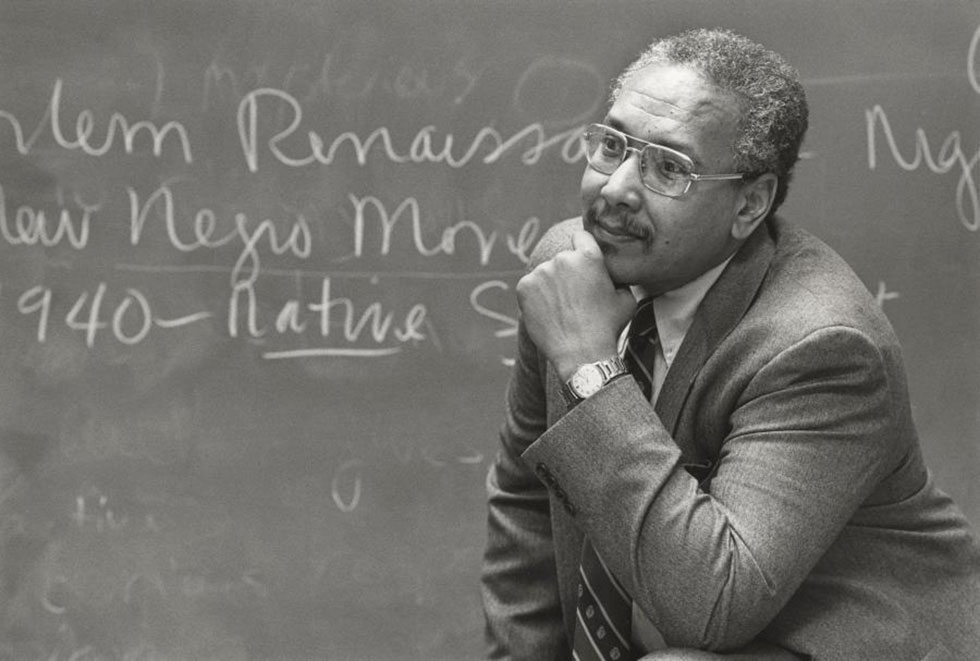

PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — Michael S. Harper, renowned poet and University professor emeritus of literary arts and English at Brown, died on May 7 at age 78.

Harper, who taught at the University from 1970 to 2013, who was Rhode Island’s first poet laureate and published 15 books of poetry over an illustrious career, beginning with “Dear John, Dear Coltrane” in 1970. That volume and 1977’s “Images of Kin” were both nominated for the National Book Award.

From the outset, critics praised Harper’s poetry for its beauty, clarity and expansiveness. A review of “Dear John, Dear Coltrane” in the Virginia Quarterly Review asserted that “Harper’s is a poetry of classically unadorned statement, a direct, unflinching record of a man alive in his time… He creates a language humming with emotion and ennobled by a deeply felt human dignity.”

Harper was much-honored in his lifetime, winning the Poetry Society of America’s (PSA) 1978 Melville Cane Award, the Black Academy of Arts and Letters award for poetry and grants from the National Endowment for the Arts and the Guggenheim Foundation.

In 2008, he was awarded PSA’s highest honor, the Frost Medal for lifetime achievement in American poetry. In bestowing the medal, PSA’s Ruth Kaplan cited his “brilliant, uncompromising and hugely influential poems.”

Gale Nelson, director of Brown’s literary arts program, spoke about the artistry of his longtime colleague:

“Michael Harper’s poetry was built upon strong foundations: he made keen use of the muscularity of bebop jazz and the sensitivity of the blues and the spiritual; he also built on the rigors found in traditional forms of poetry. He blended these traditions with a strong sense of the lyrical and vernacular registers. He dug deep into the history of this nation, celebrating what was beautiful and exposing that which required our attention, our shame, our resolve to overcome. His was a witness to a shared responsibility to overcome the nightmares of our worst impulses, all with an unwavering attention to the sweetness of language itself.”

Harper attended California State University and the University of Iowa Writers’ Workshop, where he was the only student of color in his creative writing classes and lived in segregated housing. That experience, according to Keith D. Leonard, a literary scholar and professor at American University, illustrated “what Harper calls the schizophrenia of this society,” something he explored in his writing.

In “To Cut is to Heal” — a critical companion to Harper’s book “Debridement” edited by Brown alumnus and writer Ben Lerner — Harper said, “In my experience, most history is unwritten, particularly the history about blacks in America, and its traduction is a continuous minefield of delusion and denial, from slavery, to the African slave trade, to ‘Reconstruction,’ and the compromises inherent in the Constitution and the Bill of Rights. So as an American writer you had better have your own sense of history if you are going to be rooted in any kind of truth as you see it.”

While unflinching, Harper’s writing was deeply compassionate. George Cuomo of the San Francisco Examiner and Chronicle wrote that he was “one of the most human and humane” poets, whose work drew “its vitality from the incredible energy of his language and the honesty of his perceptions.”

Harper was equally unstinting in his teaching. In his 43 years at Brown, where he was the first Israel J. Kapstein Professor of English, he was a beloved teacher who taught and mentored generations of students.

“His knowledge was wide and deep,” Nelson said. “His vision was generous, but also honest, tempered by history and an understanding of the human plight.”

The Poetry Foundation has a selection of Michael Harper’s poems here, and more on his life can be found via an online version of a 1997 Brown University Library exhibition in his honor.