PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — In 2019, historian Lukas Rieppel published a book about the history of dinosaur fossils and their excavation in the late 1800s to create museum displays.

But an entire facet of the story didn’t make it into the book, the Brown University associate professor of history said, because he couldn’t do it justice at the time. Rieppel wondered about the ways that Native people in North America thought about fossils before non-Native scientists showed up on fact-finding and excavation missions.

With support from a Mellon Foundation grant, Rieppel has devoted the last two-plus years addressing precisely that question. He has been studying the history of the White River Badlands in South Dakota and Nebraska in partnership with Craig Howe, a citizen of the Oglala Sioux Tribe who grew up in the Pine Ridge Reservation and founded the Center for American Indian Research and Native Studies there.

“I wanted to focus on a specific place and a particular group of people,” said Rieppel, who joined the Brown faculty in 2013. “And I knew that it was important to collaborate with Native people who live in the area, so working with Craig has been a wonderful opportunity.”

Through a series of trips, Rieppel spent nearly a year at the Pine Ridge Reservation, which is one of the largest Native reservations in the U.S. In addition to working with Howe, his time there included getting to know the land by hiking with a knowledgeable guide in the White River Badlands and working with the Woksape Tipi Library and Archives at Oglala Lakota College in Kyle, South Dakota.

The extensive collaborations and research culminated in a scientific commentary, “Why museums should repatriate fossils,” published in Nature; an interactive digital map tracing an 1874 expedition in the Black Hills led by George Armstrong Custer; and a series of columns in Pine Ridge’s weekly newspaper, the Lakota Times, which aim to make the research accessible to a wider audience.

Multiple Brown students have contributed to the project, including Audrey Wijono, a senior history concentrator who helped with the digital map creation this summer. Wijono and other students worked with archival materials, including journals, newspapers and firsthand accounts, to describe what happened on each day of Custer’s expedition.

“I appreciated how this experience underlined the importance of rereading colonial histories for Indigenous experiences, and the importance of making these histories publicly available,” Wijono said.

Howe, who has a Ph.D. in architecture and anthropology, said he has valued the opportunity to produce work that centers Lakotan history and culture within the broader context of 19th-century U.S. history.

“What our research center has been pushing back against for 20 years is anti-intellectualism dealing with American Indian thought and philosophy, and so we approach these narratives with critical intentionality,” Howe said. “Our academic training gives us a grounding and a way to talk about these things that can be supported with evidence.”

