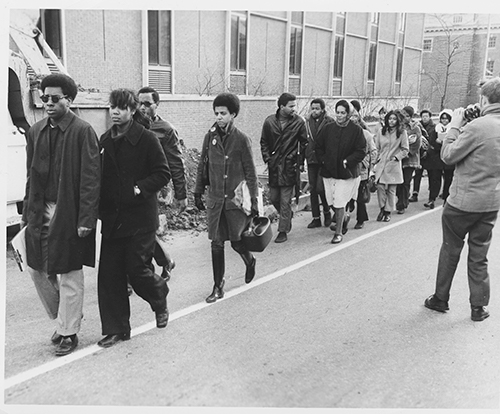

PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — The trailblazing 1968 walkout of black students who demanded an increase in the enrollment of students of color. The creation of foundational programs such as Rites and Reason Theatre, the Third World Transition Program and the Minority Peer Counseling Program. The recent recognition of Indigenous People’s Day on campus.

The Brown Center for Students of Color (BCSC) and its precursor organizations have been at the center of all of these defining Brown moments — and many more. This year, the Brown community cornerstone, known until 2014 as the Third World Center, celebrated its 40th anniversary. Asked to pinpoint the most meaningful among these moments, current BCSC director Joshua Segui said that it’s impossible to pick just one.

“There are historical moments that stand out, but it’s important to remember that each one represents a culmination — a set of collaborations and conflicts that were shaped by and in turn shaped a particular period,” Segui said.

Despite the impossibility of the task, 12 individuals — from students and alumni to faculty and staff — who have been closely affiliated with BSCS and its precursor organizations over the years offered reflections on one defining historical moment for students of color at Brown.

Collectively, though certainly not exhaustively, their answers provide a sense of the accumulation of moments that Segui cited. They also illuminate the central role that students of color have played in visualizing, vocalizing and mobilizing to make Brown a more equitable and inclusive campus.

John M. Robinson, Class of 1967

Dean of student life; associate dean of the College; associate director of admission (1973 – 1991)

While a student at Brown: Co-founder of the Afro-American Society of Brown University

“On a dreary February night in 1967, Bill Poole, Anderson Kurt and I — all black — found ourselves by chance in the Rockefeller Library’s second-level anteroom outside the reserved reading room. In our conversation, we all registered a higher-than-normal level of boredom, fatigue and depression. We decided that if we could get our fellow black students into the same room at the same time, we might at least improve our mood, perhaps plan a party or a field trip — something, anything to make things better.

“There were about 20 of us on campus. Only four men in my class remained at Brown of the eight who began in 1963. There were no black staff, faculty or counselors. We were invisible, unnoticed and uncared-for. With no emails or cell phones, we resolved to tell any brothers or sisters we encountered to meet in my apartment on Hope Street two nights hence. And we did.

“And when about 12 of us gathered, almost clandestinely, magic happened. Without words, we began to feel our corporate strength, our connection, our village. The circle expanded week by week to form the Afro-American Society of Brown University — the AASBU. The formation of AASBU led to the '68 walkout, led by the black Pembroke women. AASBU renamed itself the less-polite Organization of United African People. Ultimately, that was a prelude to the ’75 University Hall takeover, the resignation of President Don Hornig, the negotiation which founded the first Third World Center and the reinstatement of the Third World Transition Program.”

Robert G. Lee, Class of 1980 (Ph.D.)

Director of the Third World Center (1981 – 1985); associate dean of the College and associate director of the Center for the Study of Race and Ethnicity in America (1985 – 1990); associate professor of American Studies (1990 – present)

“The walkout of black women of Pembroke College and black men of Brown in 1968 articulated the issues of racial justice at Brown in admissions, faculty representation and student support that still define the struggle today. The courage of those students has served as an inspiration to generations of students of color and their allies for the past half-century.”

