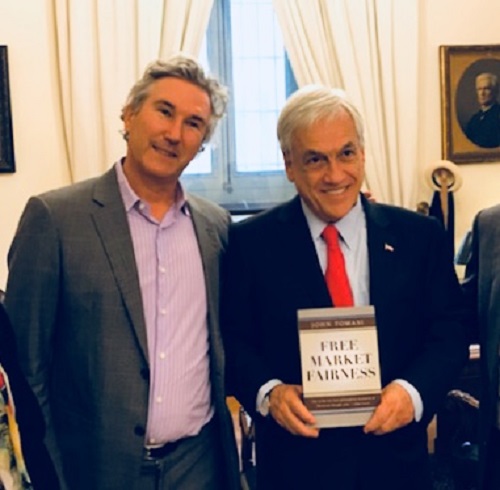

PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] —In June, when John Tomasi, a Brown professor of political science, traveled to Chile to give talks on his concept of “market democracy,” he did not expect to meet the country’s president, Sebastián Piñera. Nor did he expect to launch a yearlong project that could see the market democracy model, which incorporates social justice and private economic freedom, applied at the policy level in Chile.

But for at least the next year, Tomasi will be traveling between Brown and Chile, working on a Spanish translation of his 2012 book “Free Market Fairness,” in which he introduced the idea of market democracy. He will also write a new chapter on how to apply the model to Chile specifically and offer a spring seminar at Brown that will invite students to consider how political philosophy can operate in practical terms.

Tomasi says the projects arose from his visit to Chile, where he gave a series of talks and workshops organized by the Fundación para el Progreso (Foundation for Progress) and the Centro de Estudios Públicos (Center for Public Studies), two think tanks occupying different spots on the ideological spectrum. He also participated in the Latin America Liberty Forum and Diálogos en La Moneda, a series of talks hosted at the presidential palace. The unexpected meeting took place after that presentation, when Tomasi had the chance to speak to Piñera and his advisers about the big ideas in his book.

Alejandro Cajas, director of operations at the Foundation for Progress and Tomasi’s host during his visit, said that the “Free Market Fairness” approach to justice is a model that speaks to Chile’s recent history and could shed light on how the country’s young democracy could face future challenges.

“President Piñera’s administration is trying to put forward an agenda based on a combination of free market and social justice,” Cajas said. “Put simply, it’s a government inspired by the market democracy model.”

From theory to practice

Trained as a philosopher, Tomasi says he had been accustomed to thinking of political philosophy as something of an abstract exercise until the response to “Free Market Fairness” showed him otherwise.

“When you write a book of political philosophy,” Tomasi said, “you don’t know if anybody is going to read it.”

People did read “Free Market Fairness” and sparred over its ideas. Then policymakers, including Sweden’s former finance minister, leaders from The Centre for Civil Society in India and now members of Piñera’s administration, reached out to Tomasi to explore how to apply the concept of market democracy on the ground. In particular, Tomasi said, Gonzalo Blumel, Piñera’s minister secretary general, read the book and worked with Piñera to incorporate its ideas in his successful presidential campaign.

The book’s aim, Tomasi says, is to outline a political philosophy that does not require governments and societies to choose between social justice and economic freedom, but to allow for both.

“The big project in my book is to combine two very different political ideologies, a strong left ideology — socialism, let’s say — and a strong right ideology — libertarianism, let’s say. One side thinks that social justice is the most important moral standard for society. The other side thinks that private property rights are very important.”

While the two ideologies are often considered starkly at odds, Tomasi said, each offers something of value.

“I think there’s a deep insight in both sides,” Tomasi said. “As a philosophical matter, I wanted to combine those into a higher moral ideal that I call ‘market democracy,’ which gives very strong weight to private economic liberty but is also foundationally committed to a socially just society where no one is left behind.”

Market democracy aims to bring the free market back to its roots, Tomasi says, and to create a better world for everybody. It allows for an important role for the state, particularly regarding schooling, while also providing for strong private economic liberty. A society without private economic liberty, Tomasi says, is unjust: it stunts and fails to respect its citizens.

“Socialist policies may intend to do well but tend to have top-down approach and to measure the justice of governments by size of their welfare state,” he said. “Citizens are owed genuine independence, genuine reform.”

That reform requires honest discussion, Tomasi says, rather than a zero-sum game between “bullying and morally condescending” liberalism and “cold and heartless” libertarianism.

‘Pure ingredients’

In Chile, presidents serve four-year terms, and immediate re-election is prohibited. In recent years, the country has tacked back and forth between leaders with very different political outlooks. Michelle Bachelet, a member of the Socialist Party of Chile, and Piñera, generally considered a center-right politician, have served alternate terms as the country’s leader since 2006. Tomasi described a moment in 2014, when Bachelet succeeded Piñera and began her second term as president, that clarified what is at stake where there are hardened political positions.

Representatives from Bachelet’s majority party described plans to reverse the neoliberal policies of her predecessor using the metaphor of a backhoe or bulldozer, Tomasi says. The bulldozer metaphor and mentality, he said, is destructive.

“If we lack a higher moral ideal, each side fears acknowledging the ideas of the other, because if they do, that bulldozer will come and crush them,” Tomasi said. “I prefer the metaphor of the bus — everybody gets on it and we move forward.”

Tomasi says the stark divide between socialist and libertarian philosophers mirrors a divide in American society and in other countries. Proponents of each ideology rejects the other, and little progress is made.

This is where political philosophers can intervene, he says, even when faced with strong opposing political traditions. In Chile, the strong socialist and neoliberal or libertarian traditions comprise what Tomasi calls the “pure ingredients” for market democracy.

In the coming year, with colleagues at University of Adolfo Ibáñez in Santiago, Tomasi will translate and extend “Free Market Fairness” with the chapter focusing on Chile and work with Brown students on how to apply political philosophy to the conditions on the ground in Chile. Those actions could provide something of a roadmap that Piñera’s administration could put into practical application, he says.

“It’s the job of philosophers to find ideals that attract people of good will on both sides,” Tomasi said. “The practical problems of politics around us are, I think, really failures of philosophy. If we could correct it, it could improve our political discussions. It could improve the quality of democracy and of democratic deliberations in countries like Chile as well as the U.S.”