PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — In a bright classroom in the Elmwood section of Providence, four sixth graders and one fifth grader sit in a circle and debate the meaning of the word “feud.”

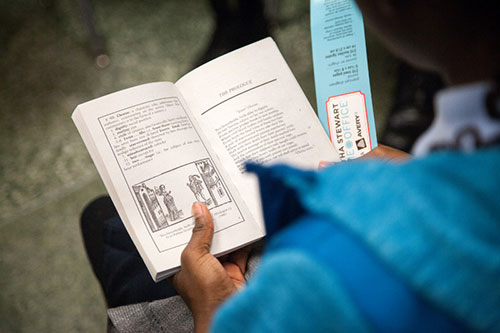

As the girls grapple with the prologue of William Shakespeare’s play “Romeo and Juliet,” they call upon the reference points at their disposal, among them the television show “Family Feud,” their recent studies on the Civil War, and the children’s book series “Magic Tree House.” One student, Ashley, parses the prologue’s first line: “Two households, both alike in dignity.”

“I think that the two families are sort of the same, with the same amount of money, and they hate each other equally, but maybe they have some of the same kinds of opinions,” she says. The other students take up the thread to analyze the next 13 lines.

By the end of the hourlong session, they have defined “mutiny,” “civil,” “star-crossed” and “noble,” learned the rhyme scheme of a sonnet, worked out how Shakespeare might have acquired knowledge of Italy in a time before TV or the internet, and started brainstorming ideas for writing their own sonnets.

The students, who attend Sophia Academy, are participating in a program called ¡Shakespeare para todos! (Shakespeare for everyone!) in which graduate and undergraduate student volunteers from Brown teach “Romeo and Juliet” in Spanish and English to fifth, sixth and seventh graders at DelSesto Middle School, Roger Williams Middle School, Leviton Dual Language School and Sophia Academy in Providence.

Since February, the seven Spanish-speaking Brown volunteers, overseen by faculty from Brown’s departments of English and Hispanic studies, have worked with the middle schoolers to interpret “Romeo y Julieta” and to create adaptations of the play ranging from raps and songs to poems and dramatic scenes. Some of these pieces will be performed at the El Día de los Niños celebrations at Knight Memorial Library on April 30, while others will be presented in the schools at the end of the academic year.

Supported by a Rhode Island Council for the Humanities mini-grant, the program was conceived of by Coppélia Kahn, professor emerita of English at Brown and the lead organizer of the University’s “First Folio! The Book That Gave Us Shakespeare” exhibit, a national tour of a rare, valuable copy of Shakespeare’s First Folio, a tome that includes some of his most famous works including “Macbeth” and “Twelfth Night.”

Shakespeare in the community

Far more than a simple display of a cultural gem, the First Folio exhibit is about engaging the public and demonstrating Shakespeare’s enduring relevance — in fact, an emphasis on outreach to teachers, students, families and the community was a primary factor in Brown’s selection as host to the exhibition, according to the organizer.

“The First Folio exhibit is not a campus event,” Kahn said. “It is for everyone in the state and the region. A program like ¡Shakespeare para todos! tries to bridge the distance between campus and the community. We are saying: ‘This can be your Shakespeare, too.’”

Shakespeare, Kahn said, was a popular writer in his day, and theatergoers had both practical access to his works — the cheapest tickets cost one penny — and philosophical access, because his subjects, from class division, war, power, love and the role of family, are universal. The seeds of ¡Shakespeare para todos! were planted during a conversation in 2015 with Laura Bass, associate professor of Hispanic studies at Brown, about how 40 percent of Providence residents speak Spanish.

Kahn wanted to show that the Bard’s plays could speak to daily life in Latino communities despite being written 400 years ago in England. She chose “Romeo and Juliet” because of its timeless themes, including the ways parents impose restrictions on the social lives of their children and how civic, political and religious authorities can fail to stop cyclical violence stemming from longstanding feuds like the one between the Montagues and the Capulets.

