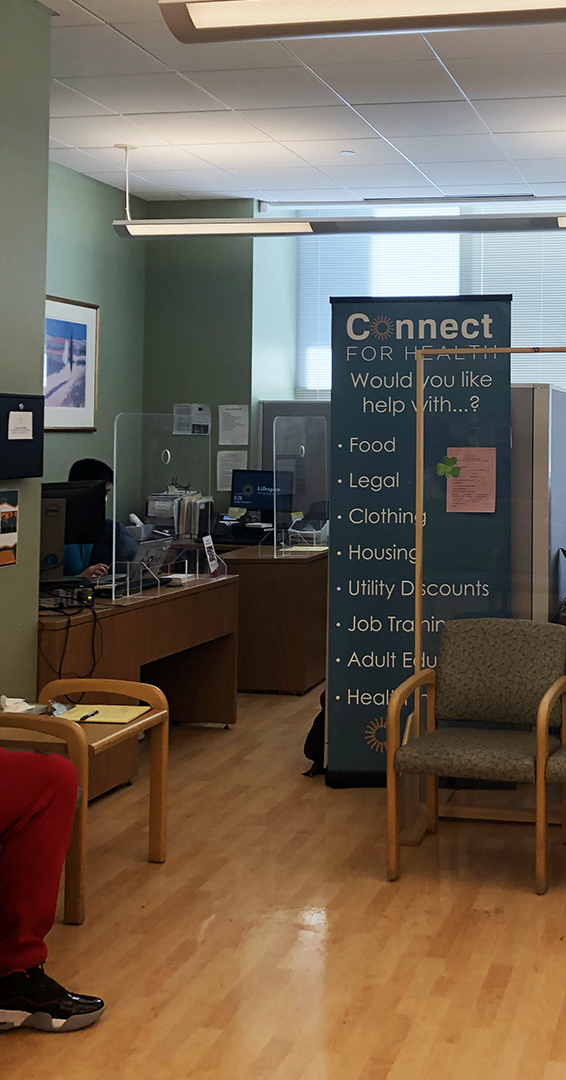

PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — In the waiting room of Lifespan’s Center for Primary Care at 245 Chapman St. in Providence’s Washington Park neighborhood, a can’t-miss sign greets visitors. It reads, “Would you like help with…?” and then lists options: food, legal, clothing, housing, utility discounts, job training, adult education and health care. The sign is positioned in front of an area that looks more like a bank than a health clinic: Two college students, both seniors at Brown University, are seated behind computers, patiently waiting for the chairs in front of them to fill.

Five years ago, the sign caught the eye of Gina, a 59-year-old mother of three and grandmother of four, while she visited the clinic for a doctor’s appointment. “I was like, ‘Wow, what’s this?’” she said. Gina thought to herself, “As a matter of fact, I could use a little help.” She’d recently lost her job at a nursing home for patients with Alzheimer’s and dementia, and she had started suffering from serious back pain. Unemployment wasn’t covering the bills, she said, and it felt like nothing was going right. Intrigued, Gina approached the table.

The students explained that they were volunteers with Connect for Health, a program run by Lifespan’s Community Health Institute that aims to address people’s basic resource needs to improve overall health and well-being. Part of their process is to talk with patients about needs and link them with resources to help.

Over time, Connect for Health volunteers have helped Gina locate local food pantries, sign up for food assistance, receive discounts on utilities and apply for COVID test kits. Gina continues to be amazed by the students’ professionalism and dedication. They throw themselves into addressing her issues, she said, but they never ask her to explain her circumstances or justify her requests.

“They just really want to help me,” Gina said.

Problem-solving student volunteers like the ones Gina met are the workforce of Connect for Health. These advocates, as they’re called, serve as liaisons between patients and community and government resource programs. At the Center for Primary Care (part of Rhode Island Hospital) as well as Hasbro Children’s Hospital, they talk to patients about issues like food or housing insecurity; they make connections and phone calls; they follow up and follow through. They parse eligibility requirements, research opportunities and spend hours on hold and online, looking for ways to meet patient needs. Their goal is to empower patients in need to find both short-term solutions and long-term stability.

