PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — Motivated to be closer to family, John Wilner and his girlfriend relocated from San Francisco to Providence in 2017. It was late June when the new homeowners settled into the city's Silver Lake neighborhood, he recalled, and Fourth of July celebrations were beginning in earnest.

"As soon as we got here, the fireworks season started," Wilner said. "We were surprised by how long the fireworks would go, and by how late."

As longtime residents of major cities, the couple dismissed the nightly fireworks initially but soon found that the city’s excessive noise levels — from constant rumbling of road traffic, daily blaring of gas-powered leaf blowers, jarring bursts of construction machinery and at-times over-amplified music from area restaurants, bars and night clubs — weren't an isolated occurrence.

Through talks with neighbors, Wilner learned that the disturbances were causing unrest and distress to hundreds of Providence community members, and that formal complaints and calls to city officials would often go unanswered.

So he and other city residents took matters into their own hands.

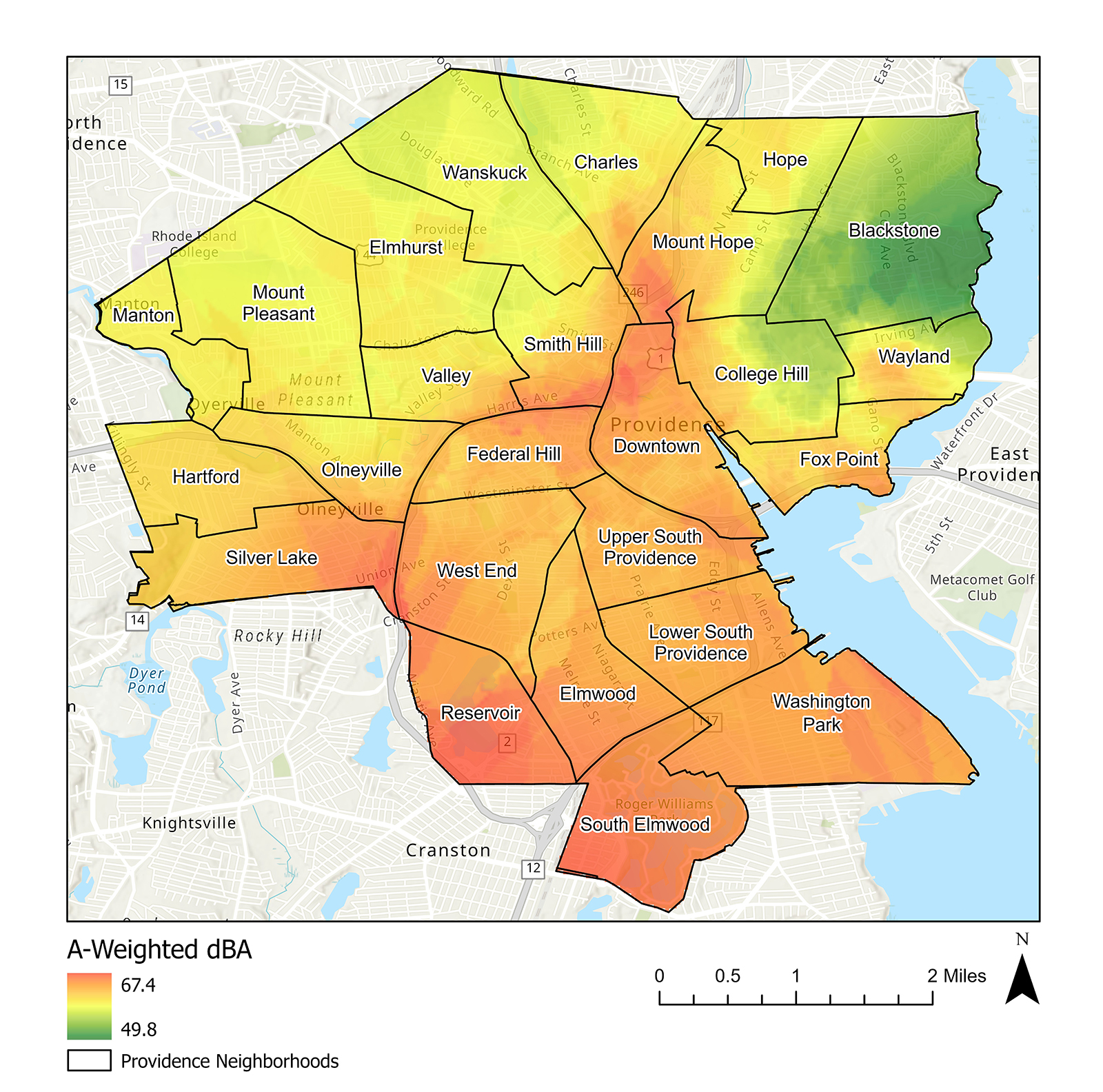

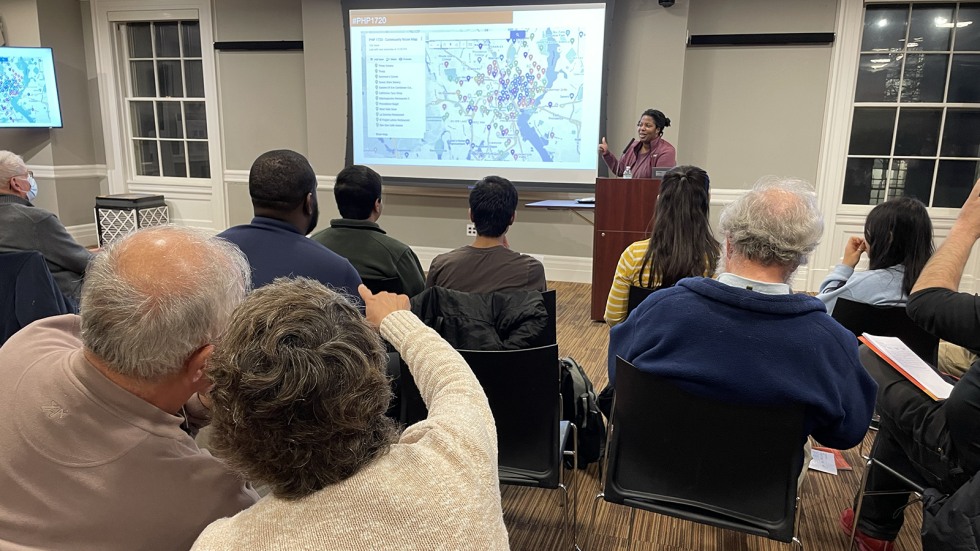

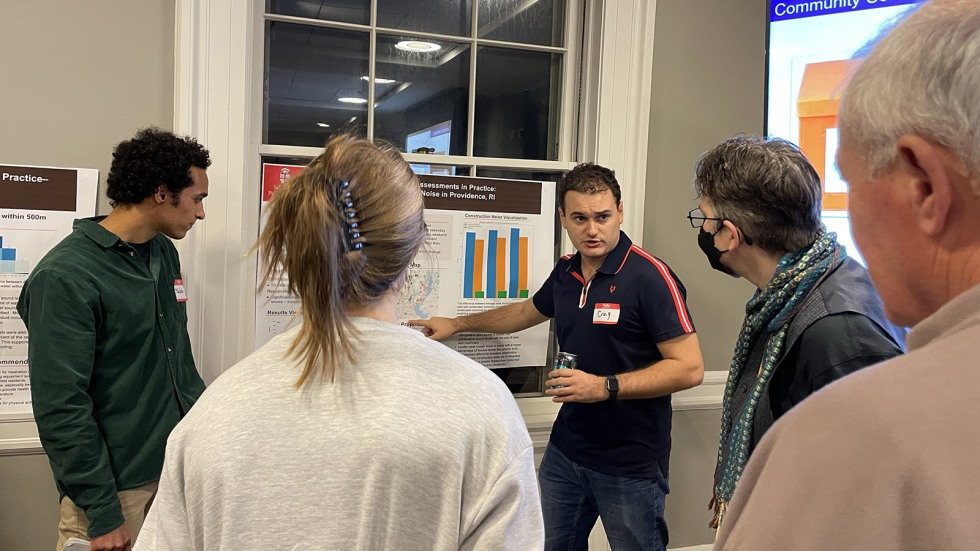

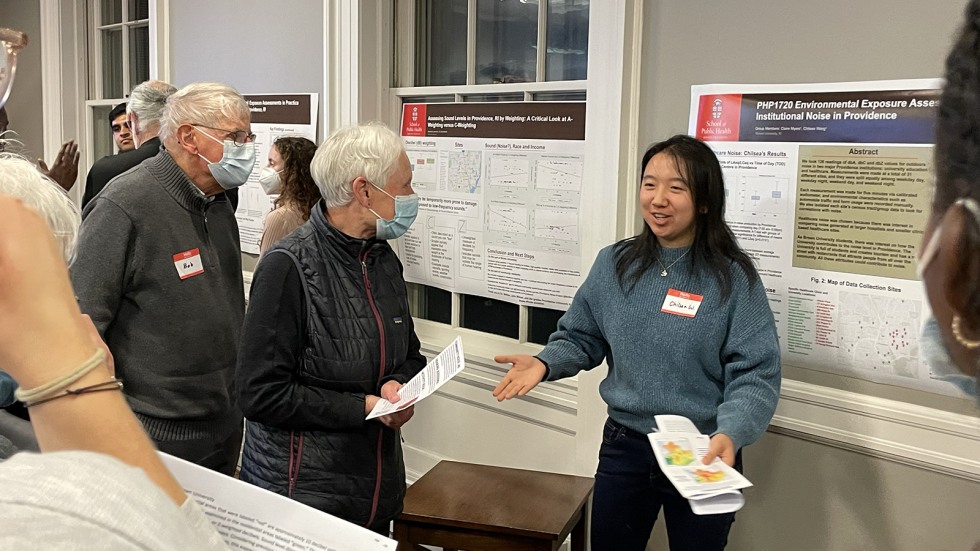

To advocate for long-term noise reduction solutions that could improve health and quality of life for local residents, they formed the Providence Noise Project. While the volunteer group collects daily noise disruptions through a Community Noise Survey and outreach, their advocacy work requires impartial proof of just how loud it can be to live in the city. For that, they partnered with the Community Noise Lab at Brown University to capture new data that shows noise levels in city neighborhoods.

"The first step to bringing change is to acknowledge that there is a problem," Wilner said. "We wanted to figure out a way to see how loud the city really is, and the data will set that baseline."