So Bai decided to conquer his fear, laying bare his vulnerabilities. He participated in English language workshops on campus, joined the Brown Swing Club and held Chinese language conversations with fellow students. Those interactions led to deep connections with others at Brown and gave Bai enough confidence to march alongside his peers in support of Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders.

“In my own journey at Brown, I realized that if I abandon fear and stay true to myself and others, eventually vulnerability leads to courage and strength,” he said. “Vulnerability really connects us, because we have all been through a tough time. It gives us the foundation to trust and support each other.”

He advised his fellow graduates to never forget their vulnerability, because it is the key to remaining compassionate and effecting positive change: “I hope you maintain a strong, trusting heart — a heart that can still feel vulnerable; a heart that is open and tolerant to uncertainty; a heart that can relate to people who are still suffering in the world.”

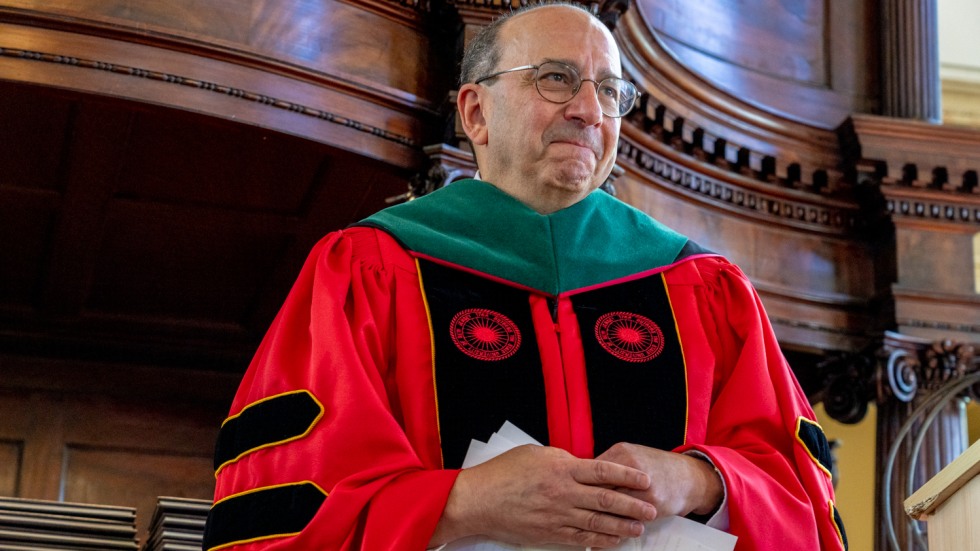

In a tribute to open-hearted science, the Graduate School paid special recognition to astrophysicist Brian Keating, a Brown master’s and Ph.D. graduate, at the doctoral ceremony. Keating, now a professor of physics at the University of California San Diego, was awarded the Horace Mann Medal, given each year to an alum who has made outstanding contributions to their field. Dean of the Graduate School Andrew Campbell said that Keating is currently working with researchers from 35 global institutions to construct an observatory in the Atacama Desert of Chile — the largest ever cosmology collaboration — and regularly translates the impact of his research to the public via a top-rated podcast series called “Into the Impossible.”

And Ph.D. graduates showed their appreciation for one particularly open-hearted staff member: Lorraine Mazza, manager of graduate studies in the Department of English. Mazza, a 44-year veteran at Brown, was given the Wilson-DeBlois Award for her enduring support of the graduate student community and for “making herself available as a friend and confidante,” said doctoral candidate Beenish Pervaiz.

‘Scholars of uncertainty’

For the M.D. Class of 2022, training to be doctors during the height of the pandemic underscored one of the biggest and most humbling lessons of their profession: contending with the fact that they’ll never have all the answers. Uncertainty is a given in medicine, said Adriel Barrios-Anderson in his address to fellow Warren Alpert Medical School graduates at the First Unitarian Church on Sunday.

“This space or gap between what we know and what we don’t is the uncertainty that we are called to navigate throughout our entire careers as physicians,” he said.

Even though they just received their degrees, Brown’s 2022 medical graduates are already unusually familiar with this aspect of the medical profession — as is the M.D. Class of 2020, a dozen of whom joined the in-person procession and Commencement ceremonies, two years after the pandemic postponed plans for their own.

“Many of us entered the hospitals right when the world told everyone to stay out of them,” Barrios-Anderson said. He praised his classmates for using what they did know to help out during the chaos of the pandemic, by supporting overflowing clinics, helping with call lines, working for the Rhode Island Department of Health, and participating in research efforts to better understand the impact of the pandemic on vulnerable populations.