John Eng-Wong, Class of 1962

Admission officer (1972 – 1977); assistant dean of students (1977 – 1980); director of the Office of Foreign Student, Faculty and Staff Services (1980 – 2005); executive officer of the Council on International Studies (1980 – 1985); visiting scholar in American Studies (2005 – present); special adviser American Studies (2011 – 2017)

“The formation of the Asian American Students Association, born in the late ’60s, against the backdrop of the Vietnam War and civil rights activities nationwide, crystallized the self-image of Asian Americans as people of color and as a part of the rainbow. The Third World Center became the spawning ground for newly inclusive communities, and the center’s activities promoted coalition building.

“For myself, I was witness to a sizable increase in Asian and Asian American enrollments and happy for that increase, but also increasingly aware that cross-cultural awareness needed enhancements if these students were to reach their full potentials. As one of a collective of Asian American staff and faculty, we worked to build capacity.

“Over the perspective of more than four decades, I am pleased by the trajectory. Students of color at Brown today have inherited a place made better by the work of generations past. New generations are likely to face new challenges; I hope they will be unafraid to find better solutions than the ones available before.”

Sayantani DasGupta, Class of 1992

While a student at Brown: Minority peer counselor and Third World Center librarian

“For me, one of the most important, and personally impactful moments in Brown's history for students of color was the formation of the Third World Transition Program (TWTP) in 1975 — originally begun as the Transitional Summer Program in 1969. TWTP was a foundational experience in my Brown tenure. It was literally the first real taste of college I got, and as such, it was the wakening ground for my already established activist consciousness. At TWTP, we students of color found a sense of community in each other but also gained the critical thinking skills to think and speak about racial, economic, gender and other issues of justice. TWTP gave me a safe, nurturing but challenging space to begin using the activist voice that would grow louder and more confident over my years at Brown. I am not overstating it to say that the skills and passions I gained at TWTP have stayed with me for a lifetime.”

Mee Moua, Class of 1992

While a student at Brown: Asian American Student Association officer

“During my time at Brown from 1988 to 1992, two significant events took place, which laid the foundation for some of the cultural and structural changes at Brown today. The first was the movement for need-blind admissions. The other was a review and re-issuance of the Blue Ribbon Committee report on diversity and racial equity. I was very much a part of both of these efforts. I am very excited to see that, even 25 years later, Brown continues the commitment to make the University accessible to all students and is leading the charge to advance truth, racial healing and transformation within Brown and among legacy institutions made possible by a history of enslavement and oppression.”

Joshua Segui

Director of the Brown Center for Students of Color (2016 - present)

“I'd like to name the hiring of Anne Marie Ponte as one of the most important moments in Brown's history for the University’s students of color. She has a communal mindset and is deeply empathetic and incredibly hardworking. Formally, her role has changed over time. Informally, she is and has always been the place to go when times get tough. Whether planning a major conference or experiencing a personal conflict, students know they can turn to Anne Marie. As she often says, ‘If I can't help you, I will find someone who can.’ Anne Marie has served at the BCSC for nearly half its existence and has been an unwavering champion for students of color. She’s the one on the ground on all the days that aren’t remembered.”

Sheryl Brissett Chapman, Class of 1971

While a student at Brown: Leader of the 1968 black student walkout; co-founder of Rites and Reason Theatre

“The first African American president of Brown, Dr. Ruth Simmons, confronted the underpinnings of anti-black racism and the toxic residuals of slavery at Brown and beyond by promoting provocative research and ensuring that difficult moral discourse occurred on campus. Through her sheer leadership and passion, she altered an institutional culture steeped in denial and misinformation, while challenging black alumni to claim Brown and invest in future generations. Brown has become the forerunner and a model for elite universities across the nation, as they grapple with historical inequity and economic exploitation.”

