PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — When competitive boxer Hannah Doyle throws punches in the ring, she knows precisely what her brain is doing to enable her body to string together sequences like jab, cross, hook, cross — and other winning combinations.

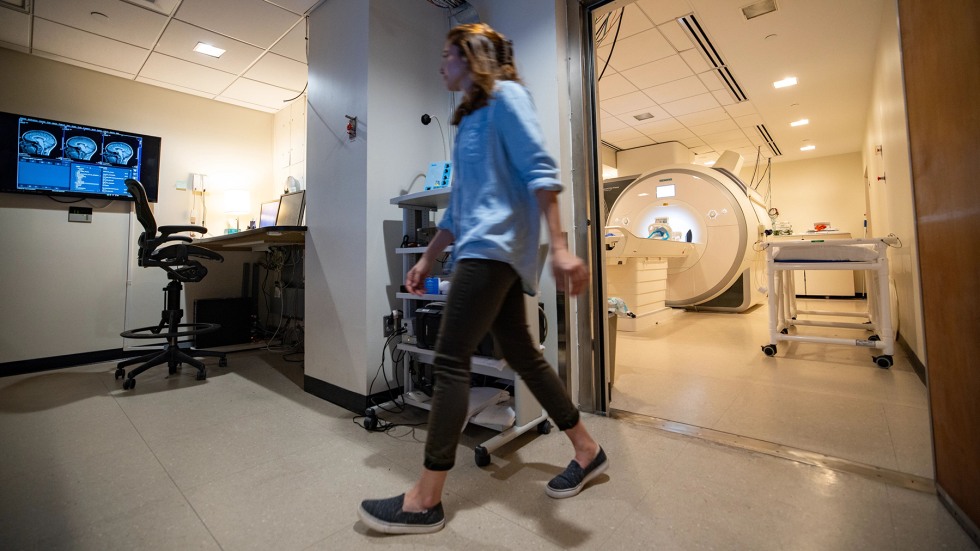

That’s because as a fourth-year neuroscience Ph.D. student at Brown University, Doyle studies cognitive control mechanisms and sequential processing — which just happens to relate to what has become her favorite hobby.

Doyle discovered boxing during the COVID-19 pandemic while looking for gyms offering challenging classes and connections with other people. She found both at Elite Boxing and Fitness in North Attleboro, Massachusetts, where she also met coaches who instructed her in the technical aspects of boxing.

The sequences, in particular, captured her interest.

“I liked how choreographed boxing seems,” Doyle said, “especially at the beginning when I was learning combinations and figuring out how to string together combinations of offensive and defensive moves. I really enjoyed feeling like I could nail down a specific combination of moves."

Doyle has competed in six fights, with four wins. Early in 2023, she competed in the Southern New England Golden Gloves amateur boxing tournament and won the sub-novice division finals. She’ll return to the annual tournament in January, where she’s excited to compete in the novice division.

While boxing offers a break from the intensity of lab work, Doyle appreciates how the two are related. Neurologically speaking, a combination like jab, cross, hook, cross would be classified as a purely motor sequence, in which the individual steps in the sequence matter, she explains. She practices purely motor sequences as part of her training to help her learn technique and gain muscle memory.