“The students are a highly regarded and valued part of the patient’s care system,” said Carrie Bridges Feliz, Lifespan’s vice president of community health and equity. “We don’t know what we’d do without them.”

Powered by students, focused on patients

While Connect for Health welcomes students from multiple institutions — including Rhode Island College, Providence College and Grand Canyon University — Brown University is their largest and oldest academic partner, Bridges Feliz said. At any given time, she said, around 80% of the 175 undergraduate and graduate student volunteers are Brown students.

The program itself launched more than 20 years ago, but the current organizational model, which came together at Brown, has allowed the volunteer program to grow and expand, Bridges Feliz said. Many students stay in the program for four or even six semesters, and the program is structured so that advocates have the opportunity to advance into leadership roles.

At the top of the organizational chart, though, is the patient.

“We’re all working for the patients,” said Michelle Wheelock, a licensed clinical social worker and one of two Connect for Health program coordinators. “This is the first time I’ve worked somewhere where the patient is at the top of the hierarchy.”

Connect for Health addresses social determinants of health — the non-medical factors that influence health outcomes — a concept Brown senior Kush Patel knew well before joining Connect for Health in 2019. Patel had recently taken “Health Care in the United States,” a required course for undergraduates in Brown’s School of Public Health taught by Dr. Ira Wilson, a professor of medicine and health services, policy and practice.

“Professor Wilson’s course helped open my eyes to the social inequities faced by people across the nation and also right here in Providence, and how much social determinants influence their health,” said Patel, who is concentrating in neuroscience.

After learning about the outsize role played by social factors, Patel wanted to do more to address them. In his two and a half years as a Connect for Health advocate, he has connected families to resources that provide food, clothing and other essentials. The summer Patel started, he was assigned to the case of a recently divorced father, a non-English speaker, who was going through an acrimonious divorce.

It took more than a year of connecting with a translator, a physician and a lawyer, but Patel was eventually able to get him the legal assistance he needed.

“That was definitely challenging and emotionally draining, but it felt really good to finally get everything sorted for him,” Patel said. “That’s one of the best things about the program: The gratitude that clients have for you at the end of every conversation. You get the sense that sometimes you’re the only person who is helping them, the only person who they’re talking to about their lives. And that keeps you going.”

For Grace Molera, a Brown senior neuroscience concentrator and Connect for Health team leader, one of her most meaningful cases involved helping a family who’d just immigrated to the U.S. They spoke only Swahili, so Molera talked to them with the help of an interpreter.

“At first, they needed transportation to their medical appointments,” Molera said, “but then we were able to help them find the best way to get to the grocery store. I also showed them how to change their language preference in Google Maps so that they could find bus routes to get around Providence.”

Eventually, the family confided that they were having trouble affording food, so she helped them apply for government assistance. Molera said this was a great example of the interconnectedness of patients’ needs, and how factors like transportation and food insecurity are related. She was also grateful to be able to work with the same family over the course of several months.

“Once you have that longer-term relationship, it can help clients feel comfortable about coming to you with more personal issues, and you can find additional ways to help them,” she said. “You can see people’s confidence build a lot during the time that you’re working with them.”

That’s an important aspect of the program: Helping people build or rebuild their lives. A patient named Chanthol, a Providence resident, discovered Connect for Health when he was in the hospital with a broken heel. He was about to be discharged, but had no house or apartment to go home to. Program advocates counseled him about applying for rent relief, and then, after he eventually found a suitable apartment, helped stock his new home with essentials like paper towels. Chanthol’s student advocate has been working with him to find a new job in customer service, while he’s also been proactively searching on his own.

“The people at Connect for Health gave me the strength and courage to believe in myself and move on, and carry on with life,” Chanthol said.

Support for patients and for patient advocates

In fiscal year 2021, Connect for Health volunteers screened 3,462 patients, identified 7,792 needs and successfully resolved 81% of those needs.

There are times, though, where not even the most dedicated volunteer can solve a patient’s issue.

“We’ve all had instances where there doesn’t feel like there can be much done to help a client, and that can feel incredibly disappointing,” said Hannah Thomas, who volunteered with Connect for Health from the summer after her first year at Brown through the spring of her senior year, and is now completing a fifth-year master’s degree at the School of Public Health.