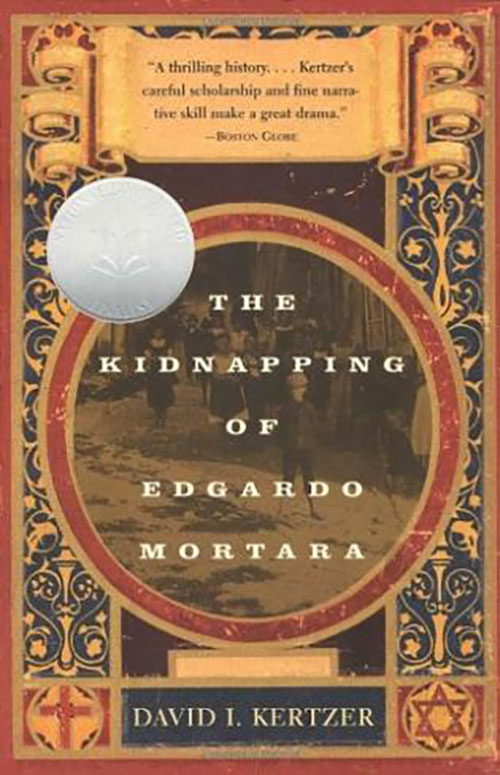

Except the story is very much not fiction. Rather, it’s the true story chronicled in “The Kidnapping of Edgardo Mortara,” a 1997 nonfiction book published by Brown’s David I. Kertzer that Spielberg will adapt for the film.

In the movie, scheduled to be shot and released in 2017, Mark Rylance will play Pope Pius IX. Tony Kushner, who like Kertzer is a Pulitzer Prize winner for other projects, is writing the screenplay.

Kertzer — the Paul R. Dupee, Jr. University Professor of Social Science, a professor of anthropology and Italian studies and Brown’s provost from 2006 to 2011 — shared his thoughts from Italy, where he is on sabbatical.

“The Kidnapping of Edgardo Mortara” debuted nearly two decades ago. When did you learn of Spielberg’s interest?

The book was first optioned to other filmmakers right after it came out in 1997. There is a long saga here, but the film did not get made. At the end of 2007, when Tony Kushner was working with Steven Spielberg on “Lincoln,” Tony gave Spielberg a copy of my book, telling him he would enjoy it. A few weeks later, Spielberg called me and we spent an hour on the phone. He told me he was eager to make the book into a film, and soon thereafter decided to ask Tony Kushner, whom I have known for 20 years or so, to write the screenplay. I, of course, was thrilled.

Your book has been described as “a historical thriller” as well as “an authoritative analysis of how a single human tragedy changed the course of history.” When you were writing, did you imagine any of the scenes unfolding cinematically?

Well, I did title one chapter “A Servant's Sex Life!” But my concern was to write a book based on original archival research that would attract a broad audience. The historical episode was hugely important, but largely forgotten. That said, I did have in the back of my mind that the book could make a great film if done by the right person. I don’t think, though, that this affected my writing. But attracting a broad audience to a book of history means writing in such a way as to make the story vivid, to bring the characters and the scenes to life. In a sense, this is not different from writing that lends itself to film.

Do you have any concerns about how the process of turning your nonfiction work into a film — decisions about the cast, script, cinematography and editing, for example — will affect the understanding of the historical scholarship that underpins the narrative?

When different filmmakers have contacted me over the years, this has been an important consideration in deciding about with whom I might entrust a film based on my book. We have all heard horror stories. One reason I am so happy about the Spielberg film is my great faith in both Spielberg and Tony Kushner. I have had many long conversations with Tony and know how committed he is to making sense of the historic context, giving a sense of the historical importance of the events, and getting the history right.

Will you have a role in the film as it goes forward?

Although nothing is yet finalized, I believe I will continue to serve as the historical consultant.

Edgardo Mortara's story fueled public outrage in the U.S. and Europe that gave momentum to political efforts to create a unified, secular Italian state. Now the film will bring the story to a contemporary audience. Do you think that filmgoers will be surprised that the Catholic church took this kind of action just 160 years ago?

Few people realize that the Inquisition was still operating through the 19th century, and that where the pope had police powers, as he did in the Papal States, Jewish children were still being regularly seized by the church from their parents in cases of forced baptism of the sort my book recounts.

Why do you think the Mortara case, as opposed to stories of other Jewish children taken by the church, become so well known?

For centuries in Italy, small Jewish children were regularly taken from their parents based on claims of secret baptism by Christians, and outside of the Jewish community, no one seemed to care. In the Papal States, the Jews had no civil rights, and of course there was no freedom of the press. But in 1848 the Jews of northwestern Italy — the Savoyard kingdom — were liberated and began to have their own press. By this time, too, the Jews in France and Britain had been given equal rights and had their own press. The battle for unification had also begun with a revolt against the pope in 1848, and it had as its watchword the need to separate church and state. The result was that not only was the world’s Jewish community able to organize on behalf of the Mortaras, but the major figures involved in Italian unification, such as Count Cavour and the Emperor Napoleon III, became involved.

A great deal of media coverage followed Spielberg’s announcement that he would adapt your book. Were you surprised by what you read in any of the reporting?

It seems that thousands of stories characterize my book, on which the film is based, as a novel. I had always wanted to be a novelist, so this has been perversely gratifying, especially since papers such as "Le Figaro" in France and "The Independent" in Britain credit my “novel” with having been awarded a Pulitzer Prize. In short, overnight I became not only a novelist, but a Pulitzer Prize-winning novelist.