“From machismo to gang culture, to the towering figures of the parents, this is a text about negotiating heritage,” said Felipe Martinez-Pinzon, assistant professor of Hispanic studies at Brown, who is advising the middle school program. “‘Romeo and Juliet’ is a very good entry point to many cultural problems relevant to the Latino community.”

To help the middle-school students crack the text, Kahn, Martinez-Pinzon and Jill Kuhnheim, visiting professor of Hispanic studies, carefully selected a Spanish translation of the play, and Kahn gave the volunteers a lecture and teaching tips. The group decided early on that the students would be encouraged to discuss the play in Spanish, English and Spanglish — a hybrid of the two languages.

Formalizing the middle schoolers’ study of Spanish, a language that for many has an emotional and familial connection, Martinez-Pinzon said, can be empowering.

“They get to see the words in Spanish and in English and make it their own, to own the text,” he said. And embracing Spanglish allows the students to explore a nuanced way of expressing Spanish in the U.S. while doubling the resources for encountering Shakespeare’s rich, demanding text, which includes words that are not commonly used in the everyday speech of English or Spanish speakers.

Ian Russell, a doctoral candidate in Hispanic studies who is currently immersed in leading his second eight-week session of ¡Shakespeare para todos! at Sophia Academy, said students he worked with earlier this spring relied on some English words during a Spanish writing exercise that required them to describe the fairy, Queen Mab, from the play.

Mapping the city

In developing ¡Shakespeare para todos!, Martinez-Pinzon created a map of Providence for the Brown volunteers, indicating how Latinos had settled into the city over the past half century. He asked the volunteers to consider whether a second-generation Dominican sixth-grade student might appropriate the play differently than a more recent immigrant from Colombia.

For Berta Garcia Faet, a doctoral candidate in Hispanic studies and a native of Spain who volunteers with students at the Leviton Dual Language School, the desire to work with ¡Shakespeare para todos! arose from both her drive to share her scholarly knowledge and her sense of solidarity with Latino populations in the U.S.

“Not everybody (or almost anybody) has the chance to have the kind of wonderful ‘job’ I have — researching Hispanic poetry, enriching myself,” Faet wrote in an email. “I’m very much politically conscious of the Latino struggle for recognition and opportunities in the U.S… I’m very happy to work with kids who are part of the Latino community… I’m learning immensely with these students.”

Learning through performing

Kuhnheim, who has written about poetry in performance as a way to expand the potential meanings of a text as well as the audience for it, said the book “A Reason to Read” helped shape the approach the Brown student volunteers took at the middle schools. That book, written by Eileen Landay, former professor of English at Brown, and Kurt Wootton, co-founder of the ArtsLiteracy Project in the University’s education department, is a guide for using performance to get kids interested in reading.

That can range from creating alternative endings to scenes such as the one where Juliet’s father excoriates her for refusing to marry the count he has chosen for her, to composing Facebook posts by the characters in the play, to writing “piropos,” or compliments like the ones Romeo uses to woo Juliet. When Russell asked the girls at Sophia Academy to write a sonnet based on their own lives, they quickly renegotiated and wrote about imaginary lives instead. One student said she was going to write about “a girl who is 12 like me, and her uncle is Martin Luther King. And she goes on marches but she doesn’t know how she feels about them.”

Kahn, who was trained to preserve the text, said she was “doing the opposite of everything I’ve ever done” but that the student response was very positive. “They are totally open, so full of questions, and are so natural and spontaneous,” Kahn said of the middle schoolers.

At Leviton Dual Language School, where sessions are conducted entirely in Spanish, Faet’s students adapted “Romeo y Julieta” to a contemporary Providence setting and wrote three acts with the help of their teacher, Perla McGuinness. Faet said reading Shakespeare has opened conversations about topics like different conceptions of love, gender stereotyping, sexism, machismo and personal freedom vs. the tradition of the group.

They have developed “their own views about all these subjects,” Faet said, which they will share when they perform one of the scenes they created at El Día de los Niños.