PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — Almost as soon as Dr. Ramu Kharel arrived in Nepal as part of his Brown global fellowship to research emergency medicine programs there, he found himself in the middle of a national crisis. A second wave of the COVID-19 pandemic was crashing over Nepal, causing its already-weak health care infrastructure to collapse.

“While the international focus was on India, this country of nearly 30 million people was drowning in the pandemic,” Kharel said.

Kharel — who had treated COVID-19 patients as an emergency medicine doctor with the Miriam Hospital in Providence and is an affiliated fellow with Brown’s Center for Human Rights and Humanitarian Studies — immediately teamed with health care workers, government officials and NGOs to provide a multitude of creative and effective relief strategies. He has led training sessions for health care providers, advised local government leaders on COVID management protocol and consulted with health centers on treatment and resource management. Kharel, who just returned to the U.S. this week (a month later than he'd originally planned), responded to questions about efforts to address the pandemic abroad.

Q: What was the state of the COVID-19 situation when you arrived in Nepal on April 1?

Within the first 15 days of my arrival, COVID cases started to explode in India, and then not long after that, per capita cases in Nepal were even higher than in India. The border between Nepal and India is around 1,100 miles long, and it’s practically impossible to control all traffic from one country to the other. The rate of viral infections in Nepal was as high as 90% in some districts, especially those bordering India. There was a major lack of oxygen supply, testing was inadequate, very few people had received the vaccine and ICU beds were rapidly filling up.

Q: How did your experience in Rhode Island prepare you to help on the ground in Nepal?

Over the last year, I spent a lot of time treating COVID-19 patients and working at the field hospital at the Rhode Island Convention Center. Through Brown as well as Project HOPE, the global health and humanitarian organization, I’d also been participating in trainings with more than 55 countries on the principles of treating COVID-19. We’d done a three-day training on different concepts. Those experiences really put me in a prime position, when I got here, to help out.

Q: As part of a larger Center for Human Rights and Humanitarian Studies / Project Hope project to provide COVID-19 training for health workers, you’ve led training on clinical management and vaccines for health providers in Nepal. What impact do you think that training will have?

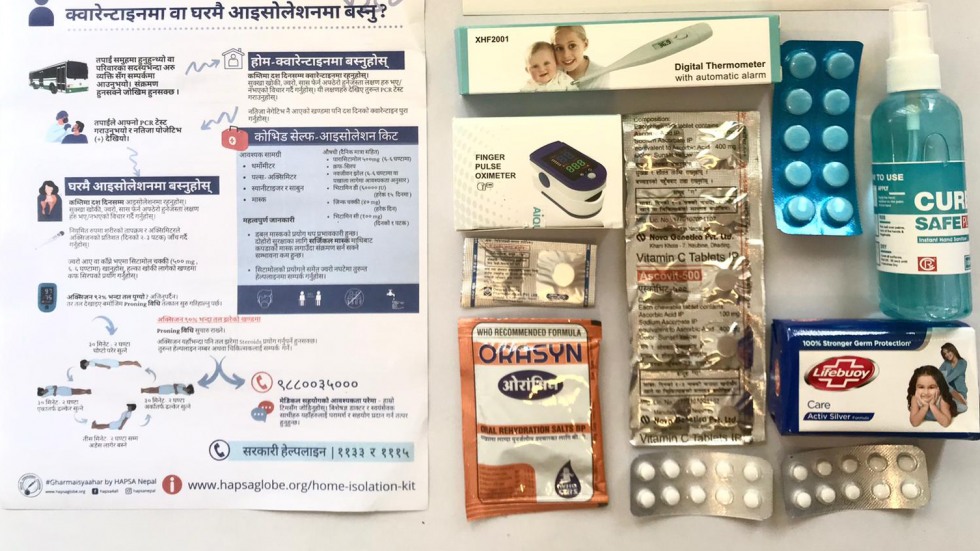

One 4-hour video training was attended by 300 doctors, nurses, health workers around the country, which was the maximum number allowed on my Zoom. The feedback has been tremendous. It is very clear that we do not have enough to equip health care workers working on the frontlines to fight this pandemic, and one of the gaps is basic clinical management knowledge. With my NGO, HAPSA Nepal, we also conducted a 2-hour training with a focus on isolation/surge center staff. This has also been well received. To help this reach more municipalities, we’re posting the videos online. When we put the 2-hour training video on YouTube, there were 4,000 views right away. There is a high need in Nepal to train and equip frontline health care workers with COVID-19 clinical knowledge.