PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — In an upstairs studio in the Perry and Marty Granoff Center for the Creative Arts, Brown University sophomore Benjamin Attal stands in stocking feet inside “the Cave,” a cube-shaped interactive virtual-reality environment designed to display 3-D visualizations.

Wearing motion-detecting eyeglasses, he holds a controller in his hand as he leads his classmates, who also don 3-D glasses, past a tree made of words and through a fire in the engine room of a spaceship. Attal has created a narrative world with text objects and graphic design characters known as ASCII art for CAVE Writing, a literary arts course that explores the potential for creating literature in programmable media.

Photo: Nick Dentamaro/Brown University

As the students consider Attal’s work, discussion ranges from technical questions about coding and programming to the nature of narrative immersion. The conversation encompasses concepts from graphic design, film theory, creative writing, computer science and a host of other disciplines.

Without a space like the Cave — and without the Granoff Center in which it is housed — an experience like the one Attal leads would not be possible. And without a deeply held belief in the value created by work that pushes the boundaries of academic disciplines, the space itself might not have been possible.

Chira DelSesto, assistant director of the Creative Arts Council at Brown and point person for Granoff Center programming, said that while arts may be at the heart of the center, the building sticks closely to its mission — to incite collaboration across diverse areas of study at a university that has strategically committed itself to integrated scholarship.

“We are a home not just for creative artists,” she said, “but for creative thinkers.”

Working across disciplines

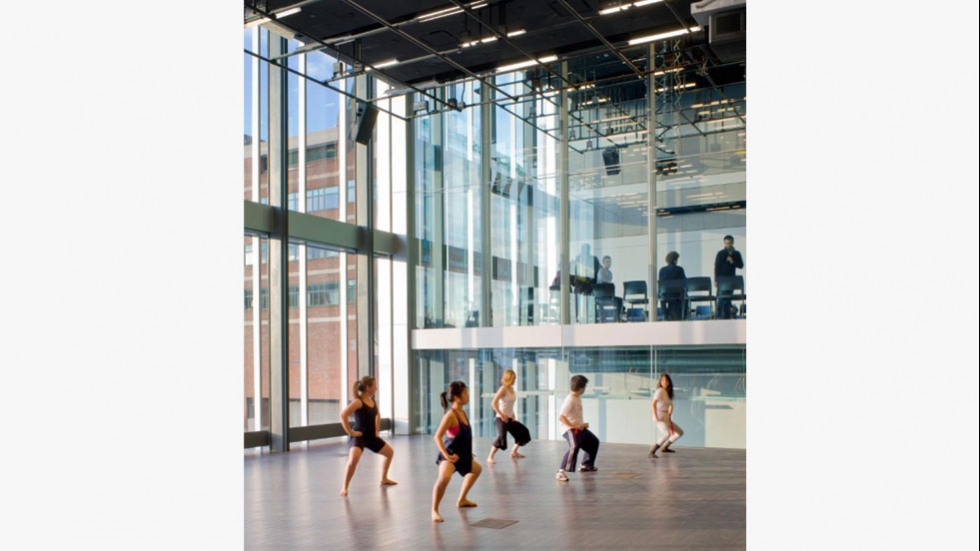

Brown’s commitment to multidisciplinary collaboration and creative thinking expresses itself in many ways across campus, but perhaps nowhere more visibly than at the Granoff Center. Designed by architects Diller Scofidio + Renfro as “a merger” of architectural gesture and instructional methodology, the building opened in 2011. The ability to transcend disciplines was built into the center from the start.

