PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — On a chilly November afternoon, a handful of undergraduate students at Brown University gathered in a cozy, casual lounge to dig into the particulars of the Hawaiian language.

Why, one student asked, does the Hawaiian equivalent of “get in the car” sound more like “get on the car”?

Because, Makana Kushi explained, the phrase was developed to refer to a very different kind of vehicle.

“In Hawaiian, it’s more like ‘getting onto a car’ because it came from the way Hawaiians would talk about launching a canoe on the water,” Kushi said.

Despite a wide range of language courses offered at Brown, Hawaiian isn’t an official class listed in the catalog. Neither is Navajo, Narragansett or Yoruba. Yet during the Fall 2021 semester, 20 students at the University have met weekly to learn one of 10 global Indigenous languages, including those four, for academic credit.

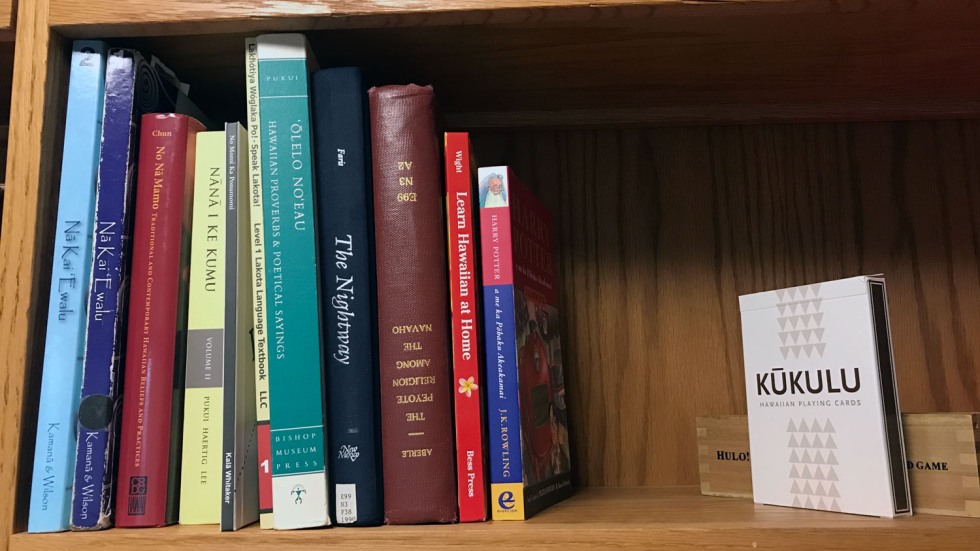

That experience has been made possible by Kushi, a Ph.D. student in American studies and a program coordinator for Brown’s Native American and Indigenous Studies Initiative. This semester, Kushi has served as the advisor for a Departmental Independent Study Project, a mechanism by which Brown undergraduates can initiate, design and execute a course of their own with the help of a faculty member or instructor.

The project isn’t just allowing Brown’s Indigenous students to deepen connections with their respective ancestral heritages and introducing those from other backgrounds to these languages. It is also helping to keep Indigenous languages, and thus Indigenous cultures, alive at a time when many are under threat.

“Semester after semester, students would come up to me and ask if there was a way for them to study their native languages and get credit for it,” Kushi said. “It’s something a lot of students have tried to do in their spare time for years, only to have classes and social commitments undercut their efforts. They are all interested in preserving these languages for the sake of their communities, and they wanted a way to stay accountable.”