PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — Planetary scientists from Brown University have developed a new remote sensing method for studying olivine, a mineral that could help scientists understand the early evolution of the Moon, Mars and other planetary bodies.

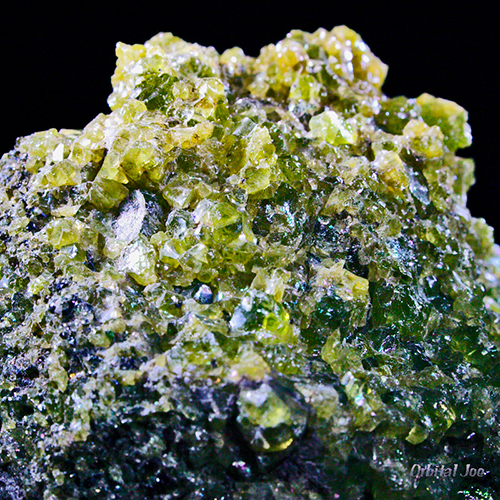

“Olivine is understood to be a major component in the interiors of rocky planets,” said Christopher Kremer, a Ph.D. candidate at Brown University and lead author of a new paper describing the work. “It’s a primary constituent of Earth’s mantle, and it’s been detected on the surfaces of the Moon and Mars in volcanic deposits or in impact craters that bring up material from the subsurface.”

Current remote sensing techniques are good at spotting olivine from orbit, Kremer says, but scientists would like to do more than just spot it. They’d like to be able to learn more about its chemical makeup. All olivines have silicon and oxygen, but some are rich in iron while others have lots of magnesium.

“The composition tells us something about the environment in which the minerals formed, particularly the temperature,” Kremer said. “Higher temperatures during formation yield more magnesium, while lower temperatures yield more iron. Being able to tease out those compositions could tell us something about how the interiors of these planetary bodies have evolved since their formation.”

To find out if there might be a way to see that composition using remote sensing, Kremer worked with Brown professors Carlé Pieters and Jack Mustard, as well as mountains of data from the Keck/NASA Reflectance Experiment Laboratory (RELAB), which is housed at Brown.

One method researchers use to study rocks on other planetary bodies is spectroscopy. Particular elements or compounds reflect or absorb different wavelengths of light to various degrees. By looking at the light spectra rocks reflect, scientists can get an idea of what compounds are present. RELAB makes high-precision spectral measurements of samples for which the composition is already determined using other laboratory techniques. By doing that, the lab provides a ground truth for interpreting spectral measurements taken by spacecraft looking at other planetary bodies.

In poring through data from olivine samples examined over the years at RELAB, Kremer found something interesting hiding in a small swath of wavelengths that’s overlooked by the kinds of spectroscopes that fly on orbital spacecraft.

“Over the past few decades, there’s been a lot of interest in near infrared spectroscopy and middle infrared spectroscopy,” Kremer said. “But there’s a small range of wavelengths between those two that’s left out, and those are the wavelengths I was looking at.”

Kremer found that those wavelengths, a band between 4 and 8 microns, could predict the amount of magnesium or iron in an olivine sample to within about 10% of the actual content. That’s far better than can be done when those wavelengths are ignored.

“With the instruments we have now, we could say maybe we have a little bit of this or a little bit of that,” Mustard said. “But with this we’re able to really put a number on it, which is a big step forward.”

The researchers hope that this study, which is published in Geophysical Research Letters, might provide the impetus to build and fly a spectrometer that captures these previously overlooked wavelengths. Such an instrument could pay immediate dividends in understanding the nature of olivine deposits on the Moon’s surface, Kremer says.

“The olivine samples brought back during the Apollo program that we’ve been able to study here on Earth vary widely in magnesium composition,” Kremer said. “But we don’t know how those differing compositions are distributed on the Moon itself, because we can’t see those compositions spectroscopically. That’s where this new technique comes in. If we could figure out a pattern to how those deposits are distributed, it could tell us something about the early evolution of the Moon.”

There’s the potential for other discoveries as well. The airplane-based SOFIA telescope is one of the few non-lab instruments that can look in this forgotten frequency range. The instrument’s recent detection of water molecules in sunlit lunar surfaces made use of those frequencies.

“That makes the idea of space-borne spectrometers that can see this range much more attractive, both for water and for rocky material like olivine,” Kremer said.

The research was supported through NASA SSERVI (NNA14AB01A) and a NASA FINESST grant.