Leading public historians have taken notice of the CSSJ’s growing influence — and they’ve enlisted the center’s help in telling the global story of slavery.

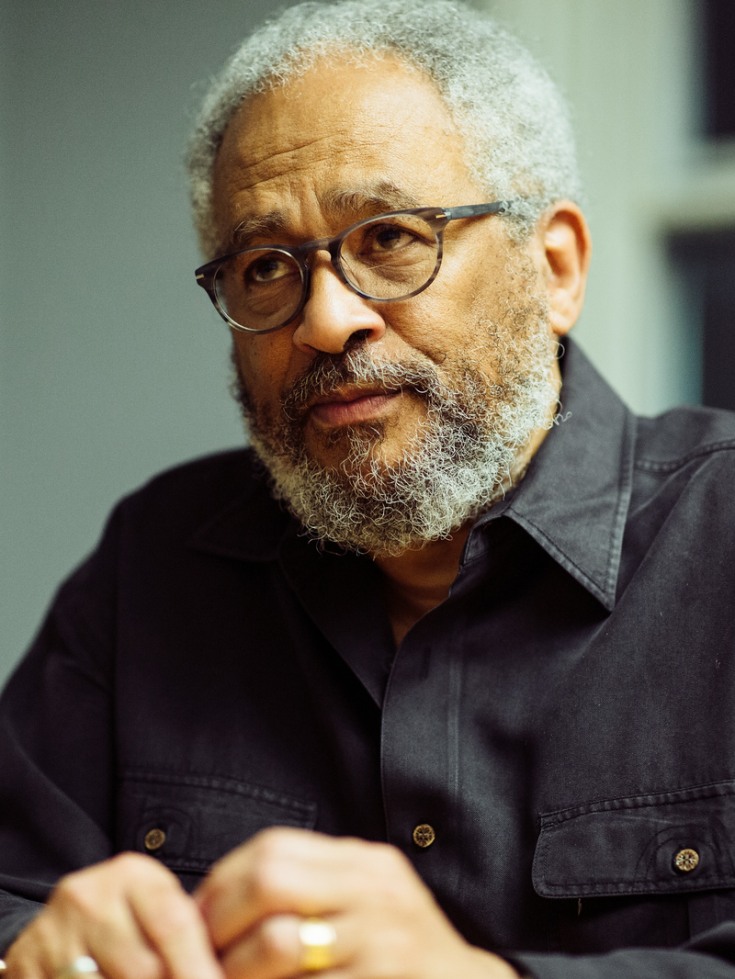

In 2017, award-winning director and MacArthur “Genius” Fellow Stanley J. Nelson Jr., who has examined the history and experiences of African Americans in films like “Freedom Riders,” tapped students and faculty at the CSSJ for help researching a forthcoming documentary that will chart the economic and human cost of the slave trade across the Atlantic basin. The four-part documentary, “Creating the New World: The Transatlantic Slave Trade,” is expected to air on PBS.

Students at Brown enriched Nelson’s historical narrative through independent research projects that drew on their own strengths and scholarly interests. In 2019, while studying for an Atlantic history course, Class of 2021 graduate Jamie Solomon came across a book on enslaved Haitians who rebuilt their lives in Cuba, which proved critical to Nelson’s effort to spotlight untold stories. And Kaela Hines, a Class of 2022 graduate, spent part of Fall 2019 reading the diary of a British official stationed in the slave-trading port of Calabar, Nigeria.

“I feel that the research we do is important and will educate people about a topic that is generally known, but often not in the intricacies we are researching,” Hines said.

The CSSJ’s robust public-facing research initiatives don’t end there. The center is home to a number of research clusters that reach across multiple disciplines, focusing on such topics as structural racism in biomedicine and the complexities of modern-day slavery.

As part of a research cluster on human trafficking, Assistant Professor of American Studies Elena Shih recently worked with the grassroots collective Red Canary Song to host a thought-provoking art exhibition and talk on the one-year anniversary of the Atlanta massage spa shooting. The event gave members of the Brown and Providence communities a rare chance to hear from massage workers, community organizers and artists who shared a variety of perspectives on human trafficking in the U.S. And for the last six years, the research cluster on race, medicine and social justice, led by Professor of Medical Studies and Africana Studies Lundy Braun, has investigated how fixed ideas about race impact the diagnosis and treatment of disease, causing doctors and researchers to ignore or underestimate social and environmental explanations for health disparities.

As a faculty fellow of the research cluster on mass incarceration and punishment, Associate Professor of Sociology Nicole Gonzalez Van Cleve has enlisted Brown students’ help to build the largest public archive of mass incarceration in the U.S. Founded in 2021 with seed funding from the Mellon Foundation and Brown’s Center for the Study of Race and Ethnicity in America, the Mass Incarceration Lab has grown into a collection of more than 200 accounts from people who are incarcerated and others who have felt the impact of mass incarceration.

Van Cleve explained that sharing incarcerated people’s stories brings more visibility to the links between historical slavery, anti-Black racism and crime and punishment in the U.S.

“Students in my undergraduate and graduate classes are taking great care to preserve the stories and powerful testimonies of so many people who have lived through and found life after incarceration,” Van Cleve said. “That act of preservation is important: It adds dimension and nuance to the story of incarceration in America, and it exposes the flaws inherent in our criminal justice system.”