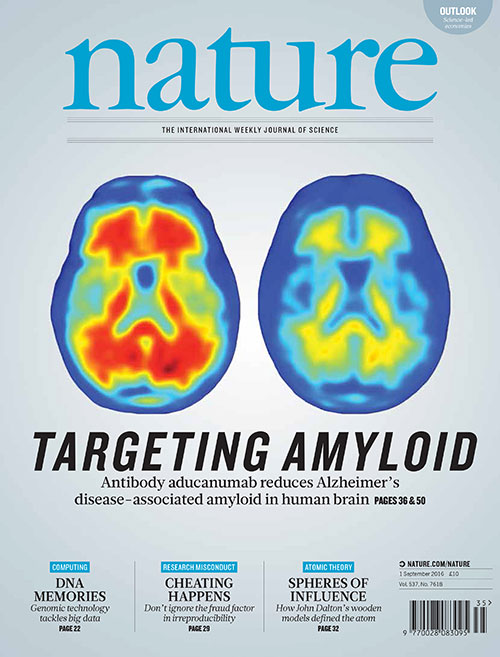

PET brain scans on the cover of <em>Nature</em> show the before and after of a patient who received the top dose of an anti-Alzheimers drug in a newly reported clinical trial. Red, conspicuously missing in the after image on the right, depicts harmful plaques. Sevigny, et. al., Nature

PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — Dr. Stephen Salloway has been working to defeat Alzheimer’s disease for decades. This week, he is a co-author on a study featured on the cover of Nature showing what he calls “the most promising treatment results in my 25 years at Brown conducting research on Alzheimer’s disease.”

Salloway, professor of neurology and psychiatry in the Warren Alpert Medical School and director of Neurology and the Memory and Aging program at Butler Hospital, helped to lead the clinical recruitment and imaging for the trial of a Biogen drug called aducanumab. The antibody helps brain cells resist the plaques of amyloid beta proteins, which build up in the disease.

Salloway discusses the trial results and what they mean below.

What were the main findings of the study, and how encouraged are you by what you found?

The human antibody aducanumab substantially lowered amyloid plaques and appeared to slow cognitive decline. The amyloid lowering and cognitive effects were more pronounced at higher doses. These results bring new hope to patients and families dealing with or at risk for Alzheimer’s disease.

What part did researchers in Rhode Island play in this study? How did Brown, Butler and Rhode Island Hospital attain such an important role?

The Brown-affiliated memory research programs at Butler and Rhode Island hospitals were among the top recruiting sites for the phase 1b trial. The amyloid PET scans, the primary outcome measure for the trial, were performed at Rhode Island Hospital, while advanced MRI imaging was performed at the MRI Research Facility on the Brown campus. I was the first to report the development of amyloid-related imaging abnormalities (ARIA), the main side-effect of anti-amyloid antibodies, and I have extensive experience training investigators to detect and manage ARIA. Safely managing ARIA is critical to achieve optimal therapeutic dosing.

"The goal is right drug, right dose, right patient with a focus on prevention and early intervention."

How does aducanumab work?

Aducanumab was developed using a novel technique developed by Neurimmune called Reverse Translational Medicine (RTM), involving extensive antibody screening in a pool of “healthy agers” to identify antibodies that confer resistance against proteins, such as amyloid and tau, which aggregate in neurodegenerative disorders. Aducanumab, which targets the N-terminus of ABeta 42, was cloned as the lead anti-amyloid molecule for clinical development. If this strategy is successful, RTM may be used to identify antibodies to treat other neurodegenerative disorders, such as Parkinson’s disease.

Why do you think this trial turned out so well when other amyloid-targeting medications haven’t fared as successfully?

We don’t know for sure. The unique properties of this human antibody derived from healthy agers may be one factor. For example, aducanumab penetrates the blood-brain barrier, preferentially binds to toxic forms of Abeta, and activates microglia to clear plaques. Aducanumab may hit a key target of the amyloid molecule at the right doses, and the doses used in other trials may have been too low.

What’s next for this effort?

Two global phase 3 confirmatory trials are actively recruiting and will hopefully lead to FDA approval. Dose adjustments and a slower titration schedule have been implemented to reduce the frequency and severity of ARIA. The Butler Memory and Aging Program and Brown are global leaders in the phase 3 program. The phase 1b aducanumab data are the most promising treatment results in my 25 years at Brown conducting research on Alzheimer’s disease and move us closer to meeting the U.S. National Plan to find treatment breakthroughs for Alzheimer’s by 2025. The goal is right drug, right dose, right patient with a focus on prevention and early intervention.