Whitney McMahon was sharing stories of what her 11-year-old son Peyton likes to do at home. Peyton isn’t interested in toys, she said, and instead prefers to suds-up dishes in the sink, pull all the toilet paper off the roll or climb into the clothes dryer. As McMahon showed a photo of Peyton peering out of the dryer’s unmoving drum, grinning from ear to ear, another mother burst out, “Yesssss!!!!”

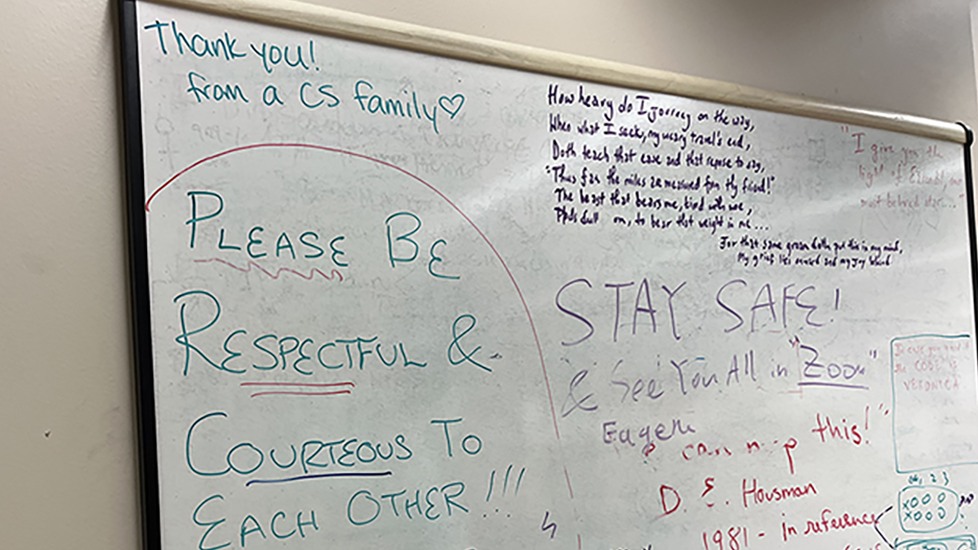

McMahon had been asked to share what it’s like to be a parent of a child with a disorder called Christianson syndrome. Her stories came during a biennial conference for families, held from Oct. 20-22 this year and organized collaboratively by the Christianson Syndrome Association and Brown University’s Center for Translational Neuroscience. Most of the meetings took place at a Providence-area hotel, where families had ample opportunity to connect, swap strategies and learn about the latest research on the autism-like cognitive disorder that had unexpectedly changed the trajectory of their lives.

Christianson syndrome is an X-linked genetic disorder, caused by mutations in the SLC9A6 gene, that affects brain development. Symptoms, which mainly affect boys, appear in early childhood and include epileptic seizures, delayed development and cognitive disability, as well as serious difficulties with speech, balance and mobility that can worsen over time. C.S. is estimated to affect between 1 in 16,000 to 100,000 people, and treatments are extremely limited.

“Everyone’s experience is a little different, but there are similarities,” McMahon said.