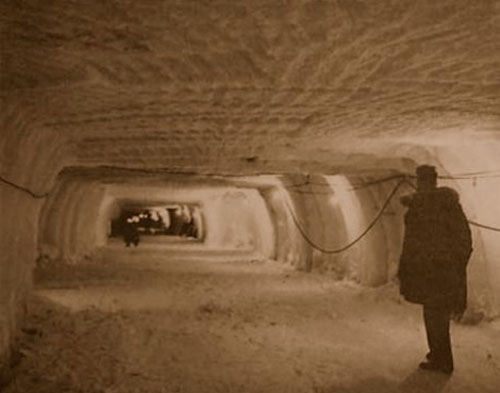

PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — Greenland’s vast ice sheet has long been home to Project Iceworm, an abandoned Cold War-era U.S. Army initiative designed to deploy ballistic missiles with nuclear warheads against the Soviet Union. When the project was shuttered in 1967, military planners expected that any materials left on site would be safely frozen in ice and snow in perpetuity.

Now, melting ice in a changing Arctic has remobilized some toxic waste at one Project Iceworm site and threatens to do the same at other project sites. The consequences, a new study finds, could extend far beyond those to the environment — creating unexpected cleanup costs or costs for compensating local inhabitants affected by environmental problems as well as political and diplomatic conflict between the U.S. and countries hosting the bases. Environmental problems at U.S. bases can also cause political conflict between the U.S. and countries neighboring base-hosting countries if toxic wastes migrate beyond the boundaries of the host country. Contestation over responsibility for such costs at the Project Iceworm sites has already led to the ouster of Greenland’s foreign minister.

Jeff D. Colgan, an associate professor of political science and international studies at Brown University, details the consequences of Project Iceworm in a new study published in Global Environmental Politics. Lessons learned from this case, he says, can create a framework for understanding the political, diplomatic and financial impact of environmental problems at U.S. military bases.

“This case could be the canary in the coal mine for future environmental politics surrounding military bases,” Colgan said.

Colgan used Project Iceworm as a case study for understanding the likely political fallout from what he calls “knock-on effects” of climate change. Those effects are secondary environmental problems — such as damage to infrastructure or the release of chemicals or waste — that can manifest when temperatures and sea levels rise.

Project Iceworm was a particularly useful site to study in considering the impact of climate change on military bases, Colgan says, because climate change has dramatically affected weather patterns in Greenland. In addition, the areas immediately surrounding the project’s sites are uninhabited, so the causal effect of climate change can be isolated from other factors and forecast with relatively high scientific certainty, he said.

The main environmental problem at Project Iceworm is the release of toxic polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs). There is also diesel fuel and a reportedly small volume of low-level radioactive waste at the sites, according to Colgan.

“If remobilized, PCBs from the four sites would likely bioaccumulate within the marine ecosystem in this region,” Colgan wrote.

The PCBs could cross national boundaries, impacting populations in Greenland and Canada, and potentially put personnel at the U.S. Air Force’s Thule Air Base at risk, according to the study.

Thus, the political fallout of remobilized PCBs could entangle the U.S. and Denmark — the countries that signed the original treaty allowing the bases to operate — Greenland, now a semi-sovereign territory of Denmark, and Canada, whose waters and fishing areas might be affected.

A complicating issue is that at the time the 1951 Defense of Greenland Agreement establishing the bases was signed, Denmark “had a nominally nuclear-free foreign policy,” Colgan wrote in the study.

That matters because the treaty allowed the U.S. to remove property from the bases or dispose of it in Greenland after consultation with Danish authorities. But “Denmark could argue that it was not fully consulted regarding the decommissioning of certain abandoned military sites, and thus any abandoned waste there remains a U.S. responsibility,” Colgan wrote, adding “the Danish government, let alone its electorate, was never officially approached with a request or plan to deploy nuclear missiles to Greenland.”

While the specific communications between the U.S. and Denmark suggest that Danish authorities may not have wished to be fully briefed about the activities at the site, as Colgan describes in the study, the legal and historical context provides a means of contesting treaty agreements allowing the U.S. to leave waste at the bases.

The effects of climate change on overseas and domestic military bases

The possible exposure and mobilization of toxic materials due to rising temperatures demonstrates how climate change’s unanticipated effects can destabilize both the operating or decommissioning plans established for military bases and the political orders under which they operate, Colgan said.

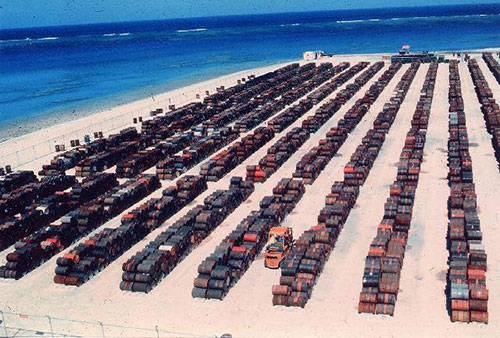

But environmental effects at military bases are not restricted to locations that depend on ice for containment of toxic wastes. In addition to changes in precipitation and storm patterns that affect bases worldwide differently, rising seas are a serious concern at low-lying bases that house toxic waste.

“The rising sea levels associated with climate change elevate the risk that toxic materials left on low-lying coral islands will be remobilized into the ocean,” Colgan said.

During the Cold War, the U.S. military left radioactive waste at the Johnston Atoll and the Marshall Islands, the study notes. Toxic materials were also left in Guam, Micronesia, the Solomon Islands and Midway Island, Colgan wrote.

“Other countries, especially those located in the Pacific, could object strongly,” Colgan asserted.

This has both scholarly and policy significance.

“The United States alone has hundreds of overseas bases that require continuous political coordination with host governments,” he said. “Climate-related environmental hazards could represent a new kind of tension within international political alliances.”

Conflict could also occur between the U.S. government and the residents of host countries who are directly affected by base operations, according to the study. Additionally, environmental problems could generate political tensions between groups within the same country who are affected differently.

Domestically, Colgan said, there are concerns that rising sea levels could submerge long quays that destroyers or cruisers use to dock, like those at the base in Norfolk, Virginia.

Of the U.S. military’s response to the threat unforeseen environmental problems present to political and diplomatic stability, Colgan said, “The military is very good at managing directly anticipated problems, but it’s not as good at handling complex interactions that arise from unanticipated effects.”

Colgan noted, however, that the federal General Accountability Office recently released a report saying that the military is not doing enough to address the problems climate change is expected to cause at military bases.

“I hope this study will give the military and policymakers an extra nudge to think more carefully about the complicated politics that come with overseas military bases in a world of climate change,” Colgan said. “Outside of the military, I think policymakers in Congress and elsewhere ought to see this study as one more example of the dangers of climate change, and be additionally motivated to mitigate the risks of climate change.”