PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — Over three seasons excavating reducciones, or colonial planned towns, in Peru, Parker VanValkenburgh and his international research team collected tens of thousands of small ceramic sherds. Those tiny pieces of pottery, dating back hundreds of years, could shed light on the lives and habits of the indigenous populations forcibly resettled into towns by Spanish colonialists — what they ate, how they organized their living spaces and how they were connected to the rest of the world.

In such an endeavor, critical mass is both a key and an obstacle.

“A single sherd on its own is often mute, but with 80,000 sherds you notice patterns and establish lines of evidence that enable you to tell really interesting stories,” said VanValkenburgh, an assistant professor of anthropology at Brown University.

In order to tell those stories, the sherds must be analyzed, described and recorded, a labor-intensive, time-consuming process. For his summer 2016 lab season, VanValkenburgh set out to develop an efficient recording method that would improve data integrity and meet the needs of his large, bilingual research team: a tablet-based software application with constrained fields and drop-down menus in English and Spanish.

Such an app could supplant the typical analysis and recording procedure, in which teams of researchers in a lab search through a thick paper “codebook” for up to 40 specific descriptive labels for each artifact and then enter each, individually, into a spreadsheet. A two-person team can enter data for about 40 artifacts in a day, VanValkenburgh said; if they were really efficient, they might log 100 items.

Needing a range of skills — including drawing, computer programming, user experience and product testing — and the perspective of an experienced archaeological field researcher who could test the module’s design, VanValkenburgh turned to a team of Brown undergraduates to make his idea a reality. He did so via an Interdisciplinary Team Undergraduate Teaching and Research Award, or I-Team UTRA, a program that diversifies research experiences by convening undergraduates from different fields for scholarly opportunities.

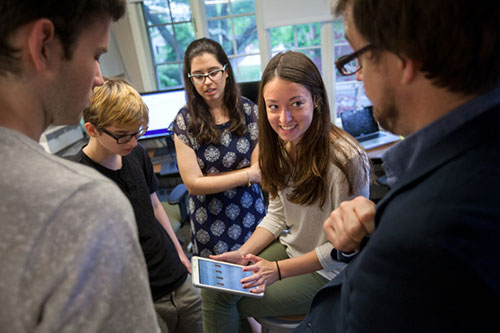

Last June, VanValkenburgh’s team — Chiara Repetti-Ludlow (linguistics and classics), Jackson Crook (computer science and linguistics), Luiza Silva (Egyptology and archaeology and the ancient world) and Jake Gardner (archaeology and anthropology) — joined forces in Providence to develop the module before heading to Lima, Peru, to test the app and use it for laboratory analysis.

After an intensive three-week period collaborating on the software, they created the Proyecto Arqueológico Zaña Colonial (PAZC) Ceramics module that, deployed in the lab in Lima, “increased efficiency of data entry by an average of about 20 percent,” VanValkenburgh said, and was found by the larger research team “to be universally more engaging than the conventional system we’d been using.”

Platform for collaboration

To create such an effective tool in less than a month required both skilled, focused students — VanValkenburgh described the group as “like a team of graduate students… really good graduate students” — and a platform from which to build their software.

The students used the Field Acquired Information Management Systems Project system developed by a history and archaeology professor at Macquarie University as the primary building block for their app. The open-source platform for digital data collection in the field can be used with Android devices to log written descriptions as well as upload photos, videos and audio records. It has been used by archaeologists, geochemists and others, but VanValkenburgh’s team was the first to customize the platform for artifact analysis.

Crook was the primary coder, and the team worked together to design a layout and organize data fields that would allow members of VanValkenburgh’s research team in Peru to deploy seven tablets in the lab and, ultimately, analyze 30,000 sherds over a six-week lab season over the summer.

Repetti-Ludlow took the lead on tracking module iterations and testing for efficiency and accuracy of data collection in a development process that VanValkenburgh described as intensely iterative, both in terms of layout and organization and in the sherd imagery that would help lab and field researchers avoid ambiguity in recording artifact types.

Silva and Gardner created images for the app, with Gardner drawing and redrawing versions of the sherds in Photoshop. While both had archaeological field experience (in Italy and Romania, respectively), neither was terribly familiar with New World ceramics.

“Having the opportunity to work on the artistic component of the module was very helpful in terms of situating me in this world,” said Silva, whose studies typically focus on Egypt. “I wouldn’t have known much about Inca and colonial ceramics had I not worked on this part of the project first.”

The students had to decide what pictures were and weren’t necessary based on what part and type of ceramic vessel the sherds originally came from, VanValkenburgh said. They had to constantly evaluate how effectively the drawings communicated what they needed to so researchers could correctly identify and log artifacts from the dig.

They also needed to create a truly bilingual program. VanValkenburgh said that for projects where a large, international and multilingual team with varied levels of experience manages artifact assessment, ensuring that language barriers and processing habits do not diminish data integrity is of great concern.

And the module itself, though created by native speakers of English, includes a translation file so that every element of it – every picture, button and field – has both an English and Spanish name, Repetti-Ludlow said.

Deploying the software

Once in Lima, the team started the season using the old system and then transitioned to the module so everyone would have experience with both systems.

“We found that when we switched to the module, it clarified many aspects of classifying artifacts, like what certain decorations look like and how surface condition is recorded,” Repetti-Ludlow said. “Another unanticipated success was its overwhelming popularity. Users unanimously preferred using the module to the old system according to an anonymous survey we conducted at the end of the season. Although there are a few minor tweaks we plan on making, the system was overall hugely successful in terms of speeding up classification, helping with accuracy, clarifying the classification process and maintaining interest.”

This was the kind of success VanValkenburgh had hoped for when he proposed the I-Team UTRA last year.

“I’m particularly thankful to have received the funding from this truly innovative program,” VanValkenburgh said. “I do not possess the full range of skills and knowledge required to build such a tool by myself,” but by mentoring and supporting a committed, interdisciplinary group of students and treating them “as full scientific partners,” he said, the group was able to find a novel solution to a longstanding challenge in the field.

Oludurotimi Adetunji, associate dean for undergraduate research and inclusive science at Brown, said that the team’s project “epitomizes the goals of the I-Team UTRA. It engages students from diverse academic backgrounds… and exceeded the goals described in their I-Team UTRA proposal.”

The team is currently finalizing data analysis, VanValkenburgh said, and drafting a paper that they will be submitting to a peer-reviewed journal by the end of the fall semester.

“We want to share not just the discussion but the code itself,” VanValkenburgh said, “and maybe make it open source. It’s important to be generous and magnify the impact of the work you do.”