PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] —The National Endowment for the Humanities has awarded Matthew Rutz, an associate professor of Egyptology and Assyriology at Brown, a $166,632 grant to digitally preserve clay tablets that are important to Syria’s cultural heritage. The project, co-directed by Jacob Lauinger of The Johns Hopkins University, will enable researchers to explore the country’s ancient history and provide critical new tools for understanding the writing on the tablets.

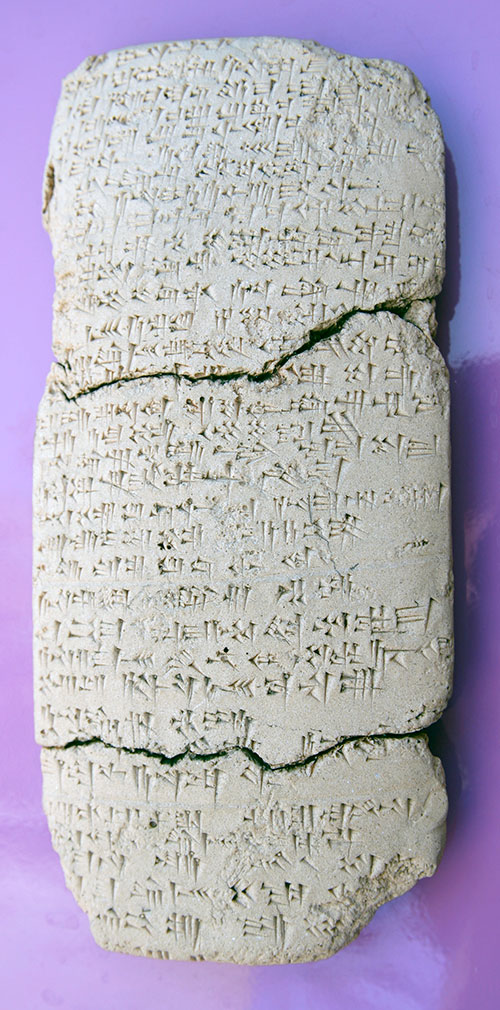

The digital preservation project will bring together into a searchable database the texts of thousands of clay tablets, inscribed in cuneiform script, that document the political, social and economic life of Ugarit, a cosmopolitan city that flourished more than 3,000 years ago.

Rutz and Lauinger will translate into English 1,887 cuneiform texts from Ugarit and make them available in a single online resource, greatly enhancing scholarly and public access to the texts. The researchers will work from published images of the tablets, given that the physical tablets reside in scattered locations in Syria.

“These are ancient, historically unique documents that are imperiled by modern-day conflict in Syria,” Rutz said.

The war in Syria brought a halt to archaeological excavations in the country in 2011, and cultural heritage sites, particularly in Aleppo, have been prone to damage, Rutz said. Tablets that were housed in Syrian museums have been difficult to track since — some have been looted and others have been moved by curators seeking to protect them. A pilot project nearing completion by Rutz and Lauinger has created a digital record that investigators can use to determine whether a tablet resides in its assigned museum or has been moved or lost.

The project funded by the new grant will focus less on control of the artifacts and more on increasing access to the texts and enhancing the type of research scholars can perform. In addition to translating the archival texts, Rutz, Lauinger and a team of graduate students will transcribe the cuneiform script into the Roman alphabet as part of an international research collaborative, the Open Richly Annotated Cuneiform Corpus.

The effort will contribute to a burgeoning digital infrastructure in a field that has traditionally focused on print publication, Rutz said, uniting a large set of texts that are now documented in dispersed publications, many of which are out of print. The translations will make many of the tablets available to English speakers for the first time, and the digital format will allow scholars to use digital humanities tools like data mining and visualization.

“This will allow us to process this material better and to ask synthetic questions about it — from querying spelling habits, to mapping social networks, to addressing questions about agency in ancient economies — rather than worrying about just translating individual tablets,” Rutz said.

The texts on the tablets range from treaties and legal contracts to state records and personal letters, providing an opportunity to research all echelons of social life in the Late Bronze Age (c. 1350 to 1185 B.C.) in Ugarit, Rutz said.

“The political history is known well in its general outlines, but we’d like to tease out what social life and economic relationships looked like on different scales,” Rutz said. Prior research, he said, has given a “taste of what the end of this flourishing period looked like. We have a chance to learn about some of the people who are largely absent from historical record, like a debt slave, and how that person integrated into other social structures, like the family.”

The digital resource will also allow scholars to navigate the complexities of decoding the ancient languages that were transmitted by an imported technology — writing — in its various forms, or scripts.

“Most native English speakers for whom the predominant script is alphabetic have trouble wrapping their minds around how the Mesopotamian cuneiform script functions,” Rutz said.

To write cuneiform, one uses a reed stylus to make wedges on clay. On some tablets, the wedge-shaped marks can be logograms (signs used to represent an entire word, like the dollar sign in English), while other cuneiform signs represent sounds that make up a word’s syllables. Divining the meaning of a series of logograms and syllables involves understanding the interplay of the words and sounds. To add complexity, some cuneiform writing is alphabetic, using a limited number of characters plus a word divider, akin to writing in English.

“When we’re reading something in a book, we have to bring all the information we have about how the words in a sentence fit together to make sense,” Rutz said. “Dealing with an ancient language, this all has to be learned. We don’t have anyone to explain how to decipher the script, how the language works together, and then how we can take the concepts and knowledge of the grammar and render that to an understandable translation.”

With the digital preservation project, Rutz and Lauinger create the opportunity to deepen the understanding of the structure of the ancient language on the tablets as well as the meanings of words or symbols. They can mark up the digital text with notes, generate updated glossaries and allow researchers to tag texts with what they think the role of a particular word is in a sentence, note idiomatic phrases and keep track of words and what they mean in context.

It will also offer the opportunity to read people’s mail from more than 3,000 years ago, Rutz said.

“These include letters between heads of state, to letters from an imperial overlord to a vassal head of a city-state, to just personal correspondence in which people are worried about business, or griping,” he said. “They are a wonderful insight into the everyday.”