Xochitl Gonzalez, Class of 1999

While a student at Brown: Minority peer counselor; Latino history month coordinator; TWTP coordinator; first Latina senior class president

“When I was at Brown, we established the ethnic studies concentration. I say ‘we’ because it was the cumulative result of us coming together as a community to insist that our stories, too, belonged in academia. But the thing that moved the needle the most, I think, was establishing need-blind admissions and increasing aid packages in the early aughts. It’s hard to imagine that there was a time when we weighted monetary need in the admissions process and often were not able to meet financial needs of students who were admitted. This had a huge impact on students of color, not only in acceptances, but also in their matriculations and lifestyle while at school. Not every student of color had to work 10, 20 or even 30 hours a week and opt out of meal plan to save money anymore. It changed the dynamic and possibility of what it meant to be a student of color at Brown. And I think it also illustrated to the University the places where we could do better — that meeting need extends past tuition. I think that the diversity and inclusion action plan has already started to deal with that even more holistically.”

Brickson Diamond, Class of 1993

While a student at Brown: African American history month coordinator; board member of the Brown Organization of United African People

“The 2003 to 2006 work of the Steering Committee on Slavery and Justice, their report and the resulting discussion marked the most important moment in Brown's history for the University's students of color and the University itself. The committee, which included faculty members, undergraduate and graduate students, and administrators, was charged to investigate and to prepare a report about the University’s historical relationship to slavery and the transatlantic slave trade. Facing this difficult history and creating a space for examining its implications in academic and community contexts set a standard and a permanent lens through which we can understand and challenge all that is Brown and America.”

Atiba Mbiwan, Class of 1982

While a student at Brown: Editor of the African Sun, newsletter for and about the black community at Brown

“Historical moments define our identity, and the creation and naming of the Third World Center at Brown was pivotal for students of African, Asian and Latin American descent, as well as the native people of North America and other colonized lands. But time moves forward. Recognizing that the notion of a ‘third world’ was obsolete in the rapidly evolving global community of the 21st century, a new name — the Brown Center for Students of Color — was chosen for this historical moment. My Brown experience led me to also change my name after a study abroad experience in Nigeria. This reinvention through renaming is vital to learning and serving for both individuals and institutions.”

Felipe Floresca, Class of 1973

Director of the Third World Center (1978 – 1980)

While a student at Brown: Cultural director of UMOJA (Black Student Union); member of the Brown Committee to End the Vietnam War

“On Feb. 1, 2016, Brown President Christina Paxson released Pathways to Diversity & Inclusion. This blueprint for university diversity and inclusion represents the embodiment of almost 50 years of student activism. Pathways is a commitment by the University to pave a path forward grounded in the architecture of change and not window dressing.”

Kara Roanhorse and Sierra Edd, Class of 2018

Former Native American Heritage Series programmers

“The renaming of Fall Weekend to Indigenous People's Day was a success in large part to Native Americans at Brown's initial leadership to fuel and strengthen the student movement, notably from 2009 to 2016. The labor, resistance and resilience of Native-Indigenous students, past and present, resulted in an outstanding example of critical solidarity and fostering engagement by students to establish both a day of recognition and dialogue to discuss historical and ongoing Native-Indigenous issues on Brown's campus. Our call to action was heard and met, not only by our peer student groups, but also by members of the staff, faculty and administration. There would not have been a renaming without the statements of support written by the Black Student Union, the collective of Asian/Asian American and Pacific Islander students, the collective of Latinx and Latin-American students, and the collective of Multiracial and Biracial students. This experience has truly demonstrated how we stand on the shoulders of many. Our hope going forward is that we remember this time and continue to fight for justice together in solidarity.”

Nour Asfour, Class of 2018

SWANA Heritage Series programmer

“In my past two years at Brown, I have had the honor of working with the BCSC to create an inclusive space for students who identify as Southwest Asian and North African, or SWANA. During the 2015-16 academic year, SWANA students began lobbying for recognition and greater representation from Brown. Due to the efforts of SWANA students and other dedicated students of color, the BCSC created a SWANA Heritage Series in 2016. In an act of true solidarity, programmers from the other heritage series voted and agreed to take a pay cut and split their budgets in order to create the new heritage series. Serving as the first SWANA Heritage Series programmer, I worked with Anne Marie Ponte, the coordinator of co-curricular initiatives, to put together meaningful events that center the cultural, political and racialized experiences of SWANA students. The series has been very successful in its pilot year and will grow to have two co-programmers in the upcoming year.”