PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — Kasturi Pananjady graduated from Brown in May. Yet there’s one course she can’t seem to quit: Antigones, a comparative literature course focused on a 2,500-year-old work by the playwright Sophocles.

“I’m still tinkering with the final project,” she admitted. “It’s a bit of an obsession right now."

This spring, a close study of “Antigone,” the ancient Greek text, along with several contemporary adaptations revealed to the aspiring journalist some unexpected parallels with her chosen career.

“In a Greek tragedy, the chorus witnesses the plot and reacts to it, but it doesn’t intervene,” Pananjady said. “That’s a good description of journalism also.”

The graduate’s creative final project began by identifying similarities between the plot of “Antigone” and a criminal defamation case involving a journalist who accused a senior government official in India of sexual harassment. Both, she said, elicit questions about systems of judgment and fairness. But the project evolved as Pananjady also became interested in examining the Greek chorus through the lens of contemporary journalism.

“Our first obligation as journalists is to tell the truth,” she said. “But our second obligation is to do as little harm as possible to the regular people whose stories we tell. I’m never sure that I’m striking the right balance there.”

Thanks in part to Sophocles’ timeless storytelling, Pananjady has already begun to confront one of journalism’s biggest conundrums — proof that some ancient texts are still worth studying thousands of years later.

Elizabeth Gray, a visiting assistant professor of comparative literature who taught the course, said that at first blush, “Antigone” might seem like nothing but a relic of antiquity. The plot follows Antigone, the protagonist, as she pursues an honorable burial for her brother Polyneices, a rebel fighter in Thebes’ civil war. When Antigone’s uncle Creon, the new ruler of Thebes, refuses burial rites for Polyneices on the grounds that he was a political traitor, Antigone risks death to perform the ritual herself.

Hidden behind the play’s dated references to punishing gods and old liturgy, Gray said, are timeless lines that touch on protest, sacrifice and the often opposing forces of civil obedience and family loyalty — themes that still resonate two and a half millennia later and make Sophocles’ masterpiece ripe for reinterpretation.

“‘Antigone’ can’t avoid asking questions about gender, about class, about the state versus the individual, about what it means to question the larger systems at work,” Gray said. “It continues to resonate in our contemporary moment even though it’s an ancient Greek play.”

Particularly resonant today are the play’s less-explored questions about war, citizenship and what it means to belong, Gray said. She noticed that recent adaptations of “Antigone” were eager to investigate what happens to people who question the status quo, as Sophocles’ protagonist did. “Antígona Gonzalez,” a book of poetry, uses Sophocles and real newspaper clippings to craft the story of a Mexican woman who searches for her missing brother in the midst of a violent, widespread drug war. And Kamala Shamsie’s novel “Home Fire” reimagines “Antigone” in contemporary London, spinning a tale of a Muslim immigrant family torn apart when one of them leaves for Syria to join the Islamic State group.

“In ‘Antigone,’ we enter into a scene of post-warfare, and the play emerges from that moment,” Gray said. “In contemporary adaptations, we see responses to ongoing conflicts, whether they are wars or political crises. This opened a space for the students to make connections between ‘Antigone’ and today's urgent questions of citizenship and statelessness, when refugees all over the world are seeking safer homes.”

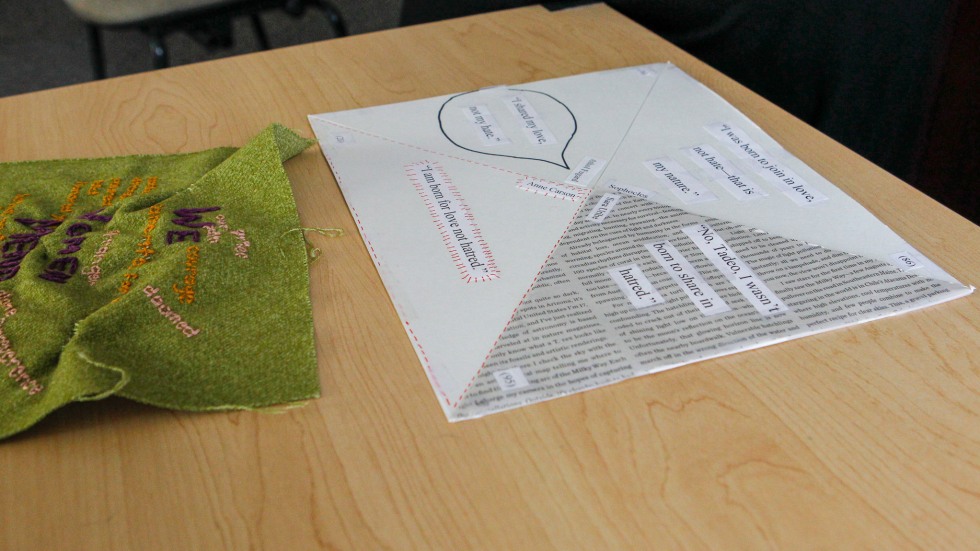

Gray’s course drew in students from a variety of concentrations, including theater, education, computer science and classics — perhaps because it involved more than reading and writing papers. At the end of the course, students prepared and performed different adaptations of “Antigone,” drawing from the literature and from their own personal experiences. They also worked separately on creative final projects, producing visual art, play scripts, and in Pananjady’s case, a “Shouts and Murmurs”-style satirical piece.

Amistad Meeks, a political science concentrator who will be a senior in the fall, said his final project took the form of a series of vignettes that touched on both political and emotional themes.

“What was particularly striking to me were the themes relating to family,” Meeks said of “Antigone.” “The fact that Antigone’s devotion to her family is so strong that she would sacrifice her life for them is such a profound statement. I think this class has helped me solidify in myself what I am willing to do for the people that I care about.”

Pananjady, too, learned something important about herself in the course. As she made her way through a different contemporary adaptation of “Antigone” each week, she repeatedly revisited Sophocles’ play with fresh eyes — forcing her to accept that her own personal opinions could shift dramatically over time.

“It was incredible to sit with the text for so long and to change your mind about it all the time,” she said. “It was a push to think long and hard about what really matters to me.”