PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — On July 2, Mark Steinbach, Brown University's organist and curator of instruments, sat at the famed “great organ” at the Cathédrale Notre-Dame de Paris and gave a performance that included two world premieres of compositions by Eric Nathan and Lu Wang, both assistant professors of music at Brown.

“Performing at Notre Dame was a magical experience I will not soon forget,” said Steinbach, who is also a lecturer in music.

Photo: Courtesy Mark Steinbach

To give a concert on the organ as a guest is an honor. Visiting musicians are selected by the cathedral’s tenured organists through a competitive process, and performances may be scheduled several years in advance.

It is also a challenge.

Organs, especially historic ones, are not standardized instruments, Steinbach said, and the number of keyboards and stops — devices that control the flow of air to sets of pipes and determine the sound the instrument will make — vary widely. The great organ is a large and complicated instrument, with five keyboards and 8,000 pipes, some of which date back to the 1400s, Steinbach said.

Making the soaring architecture and stained glass feel a bit more homey was a cohort of Brown faculty and alumni in the audience, including a group from the Brown Club in France as well as Nathan and Wang. Wang made the trip from her artist residency at Civitella Ranieri in Italy.

When planning his performance at Notre Dame, Steinbach said he had to think about the acoustics of the cathedral and the types of works that would take advantage of the sound quality of the great organ, which he described as “romantic, with some divisions that may sound more baroque.”

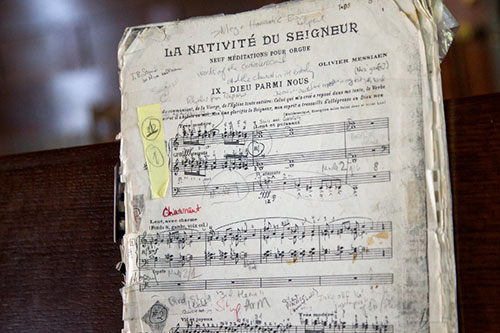

“The organ, like the cathedral itself, contains many layers of history,” Steinbach said. He noted that the instrument had been played by Olivier Messiaen, the 20th century modernist French composer and organist, and César-Auguste Franck, the 19th century French-Belgian composer whom Steinbach describes as “the granddaddy of French romantic music." Steinbach played their pieces to open and close his performance.

“Performing works of Messiaen and Franck on a pipe organ which both had played was amazing,” Steinbach said. From Messiaen, Steinbach moved into American composer Philip Glass’s “Mad Rush,” a piece that he said works well in a large space like the cathedral.

Photo: Nick Dentamaro/Brown University

“In Notre Dame, there are a lot of seconds of reverberation… so it’s really different from playing in a small chamber hall. There’s this big wash of sound, so not everything works.”

Steinbach then premiered Nathan’s “Immeasurable” and Wang’s “Missing Absence,” which Steinbach commissioned for his concert at Notre Dame and will play on his stops at venues in Germany throughout July. He will also play the works at Brown’s Sayles Hall on October 1.

While the commissioned works were the first Nathan and Wang had created for the organ, neither composer flinched at the challenge.

“When Mark asked me to write a piece for him I immediately said yes, although I have never written for organ before,” Wang said. “Even only being his colleague for a short period of time in the music department, I’ve been very impressed by his great musicality and virtuosity at live performances.”

Wang said she and Steinbach “tried my sketches many times and explored possibilities on the settings of stops. The experience of working with Mark has been absolutely rewarding and fun.”

Steinbach was delighted with Wang’s piece, which he called very beautiful and singular.

Nathan experimented on the organ in Sayles Hall as he learned to compose for the instrument and was excited by the prospect of having the piece played on historic organs at Notre Dame and, later, at Steinbach’s stop at Nikolaikirche in Berlin.

“Many of the ideas in my piece arose from the physical act of improvising on the organ and finding what new textures I could create from the wealth of possibilities the instrument offers,” Nathan said.

“Immeasurable” embraces “organs, the large physical spaces they inhabit, and how the instrument’s own mechanics create a sense of space and distance,” Nathan said. He dedicated the work “to Paris and its people, in the aftermath of the terrorist attacks of 2015.”

Steinbach said “Immeasurable” is “incredibly complex and amazing. As Eric said, he likes to challenge what’s possible. He likes to push the boundaries of what anyone has ever done for an instrument before.”

Photo: Nick Dentamaro/Brown University

To play complex new pieces on an unfamiliar organ like Notre Dame’s, which has two more keyboards than the Hutchings-Votey organ at Sayles Hall that organ Steinbach plays most regularly, involves a steep learning curve.

“On a piano you have keys and a sustain pedal, but with an organ you have parts” like stops, knobs and pistons that are in different places on different instruments, Steinbach explained.

At Notre Dame, “they have a person there who helps you with the stops while you’re practicing and while you’re playing,” Steinbach said. “That’s how big of an operation it is. Generally, an organist presets pistons, or buttons, and that’s how you decide how it will sound.”

At Notre Dame, Steinbach was able to set pistons in advance of his concert, but he knew he would have to master the great organ’s configuration and become comfortable working with the assistant in just two practice sessions, a burden he carried lightly.

“You need to have good muscle memory as an organist,” Steinbach said, adding “I need to do more yoga.”

Steinbach will give concerts at five sites in Germany during the month of July, concluding with a performance at Handel and W.F. Bach’s former church, Marktkirche in Halle, on July 29.