PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — With COVID-19 impacting communities across the world, 2020 has been a volatile year for medical and public health professionals — undoubtedly an interesting, challenging time to lead a global health institute. Or to take the helm of a public health school at a major research university.

Dr. Ashish K. Jha has done both — culminating a successful term as faculty director of the Harvard Global Health Institute to become the next dean of the Brown University School of Public Health on Sept. 1.

The accomplished physician, health policy researcher and global health advocate has also advised mayors, governors and members of Congress on pandemic response; offered advice to academic leaders at Brown and other schools on plans for 2020-21 operations; and contributed his expertise to the public through near daily appearances with local, national and global news outlets.

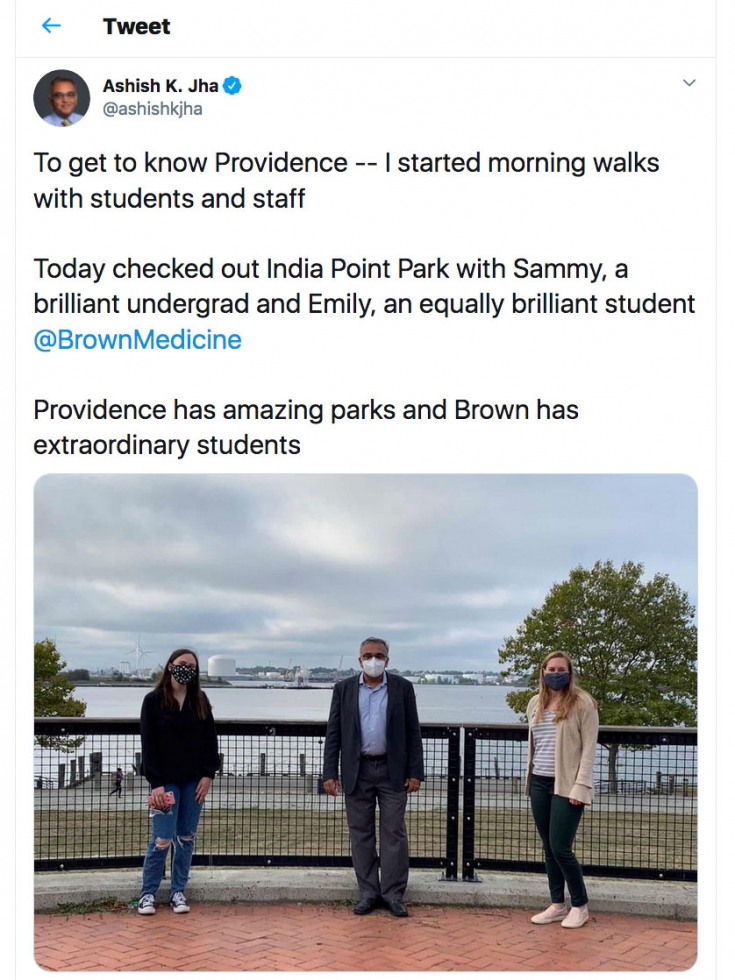

Twice a week, he’s also walking the streets of Providence with students, faculty and staff from the Brown community — appropriately masked and social-distanced — learning on the fly about the University, its host city and the individuals who will be his colleagues for the years to come.

One month into his tenure as dean, Jha shared insights on what brought him to Brown, what the COVID-19 pandemic will teach future public health professionals about leadership, and why Brown’s School of Public Health is poised to become a global leader in research and education.

Q: Before we frame everything through the lens of COVID-19, tell us why you chose to come to Brown.

Public health is a field that does best when it is truly multidisciplinary — the problems we're trying to solve don't always lend themselves perfectly to any single discipline. There are many disciplines that are very, very important — economics, sociology, anthropology, humanities. But if you look at public health through any one lens, you do not see the complexity of the whole thing.

What I got excited about when I learned about the Brown University School of Public Health was — obviously it's a great school, but also one established within the broader context of the University. Brown is a place more inherently multidisciplinary in its structure and culture than almost any other university I've encountered. That struck me as the right environment to grow a public health school and see it flourish in tackling the big issues.

Q: Brown announced your appointment on Feb. 26, 2020 — what understanding did you have then that COVID-19 would impact the U.S. to the degree that it has?

By the end of January, we were aware that this virus was within our shores. But I felt confident that we were going to take a really effective set of public health steps to manage the disease. I even wrote that I thought America's response was going to be quite good — we have great public health agencies, and we have the CDC.

By late February, I was concerned because I expected to see a series of actions by the federal government that I wasn't seeing. I could not believe that our country had wasted six weeks and not prepared. I assumed that preparations were happening, testing was being built out — that our country was getting ready and that somehow I was just missing it.

It was right around that announcement that it dawned on me that we, as a nation — and really the federal government — had missed an incredible opportunity. I went from concerned to downright distressed as it became clear that we were about to get hit pretty hard.