PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — Typically, when a new collection at Brown University’s Pembroke Center archives is made accessible to researchers, requests to view the materials trickle in gradually.

But in November 2019, when the Pembroke Center for Teaching and Research on Women announced that the papers of Hortense J. Spillers — one of the most significant black feminist scholars of the late 20th century — were available, the center’s staff faced an immediate flood of inquiries from all over the world.

“We were inundated,” said Mary Murphy, the Nancy L. Buc ’65 Pembroke Center Archivist. “There was a huge response just to the announcement that the collection was available and at Brown.”

Members of the public, faculty and students from Brown and universities across the country, and researchers from Hungary to South Africa asked for access to the papers and personal materials of Spillers, who continues to teach English at Vanderbilt University.

Social media posts about the Spillers papers went viral. Researchers walked into Brown’s John Hay Library asking for the Spillers papers, some simply presenting the Twitter thread at the front desk. Murphy and Amanda Knox, the Pembroke Center’s assistant archivist, began fielding research requests before they had a chance to transfer the collection to the John Hay Library, where Pembroke Center archive collections are normally housed — so they reorganized their office to make space for visiting researchers.

Why the intense interest in Spillers’ papers?

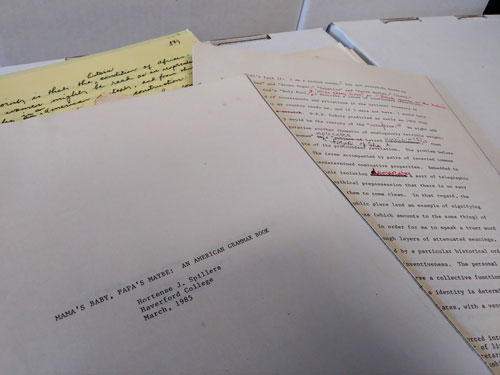

“Hortense J. Spillers has been a foundational figure and a critical voice in feminist theory, as well as American, African American and Caribbean literary and historical, cultural and philosophical studies since the 1970s,” said Ann duCille, a visiting scholar in gender studies at the Pembroke Center who worked closely with Murphy to bring the papers to Brown. “From early essays like ‘Interstices: A Small Drama of Words,’ to landmark interventions such as ‘Mama’s Baby, Papa’s Maybe: An American Grammar Book,’ Spillers’ scholarship has played — and continues to play — a major role in how we theorize race, class, gender and sexuality, how we read history and write literature and criticism, and how we understand the long reach of slavery and its legacies.”

The papers in Spillers’ collection date from 1966 to 1995. Included are diaries; unpublished writing, including fiction and poetry; correspondence with prominent scholars, including Gwendolyn Brooks, Henry Louis Gates Jr. and Toni Morrison; and drafts of her talks, articles and books. Researchers can also find syllabi, lecture notes, scholarly journals, some rare print materials and notes on Spillers’ experience in higher education.

Murphy said that already, the papers are being used by scholars working in American studies, English, Africana studies, gender and sexuality studies and myriad other disciplines.

“To me, Spillers works to understand black consciousness,” said Kevin Quashie, a professor of English at Brown who is leading a Spring 2020 seminar focused in part on Spillers’ work and legacy. “By consciousness, I don't mean awareness, anything that we control. I don't mean the idea of political intentionality. I mean consciousness as a feature of the human, how the human experiences their aliveness, their being human.”

Knox, who organized and catalogued the collection, describes the papers as straightforward but poetic in nature. Spillers presents engaging thoughts on the first “Star Wars” movie, a play written by Toni Morrison and the assassination of Robert F. Kennedy.

“Not just academics can access and pull meaning from this collection,” Knox said. “Really, anybody can.”