PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — Past generations of Brown University students believed that setting foot inside the John Carter Brown Library was about as unlucky as passing through the Van Wickle Gates at times other than Convocation and Commencement.

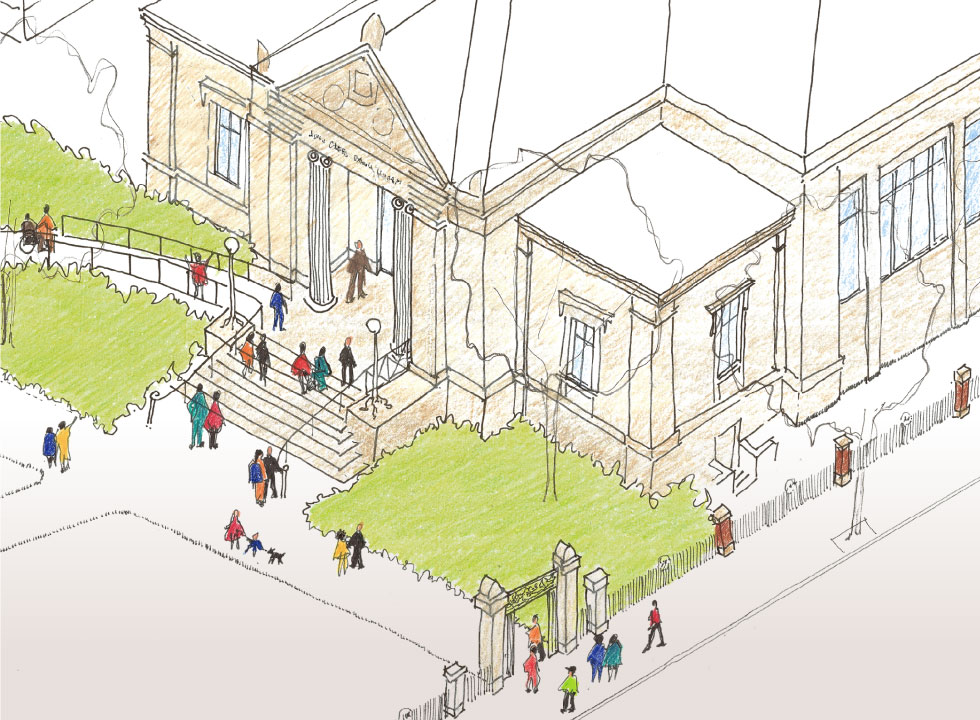

The JCB, an independent research library focused on the early colonial-era history of the Americas and located in the heart of the Brown campus, might have stoked that fear in students because of its imposing appearance. Entering the building once involved climbing steep limestone stairs, wrenching open two sets of heavy wooden doors and letting one’s eyes adjust to the dim interior.

But Karin Wulf, the JCB’s director and librarian, said she hopes recently completed renovations at the library — both physical and digital — will put those superstitions to rest once and for all.

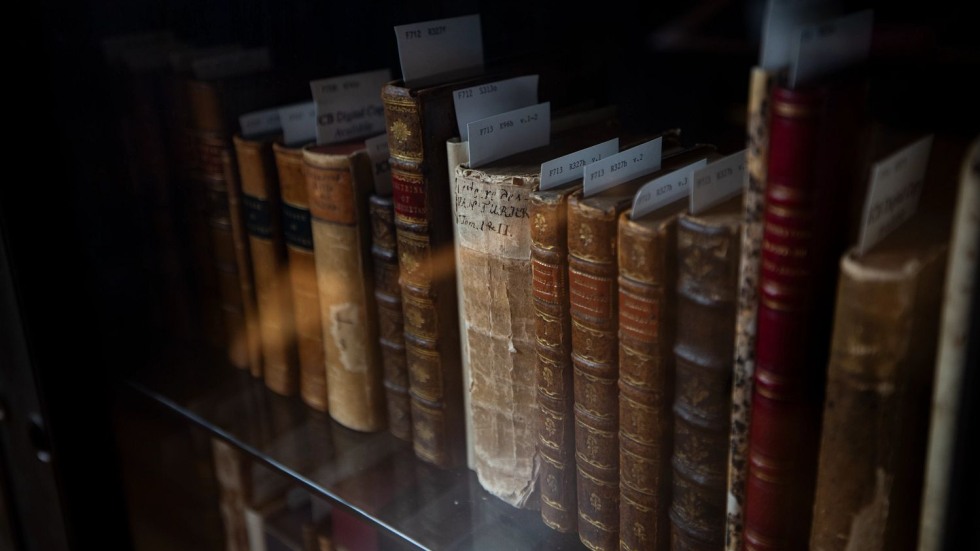

“The JCB has always welcomed all students, scholars and members of the public, but visually, the library may not have been sending that message,” said Wulf, who is also a professor of history at Brown. “We felt it was important to make the building and collections more transparent and accessible.”

Under Wulf’s leadership, and with robust support from its board, staff, supporters and Brown University — a close affiliate of the JCB — the library has invested in facilities improvements, designed new digital tools and curated new exhibitions, all in the name of expanding access to its resources and promoting inclusion.

Wulf said renovations to the building’s entrance on the College Green, finished in May, were subtle yet key to improving accessibility. In addition to the stairs, there’s now a paved ramp up to the entryway for wheelchair users and others with disabilities. Daytime visitors now enter the library via two sets of automatic glass doors, which let more light into the space and also allow passersby to see inside the library. (The exterior set of refurbished wooden doors remains, Wulf said, but they are propped open during visiting hours and close only at night.) And the windows inside the main library space have been cleaned and restored to their original state, further boosting the wood-paneled room’s natural light.

“Librarians tell me that researchers used to bring in book lights and lighted magnifying glasses just to be able to read some of the documents they were studying,” Wulf said. “By letting more light into this space, we’re not just making it a more pleasant place to be — we’re also literally making it more visually accessible.”