PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — A new $220,000 grant from the U.S. National Park Service will enable two Brown University graduate students to launch a digital project that will shed light on the stories of lesser-known Japanese American internment camps throughout the Western United States.

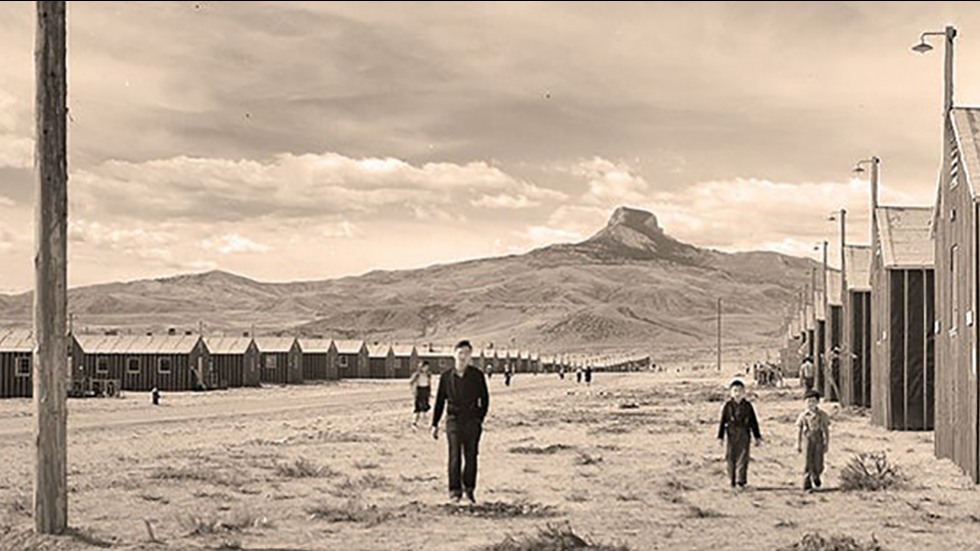

The grant will allow Nicole Sintetos and Erin Aoyama, both Ph.D. candidates in American studies at Brown, to visit five remote sites where Japanese Americans and first-generation Japanese immigrants were confined during World War II. At each of the sites, the pair will collect personal stories and historical background, take drone and three-dimensional images, and meet with members of the local communities.

The project will culminate in the creation of an interactive digital portal into the past — one they say will help people of all ages understand the complex history of Japanese American internment, settler colonialism in North America, and the links between historical and current injustices.

“We’re trying to extend the map of where we consider Japanese American incarceration to have happened during World War II,” Sintetos said. “But our work goes beyond World War II history — we also want to look at the relationships between internment, the military-industrial complex and settler colonialism. Many don’t know that some of these sites of incarceration are still in use by the military today, or that some have lots of tangled history with Native American populations. We want to bring all this history out.”

In 1942, amid the tensions of the war, a controversial executive order signed by President Franklin D. Roosevelt authorized the U.S. military to remove and incarcerate an estimated 120,000 Japanese immigrants and Americans of Japanese descent. Families living on the West Coast and elsewhere in the U.S. were forced out of their homes and taken to dozens of temporary assembly centers and more permanent internment camps in remote areas across the West and in Arkansas.

Thanks to popular literature and movies, many Americans know about Manzanar (in California) and other large, well-documented camps. Using digital tools, Sintetos and Aoyama hope to tell the lesser-known stories of internment sites such as Baca Camp, now Old Raton Ranch, in New Mexico, and Fort Richardson in Alaska — sites that are more remote or difficult to visit.