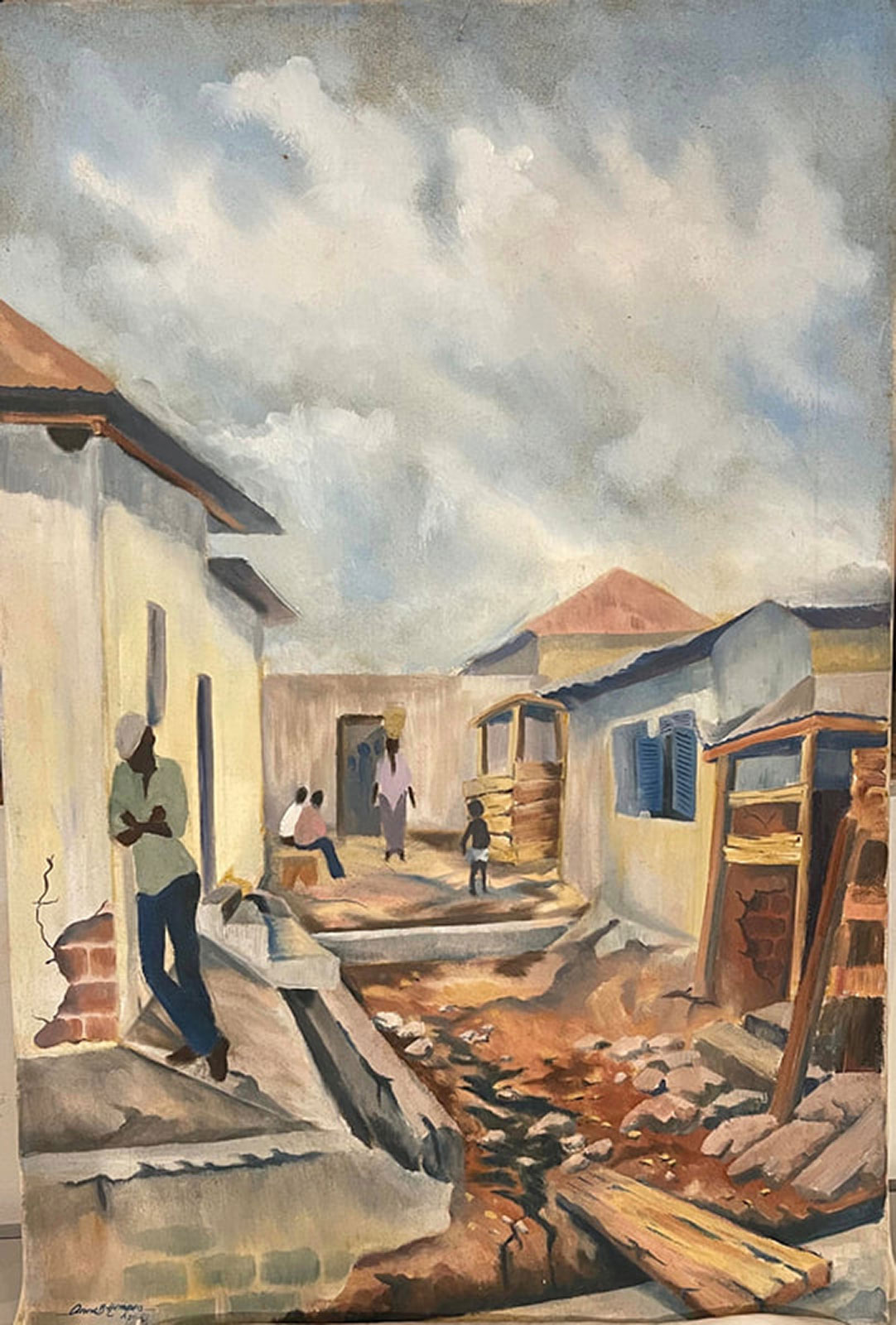

PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — In 1982, amid an attempted coup that led to Ghana’s near-total economic collapse, Anne Blankson-Hemans tore up a bedsheet, stretched it over her own handmade wooden frame and painted a portrait of life in her Ghanaian market town.

Forty years later, her oil painting, “Alley at Ayigya,” is part of an exhibition at Brown University featuring art and traditional objects from times of political upheaval in Ghana, Nigeria and other West African countries that were once British colonies.

The unique exhibition, called “‘A Verry Drunk Hunters Dream’: Modernist Expression in Africa,” opened on Thursday, Sept. 15, at Brown’s Haffenreffer Museum of Anthropology and is the first to be held there since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. The exhibition was conceived in part by students at the Rhode Island School of Design, and was co-curated by Haffenreffer Museum Curator Thierry Gentis and RISD Professor Bolaji Campbell.

Christina Hodge, associate director of the Haffenreffer Museum, said the exhibition captures a period in modern history when West African artists were mixing techniques from their ancestors and from Western countries to depict the upheaval they were witnessing.

That was certainly the case for Blankson-Hemans. With Ghana in dire economic straits, her art school was low on funds for supplies at the time, hence the ad-hoc bedsheet canvas. The school closed for an entire year in the midst of bitter political division and accusations of corruption, interrupting her undergraduate studies, she wrote in a blog post. Yet Blankson-Hemans remembers the time in which she painted “Alley at Ayigya” as a period of happiness and freedom, when she was studying Russian landscape painter Isaac Levitan and experimenting with impressionistic techniques.

The artist forgot all about the painting, she wrote, until she received a message from RISD student Jack English in Spring 2022. As part of a course called “Curating the Modern,” English explained, he and his classmates were developing their own exhibition of modern and contemporary art from Nigeria and Ghana. The student wanted to know more about the painting’s provenance.

“The memories came flooding back thick and fast as though it were yesterday,” Blankson-Hemans wrote. She recalled specific subjects in the painting: “It wasn’t just the memory of the man, drunk and half asleep, trying to balance on an incline… it was also the memory of the small plank of wood that made up the makeshift footbridge.”

Hodge said that the exhibition’s namesake, “A Verry Drunk Hunters Dream,” was also created in a turbulent time in West Africa. The massive dyed-cloth artwork by Susanne Wenger, an Austrian-Nigerian artist and Yoruba priestess who died in 2009, features abstract scenes from dreams of a hunter who has indulged in too much palm wine, a staple beverage in Nigeria and Ghana. Wenger made it in the early 1960s amid Nigeria’s newfound independence from Britain’s colonial rule — a time, Hodge noted, of celebration and dreaming in that country.

Among the other eye-catching items in the collection are printed and woven textiles, wooden and metal sculptures, royal paraphernalia, plastic dolls and a “fantasy coffin” shaped like a fishing boat. Hodge explained that in coastal Ghana, some families commission artists to create coffins in unusual shapes — animals, cars, cigarettes — for their deceased relatives. The “fantasy coffins” have captivated the international art world so intensely that today, some artists create the coffins with art museums, not families, in mind.

“The ‘fantasy coffin’ in the Haffenreffer Museum’s collection is in the shape of a fishing boat and was probably intended for a fisherman,” Hodge said. “It was never used and ended up being sold into the folk art market. But what it depicts is something so fundamental to life in Ghana — fishing, the waterways, boat culture, fish market culture.”