PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — When Brown University launched the Hassenfeld Child Health Innovation Institute in 2016, the vision was ambitious from the start. Priorities included addressing the impact of poverty on child health, making Rhode Island one of the world’s healthiest places for kids and serving as a national model for advancing family health.

That bold vision required a broad coalition. Brown already had the academic talent and abundant connections to community organizations, but what was needed was a way to bring everyone together to expand upon individual projects, dig into the root causes of the most intractable issues in children’s health, and devise, test, implement and refine approaches to addressing those challenges, sharing that learning with the community — and the world — along the way.

With a $12.5 million gift from the family of retired Hasbro chairman and CEO Alan Hassenfeld, the University established the Hassenfeld Child Health Innovation Institute to provide just that infrastructure. A collaboration between Brown’s School of Public Health and Warren Alpert Medical School with Hasbro Children’s Hospital and Women & Infants Hospital, the institute encompasses a network of clinicians, researchers, students, child health experts and community organizations, all involved in big-idea projects for the state’s smallest residents.

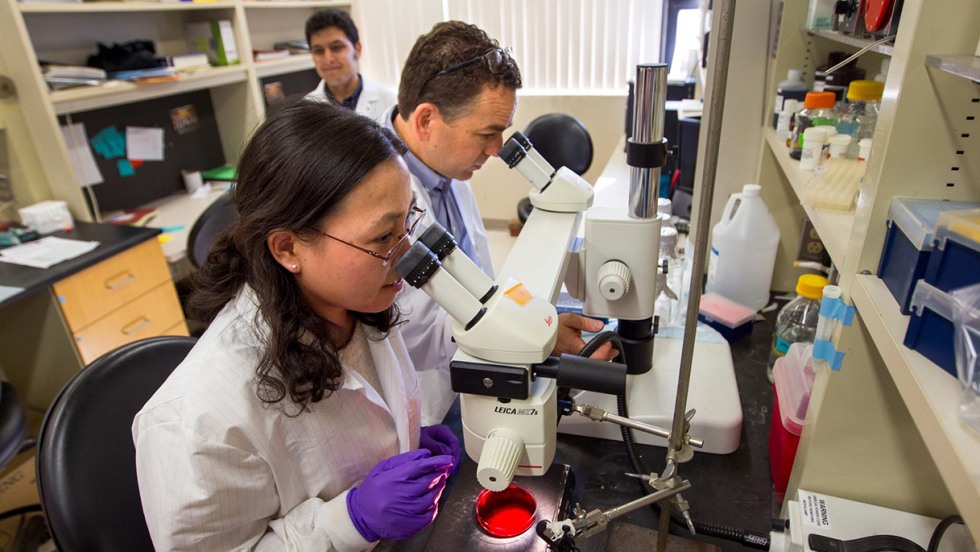

Soon after its founding, the institute started enrolling pregnant mothers and their babies in a long-term observational study. Today, the Hassenfeld Study provides a valuable framework for research in many areas, and is used to investigate child health issues and discover solutions involving the careful coordination of medical treatments, social services and public health interventions. In 2019, nearly $15 million in federal grants was awarded to scholars affiliated with the institute for studies that rely on this data collection effort.

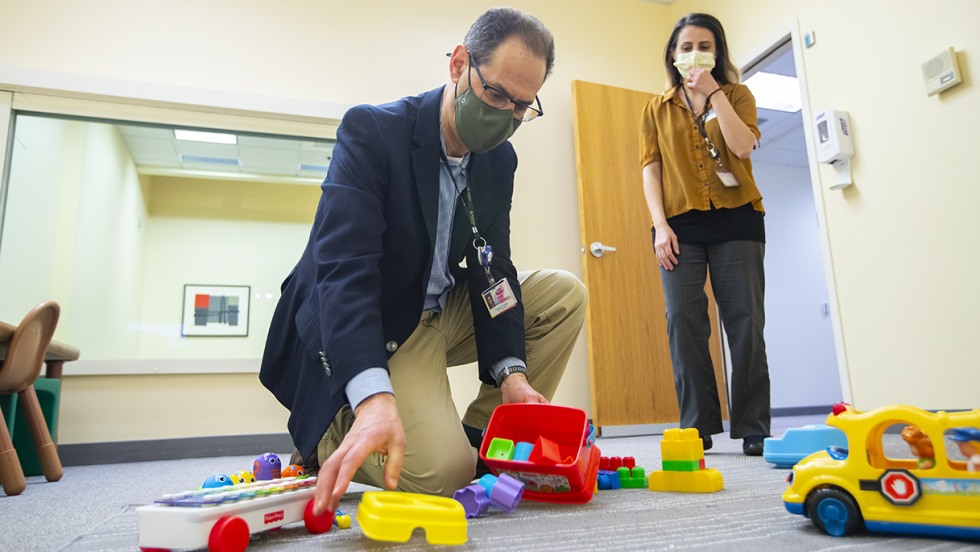

As the Hassenfeld Institute approaches its five-year mark, leaders say its impact has been significant. Based on early projects, families affected by autism are learning more about their child’s specific diagnosis and what treatments might be available; 730 children with asthma in high-risk areas are being screened for severity and offered services based on their needs; and thousands of children from low-income communities across Rhode Island have participated in free summer camp programs that emphasize physical activity and include healthy lunches. All of these programs are engineered for exponential influence: they are being studied and refined so that the results can help countless more children worldwide.