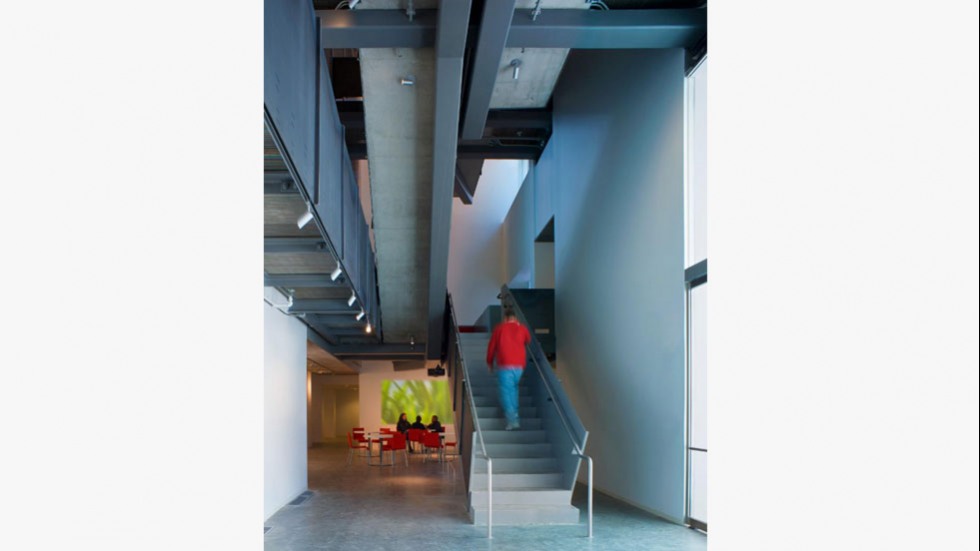

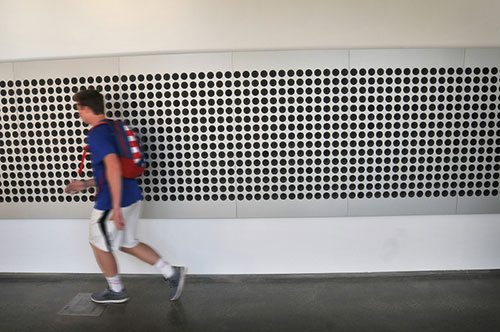

With a western façade made of glass and intentionally misaligned studios and classrooms, bisected by a glass seam so that students in one space can see into other classrooms, the striking building exudes a sense of openness. A central staircase flanked by lounges and exhibit areas encourages the building’s users to repeatedly encounter other people, projects and ideas.

Upon its unveiling, the Granoff Center attracted the attention and admiration of critics, but it also raised questions: Would “collaboration” prove more than mere buzzword? What results would it yield? Could the building itself impact the scholarly practice or artistic expression that took place there?

Photo: Warren Jagger

In the five years since, the Granoff Center has sparked a series of collaborations that stand as tangible answers to those questions.

Neuroscientists, artists and others have teamed up to convey scientific concepts through animations. Artists have worked with biologists and experts in computational modeling to visualize the flight mechanics of bats. Dance students, working with peers in health and human biology, cognitive neuroscience and Middle East studies, have used ethnographic principles to adapt dances for individuals with Parkinson’s disease and autism spectrum disorders.

The center has also become an arts destination, hosting scores of high-profile exhibits by people like influential Chinese artist Cai Guo-Qiang, who makes spectacular works with gunpowder, and Lisa D’Amour, Katie Pearl and Shawn Hall, who used the space for a collaborative interactive installation/theater piece.

Granoff audiences have been treated to lectures by creative thinkers including producer and Brown alumna Christine Vachon, who worked on "Boys Don’t Cry" and "Carol," among other films; Billy Siegenfeld, founder of the groundbreaking JUMP RHYTHM Jazz Project; and Jodie Foster, who spoke to students about her experiences as an actor and director in a visit this spring.

The center has become a campus crossroads and a forum, a place to receive the kind of project that has no single home within a traditional department, faculty and students say. It is a place that encourages scholars to be both/and — both scientist and artist, for example — rather than either/or.

The Brown ethos

That same lack of binary thinking informs Brown’s distinctive open curriculum, which counts as a core tenet the encouragement of “individuality, experimentation and the integration and synthesis of different disciplines.” Those principles, in turn, presented a model for the kind of work that arts faculty envisioned as they developed the concept for what became the Granoff Center.

Richard Fishman — a professor of visual art, director of the Creative Arts Council and a primary driver of the center — locates its origins in a decision by the arts departments to pool budget resources in the early 2000s to create a multimedia lab, which was situated in the Department of Visual Art for general use.

“In conversations about what else we might do,” he said, “that’s when the collaboration idea really took hold.”

The Creative Arts Council, Fishman said, was encouraged by the Creative Arts Advisory Board, founded by Brown parent and trustee emeritus Marty Granoff. The group first proposed an 80,000-square-foot center to house the creative and performing arts and new collaborative projects.

The concept was greeted with support but deemed too expensive. Ruth Simmons, Brown’s president during the center’s development and groundbreaking, directed the council to cut the building’s size and cost in half, suggesting that the faculty “think about core mission and eliminate everything else,” Fishman recalled. That advice had a productive effect, Fishman said, because they had to do away with everything that wasn’t collaborative — the reconceived building had no faculty offices or studios.

“This gave us a place that was a shared opportunity and had to be governed democratically,” Fishman said, “and that is what made it a success. We met every other week to negotiate. We had to get along. The faculty, through their collegial method, their way of working, made it work. We always came to consensus.

“Creativity comes from working up against obstacles and tensions and if you’re able to negotiate that you come up with something fresh and new. If you can’t negotiate it, things collapse.”

The building wouldn’t exist without the commitment of the Brown community. The entire project was funded by donors, led by Perry and Marty Granoff. And, Fishman said, the administration did not abandon the project in 2008: “Brown did not stop us in one of the worst economic downturns in the last 25 years. I’ve always thought of this project as a miracle. It could only happen at Brown because of the culture and history and the ethos of the new curriculum.”

