PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — It took Nancy Hopkins, a pioneering cancer researcher, 20 years to accept that she was the subject of gender discrimination at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Even journalist Kate Zernike, who broke the story of MIT’s admission that Hopkins and other women faculty had faced discrimination on campus, took time to recognize that the story was big — it was 1999 and not 1959, Zernike thought, and her own career and her generation’s accomplishments were evidence of the ample opportunity available to women.

What shook Hopkins’ faith in the idea of meritocracy at her school was not meager lab space, male peers taking credit for her discoveries, or losing a popular course she had developed to a male faculty member. It was commiserating with another woman on the faculty, and then a dozen others, who’d had similar experiences.

And what struck Zernike was the way the women on campus described their unequal treatment:

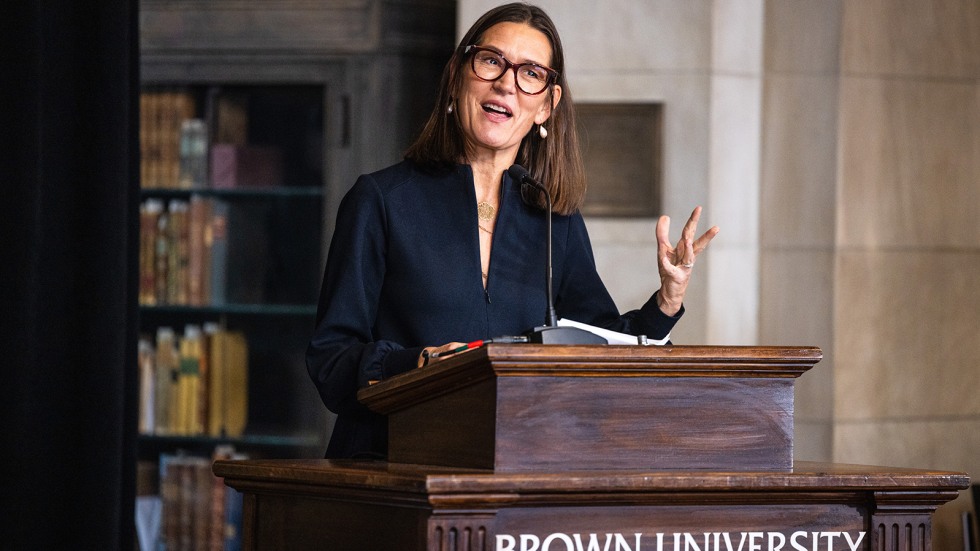

“It did not look like what they thought discrimination looked like,” Zernike said during an Oct. 17 event at Brown University. “It was less overt.”

The women called this “21st century discrimination,” Zernike said: a subtle and pernicious marginalization that ultimately accelerated. As young women in science, they were often treated well or even celebrated. But over time, as male counterparts were groomed for leadership positions and awarded prizes, women were frequently ignored and in the worst cases, pushed aside.

“Marginalization and lack of representation often happens unintentionally or unconsciously and sometimes despite the very best of intentions,” Zernike said.

The journalist came to Brown to tell the story of the fight for equal opportunity at MIT as a catalyst for a discussion about 21st century discrimination against women in the sciences, and what to do about it. She joined Carney Institute for Brain Science Director Diane Lipscombe, chair of Brown’s Task Force on the Status of Women Faculty, for a conversation moderated by President Christina H. Paxson at the John Carter Brown Library. The event was organized by the Office of the President and the Pembroke Center for Teaching and Research on Women.

Zernike described how her 1999 Boston Globe article about Hopkins and MIT went viral, through print and cable news, as women at other institutions and fields related to the group of vindicated scientists.

“The New York Times put the story on its front page that Tuesday and suddenly all the key players in this MIT story were flooded with emails from women around the country and around the world saying, ‘This is my story — and I thought I was the only one who felt this way,’” Zernike said.

While MIT’s president reacted by becoming a leader in efforts to get more women into science foundations and universities, hiring more women faculty and elevating women in leadership positions, that didn’t fix the problem, said Zernike, who expanded her article into a 2023 book titled, “The Exceptions: Nancy Hopkins, MIT, and the Fight for Women in Science.