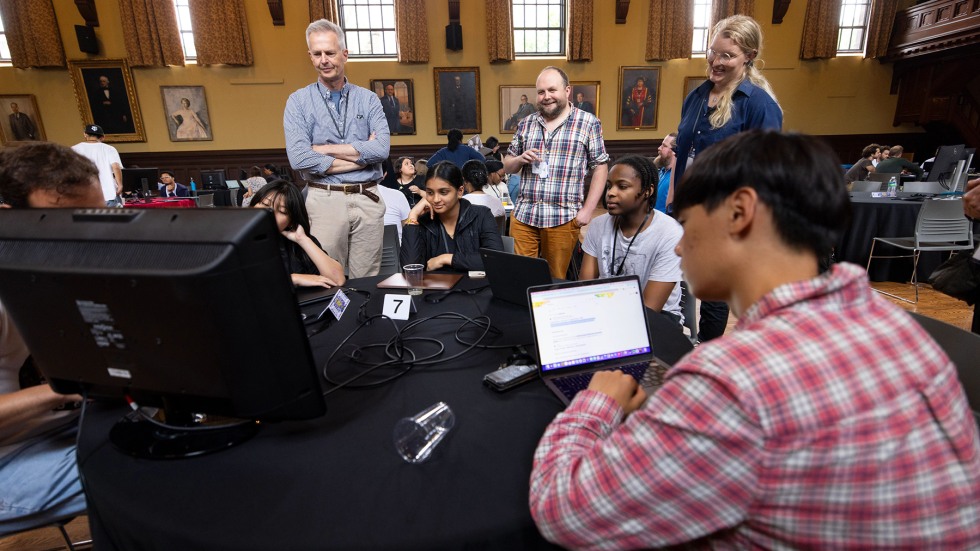

PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — Brown University’s Sayles Hall had been transformed into a computer lab: At round tables, teams huddled around monitors, scrolling through screens of numbers and graphs. Groups consisted of data scientists, clinicians, teachers and local high school students along with Brown master’s students and future physicians from its Warren Alpert Medical School.

The assignment was simple: Spot the biases hiding in the health data and create more equitable prediction models. But high school student Justin Hernandez described the organizers’ intentions in more ambitious terms:

“What they’re trying to do here is change the world,” said Hernandez, a sophomore at the Metropolitan Regional Career and Technical Center in Providence.

Ambitious, yes, but also on target, according to Brown faculty members Dr. Hamish Fraser and Dr. Jeremy Warner, hosts of the Brown University Health AI Systems Thinking for Equity Datathon. By creating collaborations among high school students, data scientists and clinicians, the datathon was intended to demonstrate that society needs people from diverse backgrounds to address bias in AI predictions, contribute to a more equitable health care system and mitigate future problems.

“Our goal is to educate people about bias in machine learning predictions and how that can impact every facet of our medical lives,” said Warner, a medicine and biostatistics professor.

To organize the event, Fraser and Warner collaborated with Kathryn Jessen Eller of the East Bay Educational Collaborative, one partner behind Data Science, AI and You in Health Care, a semester-long course that introduces local high school students to bias in machine learning (and how it can impact health care outcomes), critical data science, machine learning tools and skills to succeed in a data- and AI-oriented world.

The two-day datathon in early June was a culminating event for the 12 schools participating in the course this year, said Eller, who received funding for the program from the National Science Foundation and worked with science educators to create the curriculum for students with no prior statistics or coding knowledge.

Beyond expanding the students’ knowledge throughout the semester, the organizers also hoped that encouraging them to work with professionals at the datathon would increase their awareness of the role of data science in health care, and eventually contribute to broadening participation in the STEM workforce.

“During the datathon, students can see for themselves how truly dynamic data science can be, and experience how exciting and cutting edge this work is, how it’s associated with AI and machine learning, and how understanding data science in health care can improve diversity and create a better future for everyone,” Eller said. She added that after last year’s event, some students said that their experience inspired them to explore careers in data science and health care.

Digging into the data

The datathon at Brown was based on a model developed by Dr. Leo Celi, a scientist at Massachusetts Institute of Technology who, through the MIT Critical Data consortium, has organized over 50 global datathons built to encourage a collective of data scientists and medical experts to cooperatively solve health care problems. Celi developed Health AI Systems Thinking for Equity as a forum to analyze, discuss and mitigate unintentional bias within the data used during machine learning and generative AI to make health care decisions.

Gesturing around the buzzing hall at Brown, he praised the “hive learning strategy” of research: “We need everyone’s help, because the only way to regulate technology systems is to understand them,” Celi said. “In a datathon, everyone is a teacher, and everyone is a learner.”