New forms of scholarship

As the Granoff Center approached its opening, Fishman initially went “door-to-door,” he said, to cultivate interest among faculty across the University and at the Rhode Island School of Design in teaching new, interdisciplinary courses. Having piloted a course called “Hybrid Art” in which collaboration and teamwork across disciplines proved essential, he could speak from direct experience.

“Can something new come out of a disagreement? The answer is yes,” Fishman said. “Whatever you can do to make people think differently leads to an enlarged creative process.”

In the years before the 3-D virtual-reality room known as the Yurt came online in 2015, Professor of Computer Science David Laidlaw used the Cave and its technology for his Virtual Reality Design for Science course. Laidlaw said that because “what we were trying to teach is how scientists want to interact with data they don’t understand yet” — like kinematics of human wrists — the course involved intensely thoughtful collaboration between artists and designers and scientists.

He found that students were receptive to the idea of collaboration and were perhaps better at it than faculty “who haven’t practiced collaboration,” he said.

“Students are more plastic,” Laidlaw said. “It’s different each time, with each new cohort of students. Some have more difficulty appreciating the other disciplines, and some have more difficulty questioning the other disciplines.”

When students treat a field of study as dogma or, conversely, with disdain, the class can help pry them out of a set attitude,” he added. “Part of the class is to struggle with that concept. Part of what we have to do in society is learn how to differ.”

Other Granoff-centered courses aim to harness the communicative value of the creative arts to promote the understanding of other disciplines — science concentrators building animation and scriptwriting skills, for example, or Portuguese and Brazilian studies scholars examining how visual, literary and performing arts can build cultural awareness while aiding language acquisition.

John Stein, senior lecturer in neuroscience, has taught “Communicating Science Through Visual Media” with Steven Subotnick, animator and RISD critic in film, animation and video, for four years. Teams of students develop videos that explain, for example, what genetically modified organisms are and how they are made. Stein and Subotnick carefully balance and distribute tasks in creating the animations, creating a rich classroom experience that avoids the re-creation of traditional departmental silos.

Zoe Greenberg, who said that as a teaching assistant for introductory chemistry classes she felt limited using just a chalk and chalkboard, took the course to expand her tools for teaching.

“Working with RISD students was fantastic,” Greenberg said, “because they have a very different perspective from me, a concentrator in the physical sciences. When I was writing the script for our video, they were able to help me edit and refine my writing so that it could be accessible to a wide variety of audiences.”

Casey Dunn, an associate professor of biology, works in the Granoff Center with students across the disciplines to create animations that focus on a single animal or organism, such as a fried egg jellyfish, for a collaborative online platform called CreatureCast.

“A lack of fluency with a subject or discipline can sometimes lead to really new and distinct ideas when collaborating,” Dunn said. “When someone comes from a different field, they often have this hyper-focus and double-down as they soak it all in.”

DelSesto, who oversees grants, programming and course scheduling from her office in the Granoff Center, has seen firsthand how the building and its programs encourage both the practice and theory of collaboration.

“It encourages you to explore what collaboration really means,” DelSesto said. “How do two people working in the same medium work on one project? What happens when they are based in different disciplines and have to bring those differing media, tools, languages and assumptions to a joint project?”

Often, she added, these collaborations lead to “prototypical late night college discussions about ‘what is art?’”

The layout of the building itself can answer some questions about what art can be.

Photo: Frank Mullin/Brown University

Julie Strandberg, senior lecturer in theatre arts and performance studies, takes over the entire center every year for the American Dance Legacy Initiative’s Mini-Fest, using the building as a site-specific installation. Pedestrians on Angell Street can happen upon the dance performances just by looking up, and Strandberg can capture the feel of dances that were made to be performed in nontraditional theater spaces.

“It allows for a unified larger theme — an installation that can make use of multiple perspectives and present big ideas about dance,” Strandberg said.

Looking forward

In looking toward the Granoff Center’s future, Fishman finds a potential analogy in the success of the open curriculum. “Forty years later, it’s still doing now what it set out to do,” he said. This makes him hopeful about the prospect of the Granoff Center continuing to fulfill its mission over the long term.

“The success of this building, its courses and its mission was followed by lots of other schools,” Fishman said. “They visit and ask, ‘How did we do it and why did it work?’ The building wouldn’t do much without the spirit that created it.”

Fishman visits other institutions where buildings with similar aspirations have failed to meet their charge. What’s different about Brown, he said, is that “the building’s design and the leadership and the administration work together. It’s nothing you can take for granted,” and it “has to be nurtured continuously.”

The future of the center, Fishman said, “was always predicated on change. Nothing is sacrosanct — there are always questions and a constant cycle of searching for the new,” he says, but the Granoff bears out what he and others suspected was true a decade and a half ago: “Good ideas can be catalysts for institutional change.”

Granoff Center: 5 Years of Creativity from BrownCAC on Vimeo