PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — Just days after the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks, Paul Myoda picked up the phone in his Brooklyn apartment and called Julian LaVerdiere, a friend and colleague.

“Julian and I were talking about how ground zero looked,” Myoda said. “It was illuminated by these searchlights that made the smoke look like a sort of ghastly illuminated plume. We thought, it’s almost as if we can still see and feel the buildings, even though they’re not there anymore — like they’re phantom limbs.”

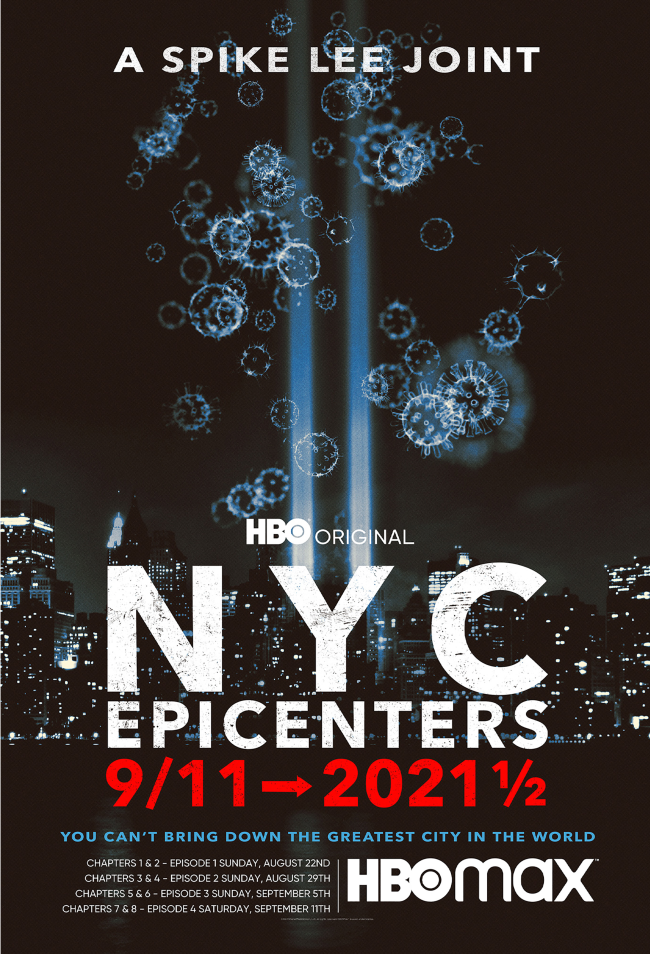

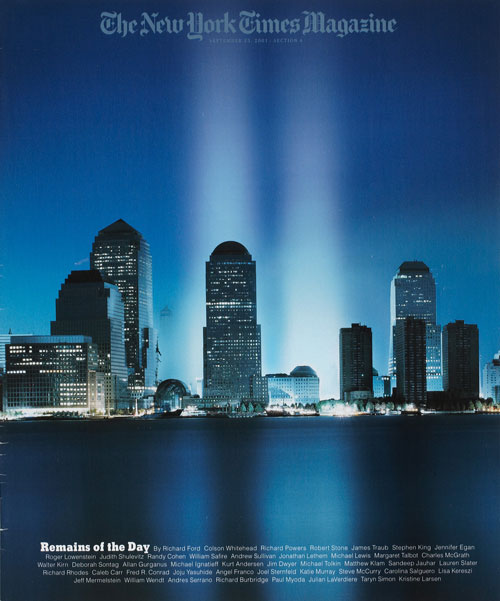

They transferred their “phantom limb” vision to the page, creating an illustration of two skyscraping pillars of light at ground zero; it graced the cover of the New York Times Magazine on Sept. 23, 2001. Six months later, the illustration became “Tribute in Light,” a real, physical art installation at the former World Trade Center site. The pair’s piece received so much acclaim that it continues to appear at the site every year on Sept. 11.

Even now, on the 20th anniversary of the attacks, Myoda — today an associate professor of visual art at Brown University — remembers the surreal day the piece debuted six months later, in March 2002.

“It felt as if the whole city paused,” Myoda said. “It stopped everyone in their tracks. All these boats gathered in the harbor and, after a minute of silence, they leaned on their horns at the same time. It seemed like the sound of foghorns was echoing through all of New York.”

The conception of “Tribute in Light” may sound spur-of-the-moment, the artist said, but it was actually three years in the making.

In 1998, the public arts organization Creative Time approached both Myoda and LaVerdiere and asked if they were interested in creating public art installations to mark the new millennium and the first mapped human genome, expected to be completed in 2000. The artists were both fascinated by bioluminescent organisms — living beings that emit light, such as fireflies and particular types of dinoflagellate algae — and decided to team up on a project focused on bioluminescence.

“We decided we wanted to make a bioluminescent beacon and put it where everyone could see it: on top of the World Trade Center, the tallest building in New York City,” Myoda said.

The two artists split their time between a laboratory in the American Museum of Natural History, where they bred bright dinoflagellates, and a studio in one of the twin towers, where they installed test beacons and drove around the New York City area to view their work from different angles.

Just weeks after the pair had vacated their World Trade Center studio, the towers collapsed and New York City turned upside down. The pair’s bioluminescent beacon would never debut, but its development helped inform the creation of “Tribute in Light,” a piece that, in keeping with the original vision, could be viewed everywhere across the city.