PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — Parker VanValkenburgh has dedicated more than a decade of research to understanding how colonialism impacted Peru’s Indigenous people in the 16th century. That time marked a turning point in the region: Spanish forces conquered the Inca Empire, initiating a period of social violence and upheaval that included the forced resettlement of more than 2 million Indigenous people into a series of planned towns.

In the past, VanValkenburgh, an associate professor of anthropology at Brown University, led intensive archaeological survey and excavation projects to study the effects of these transformations on Indigenous peoples’ daily lives. He’d spend years focused on just one valley or site, studying post-colonization dietary changes by excavating pits filled with food waste.

VanValkenburgh believed that work was valuable, but he longed to zoom out — to see how his findings fit into, or differed from, other scientists’ findings across the region. So he partnered with Steven Wernke, an associate professor of anthropology at Vanderbilt University, to develop a tool that would map cultural and environmental change at a much larger scale.

The result is the Geospatial Platform for Andean Culture, History and Archaeology, or GeoPACHA — an open-source, browser-based platform that allows teams of researchers to work together to map archaeological sites in high-resolution satellite imagery.

“Archaeologists are really good at the small picture,” VanValkenburgh said. “We can dig into pits and tell you the minuscule ways in which the soil changed over time. But we lack the kinds of systematic data that we need to make sweeping statements about how those changes fit into the bigger picture of the growth of Indigenous societies in the past, of the Inca Empire’s rise and fall, and of the large-scale effects of Spanish colonization.”

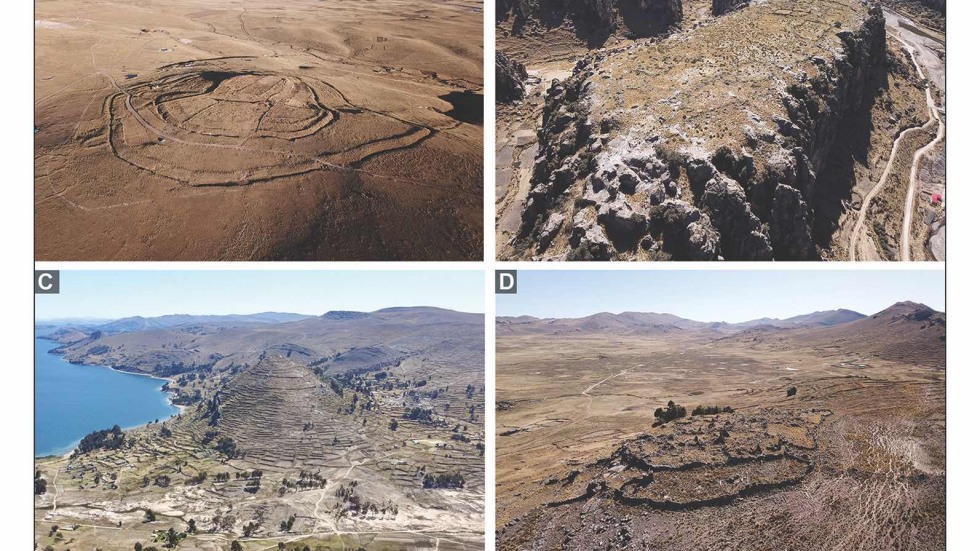

In collaboration with colleagues across the United States, Peru and several other countries, VanValkenburgh, Wernke and colleagues spent a year using GeoPACHA to gather data on ancient sites, roads, livestock corrals and agricultural terraces. Their work has yielded a raft of new findings about how Spanish colonization and forced resettlement changed the region’s population density, its natural landscape and in some cases even its climate.

The findings, detailed across six new papers, were published online on Monday, Dec. 18 in Antiquity. They’ll also be featured in the journal’s February 2024 print edition.