PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — This fall, the Watson Institute for International and Public Affairs at Brown University is exhibiting a series of nature-inspired prints by Rhode Island native Andrew Nixon, an artist and educator.

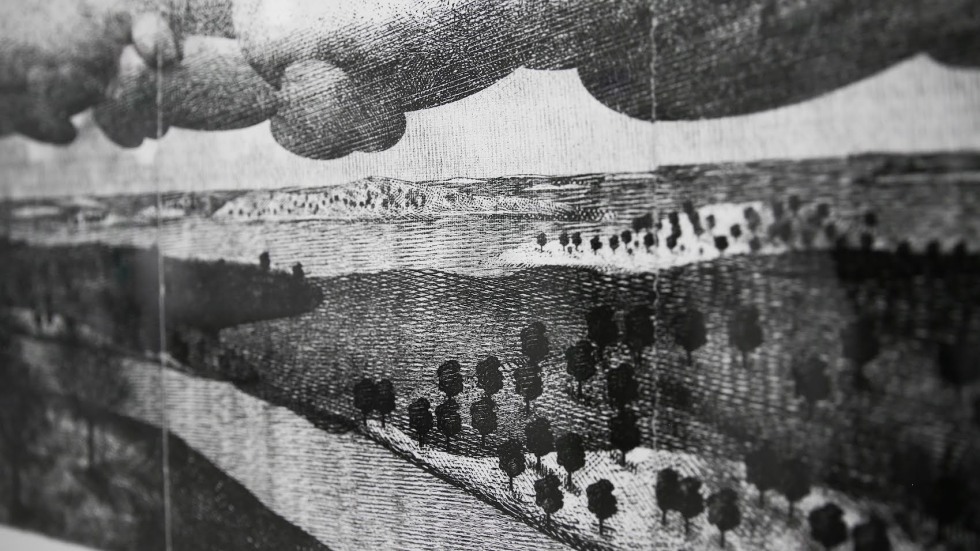

The exhibition, “Andrew Nixon: Inventions and Discoveries,” showcases 23 extraordinarily detailed natural landscapes, lively renderings of swimmers and fish and more. To make the prints, Nixon found creative ways to combine old and new artistic modes — using an iPad drawing application, an old-world etching technique and a printmaking practice that dates back to the 15th century.

Nixon’s prints are on display now through January on the first floor of Stephen Robert ’62 Hall at 280 Brook St. The Watson Institute will also host a talk and reception with Nixon on Tuesday, Sept. 26 at 5 p.m. in the True North Room inside Stephen Robert ’62 Hall. The exhibition is part of the Art at Watson initiative, which for a decade has integrated art into the fabric of the Watson Institute.

“These new works on paper were made using an innovative blend of old and new technologies,” Nixon said. “My images are initially generated through an iPad using a popular software program.” Then, he said, “the printing process I employ is the age-old traditional intaglio form, which requires the individual hand-inking of the plates. These are then covered with a dampened sheet of paper and run through a heavy steel press.”

From his studio in Massachusetts, Nixon is duplicating a process that was first established in Europe in the early 1400s. Historically used to make everything from playing cards to large-scale landscapes, intaglio printing is a slow, meticulous process in which an image is directly engraved onto a sheet of metal, covered in ink and a sheet of paper, and pressed. The United States Treasury still uses a dry intaglio technique to print paper money, because intaglio produces a level of fine detail that’s difficult to counterfeit.

Nixon said intaglio fell somewhat out of fashion when new technologies like photography surpassed the technique’s detailed image-making capabilities.

“Essentially, this limit was on the amount of data, specifically lines, that could be used to make an image,” he said. “Adding an iPad to the process rectifies this problem. By marrying the two technologies, I've found a way to think on a larger scale than was possible with traditional printmaking.”