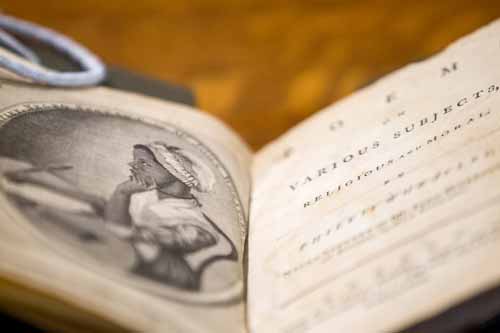

PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — Over the last two years, Shira Buchsbaum has read Phyllis Wheatley’s poetry from a first-edition volume, seen an original illustration of William Shakespeare up close, and touched a 400-year-old book authored, and perhaps even handled, by Galileo.

But Buchsbaum, who graduated from Brown in May, realizes she’s unique among her peers. She’s well aware that few students make hay of their unlimited access to these and other unique items at Brown University’s John Hay Library, home of the University’s special collections.

“‘Special collections’ can be a misleading term,” Buchsbaum said. “It makes it sound like the materials are off limits and need to be protected. When students think of the Hay, they think, ‘It’s so special it doesn’t pertain to my daily studies at Brown.’”

Those common assumptions couldn’t be further from the truth, she said: The John Hay Library is fully accessible not only to students but also to members of the public, who can view whatever they wish after a quick registration at the library’s front desk. And the collections feature such a wide variety of subject matter, from the anthropological to the astronomical, that students from every concentration can find something relevant to their academic interests.

In an effort to dispel the myths and rumors, Buchsbaum, an aspiring librarian, spent her junior and senior years creating Fields of Hay, an online guide to the University’s special collections targeted specifically at undergraduates.

“People today say, ‘Who even needs a library anymore?’” she said. “But they’re critical places for storage and access, and I hope Fields of Hay conveys that. It’s a centralized place where students can search the special collections based on their interests.”

Buchsbaum said she began the project in her junior year at the behest of Heather Cole, the curator for literary and popular collections at the Hay Library. Cole, a passionate advocate for open access and community outreach, wanted to create a field guide to special collections for Brown undergraduates — but she wanted the guide to come from a student, not a librarian.

“I usually have a whole song and dance I do to try to entice students into the library, but their fellow students can often be better advocates and can speak more directly to students' interests,” Cole said. “Students act as ambassadors to the resources we hold. I often talk with students whose friends visited the library and shared stories of what they saw, which then encourages others to visit to see something similar.”

Cole gave Buchsbaum free rein to create whatever kind of guide she thought would best help her peers — and so the Fields of Hay website was born.

Buchsbaum started with the basics: Instructions on how to create an online account to access special collections, how to find and request materials and how to browse librarian-curated collections by subject.

Then, she dove into the collections themselves, familiarizing herself with the academic subjects they touched on. What she learned is distilled in a so-called “concentration field guide” on the Fields of Hay website, which provides a list of special collections that are relevant to each of Brown’s more than 80 undergraduate concentrations. In short, Buchsbaum said, the field guide offers definitive proof that there’s something for everyone at the Hay.

“I already knew a lot about the literature and poetry collections here, but I was looking to provide materials and access points not only to those with similar interests but also to students who study things I have no knowledge of,” the English concentrator said. “We have a brilliant collection on the history of medicine, one on the history of science writ large, and a few unusual scientific objects. It was challenging but worthwhile to find relevant materials for students in STEM fields.”

Buchsbaum’s journey through the University special collections also revealed dozens of hidden gems and wacky stories, some of which she shared on a Fields of Hay page called Material of the Week. Among her findings was an original copy of Shakespeare’s first folio, actor John Krasinski’s senior thesis, and John Ashbery’s 1975 poetry collection “Self-Portrait in a Convex Mirror” presented inside an actual convex mirror.

In September, Buchsbaum is off to London to pursue a master’s degree in the history of the book — but she hopes Fields of Hay continues to entice everyone, from incoming first-year students to tourists visiting from out of state, to cross the threshold into the John Hay Library’s marble foyer.

“Access to materials that make us feel invigorated and connected with our history is incredibly important, not just for general learning but also for the social psyche of a community,” she said. “When we don’t have access to the works of Walt Whitman or Edgar Allan Poe, Americanism doesn’t feel real or relevant. When we do, we can study and critique them in valuable ways. My hope is that Fields of Hay contributes to that work in a very small way.”