PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — No bells or bagpipes filled the air, no procession of excited students marched through the historic Van Wickle Gates and no community congregated on the College Green to welcome the 2,794 students who will begin their scholarly careers at Brown University in the current academic year.

Yet even in a time that will be remembered more for COVID-19 than for convocation and commencement ceremonies, Brown University marked the official launch of its 2020-21 academic year with its 257th annual Opening Convocation on Tuesday, Sept. 8.

The virtual ceremony was live-streamed to an audience of more than 800 new graduate students and 144 first-year medical students — most of whom have started courses this fall — as well as the undergraduates who will begin their Brown careers more formally in January as part of Brown’s modified three-term academic year.

Current students, faculty, staff and alumni tuned in as well, and everyone looked forward to the possibility of a formal, in-person Opening Convocation to be held in January 2021, should public health conditions allow.

Presiding over her ninth Opening Convocation ceremony, University President Christina H. Paxson noted that, although this year’s event looked different from years past, the spirit remained the same. She welcomed incoming students with a nod to the extraordinary circumstances under which they start their Brown journeys: a moment in history marked by racial-justice activism, socioeconomic inequality, extreme climate change, high levels of political polarization and the global coronavirus emergency.

“Grappling with these challenges requires the concerted and thoughtful efforts of people across disciplines,” Paxson said, encouraging the incoming scholars to collaborate with classmates and colleagues across the Brown campus.

Though the many academic disciplines at Brown advance knowledge on concerns of such consequence, Paxson argued that it’s especially important to remember past lessons relevant to 2020’s challenges. There’s much to glean from the experiences of previous generations, even if the lessons require a bit of investigation.

“Our histories are imperfect and incomplete,” Paxson said. “Over time, societies often led by those in positions of power selectively choose what we will honor and remember. And when this happens, it falls on scholars to unearth what was forgotten.”

Paxson pointed to the 1918 influenza pandemic, the passage of the 19th Amendment and Brown’s historical ties to the trans-Atlantic slave trade as powerful examples of looking toward the past to inform the future. Until last spring, the 1918 pandemic had largely vanished from public consciousness, she noted.

“We now know that those living in this time experienced school closures, event cancellations, resistance to mask-wearing directives, in addition to experiencing the trauma of illness and death of loved ones,” she said. “In hindsight, it’s clear that we could have been better prepared for today’s challenges if the influenza pandemic had not been all but forgotten.”

Speaking about the often misremembered history of the 19th Amendment, ratified 100 years ago to give women the right to vote, Paxson reminded viewers that it didn’t actually guarantee all women the right to vote.

“For many women, it meant that they had simply gained the right to be disqualified from voting for the same reasons that already applied to men — failure to pass literacy tests or pay poll taxes, supposed immorality or insanity, felony convictions and more,” she said.

Paxson introduced incoming students also to the University’s historic ties to slavery, noting that this fall, every first-year and transfer student will read Brown’s Slavery and Justice report, published in 2006 after a detailed inquiry by a steering committee of University students, faculty and administrators.

“It is our responsibility to expose that history, look unflinchingly at its current, terrible manifestations and become part of a process of healing as we deepen our understanding together to effect change,” she said.

Paxson challenged the incoming class to deliberately mark the trials of this year in their personal consciousness and memorialize the adversity they face: “How we act as a community now defines how we’re remembered in the future,” she said. “Let’s make sure it’s a year that’s never forgotten.”

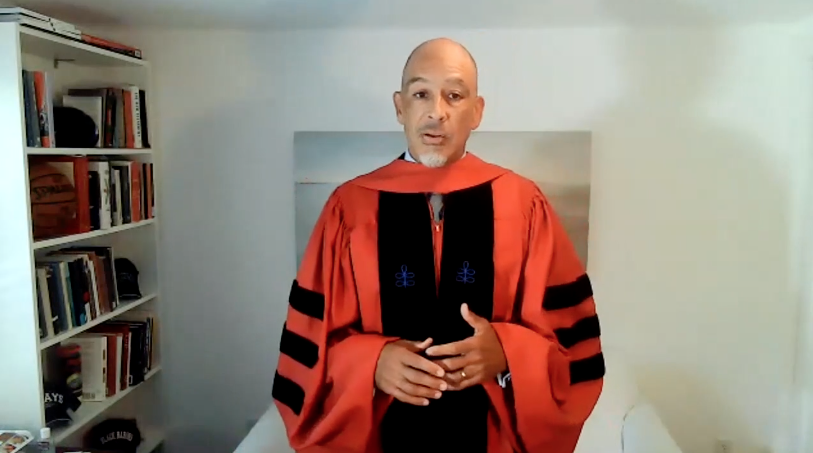

While Paxson encouraged students to learn from the past, keynote speaker Andre Willis, in an address titled “The New Normal,” urged them to step into the new academic year with a robust sense of morality inspired by the current milieu.

“The new normal we make should be guided by the habits that have driven Brown’s response so far — habits of mutuality and fallibilism,” said Willis, an associate professor of religious studies. “Mutuality is the habit of shared, equal connection, and fallibilism is the capacity to change one’s mind.”

The former asks, “How can I be a better friend?”; the latter, “How can I be a better thinker?” Willis noted. Those questions, coupled with not being afraid to forge new connections or change one’s mind in the face of new information, can serve as a blueprint that Brown’s newest students can use to build their futures.

“Brown will be what we make it,” Willis said. “And whether we like it or not, together, we create the post-COVID-19 way of being for this university.”

That way should be paved with the idea that one’s academic work simply cannot be fractured from the rest of their existence, he said: “Scholarly endeavors always speak to the needs of the world in one way or another, thus, to engage in the life of the mind is to engage in the life of the world,” he said.

By embracing that connection, the academic world is uniquely poised to consider, engage and confront big-picture issues, particularly those that Paxson outlined in earlier in her address.

“We ignore these problems... at our own peril, and we confront them practicing habits of mutuality and fallibilism for the preservation of something greater than just this University — that something is intellectual integrity.”

Working to solve the problems that define this generation can seem like an insurmountable task, especially in a time that is marked by immense grief and feelings of powerlessness. But education is one of the single most crucial acts of resilience and tenacity one can undertake, he said.

“I want you to remember that hope is a consequence of action,” Willis said. “The action you are called to is study. For what does it mean to be a student at a time when the world seems like its spinning out of control? It means that education cannot either luxury or a distraction — no, study is a sign of empowerment and growth of the moral imagination. A serious commitment to learning should be thought of as a moral act, especially in the midst of crisis and upheaval.”

It’s not easy work, Willis acknowledged. But it’s the kind of ethical obligation that is non-negotiable in creating the new normal.

“The road ahead will be rocky, but if we all chip into help with the work in front of us, we will have a positive effect on the variety of problems we’re now facing,” Willis said.

“You’re officially in the Brown family, so let’s get it.”