Uncovering untold stories from historic expeditions

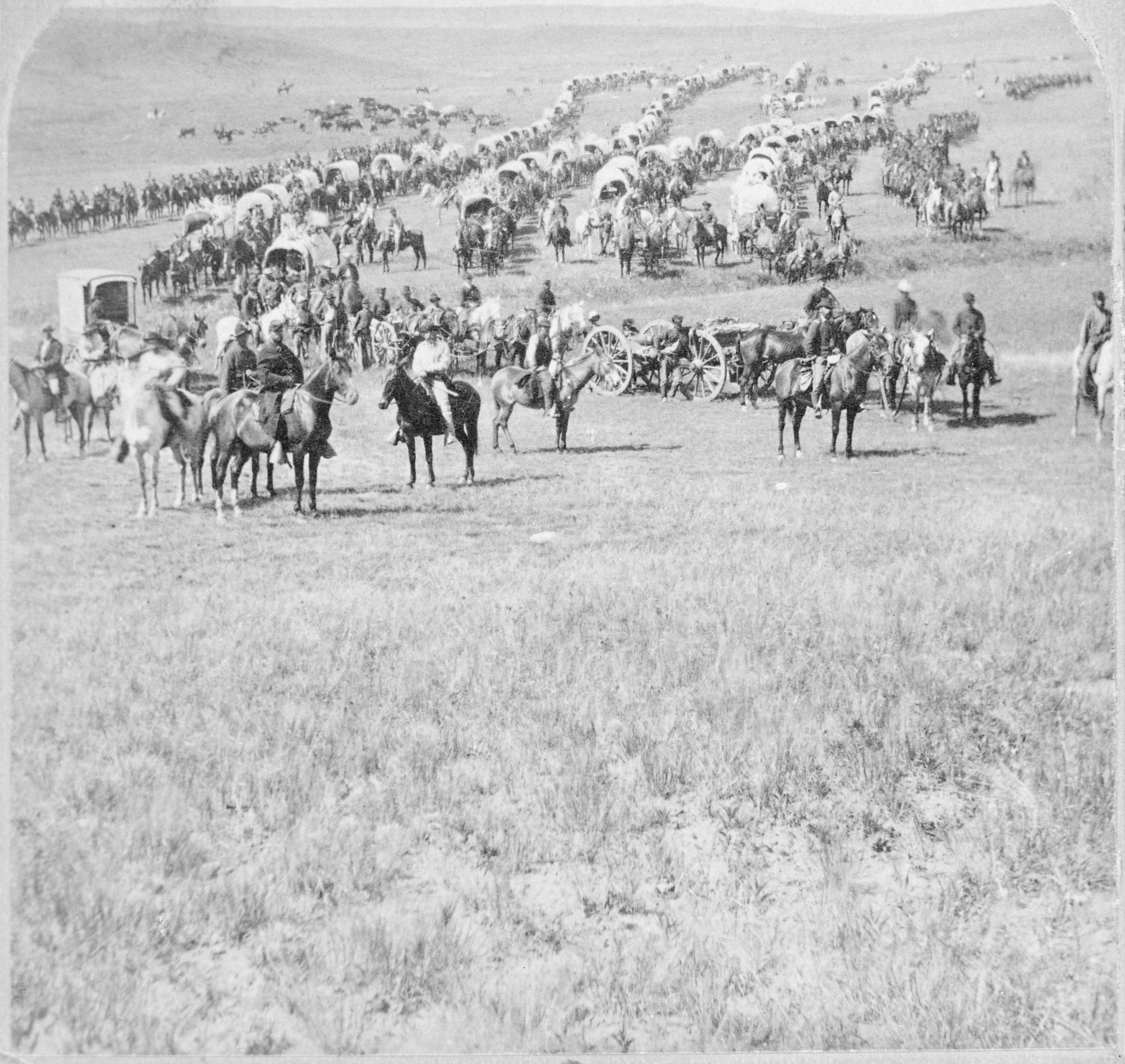

For the Nature commentary, Howe and Rieppel researched two expeditions that took place during the summer of 1874 — only six years after the Treaty of Fort Laramie was signed, wherein the United States formally recognized Lakotan sovereignty in a region about the size of Spain. The first and more prominent expedition consisted of more than 1,000 heavily armed troops led by Custer and included scientists whose job was to document the area’s rich geological resources. The second occurred later that year, when — according to the pair’s research — Yale University paleontologist Othniel Charles Marsh dug up two tons of prehistoric fossils without permission from the Lakotan people and transported them to New Haven, Connecticut.

“When [Marsh] shipped the fossils to Connecticut, most of the Lakotan meanings and stories tied to them were stripped away,” Howe and Rieppel wrote in the article. “Perhaps most egregiously, Marsh’s specimens were subsequently used to support an erroneous, racist theory of evolutionary progress that was deployed to justify the imperial expansion of the United States.”

In the article, Rieppel and Howe urge natural history museums to research their ties to extractive colonial practices and invest in repairing their relationships with Native tribes.

“The 1868 Treaty of Fort Laramie — which, according to a 1980 ruling by the U.S. Supreme Court, remains in effect — explicitly sets aside the lands around the Black Hills for the ‘absolute and undisturbed use and occupation’ of Lakotan people,” Howe and Rieppel wrote. “Why should this language not cover the extraction of specimens?”

To broaden public access to their scholarship, Rieppel and Howe collaborated with Brown’s Center for Digital Scholarship to design an interactive digital map of Custer’s expedition. Titled “In and Out of Place: Resource Extractions from Treaty Lands,” the map was developed by the center's staff and is rich with historical details and archival photos. Students like Wijono have worked on the project with the support of Brown’s Undergraduate Teaching and Research Awards program, which funds student and faculty collaborations.

“By mining the rich archive of primary source material for information about the region’s Native inhabitants, the project is turning the extractive goals of the expeditions back on themselves,” Rieppel said.

Another key component of Howe and Rieppel’s project is a series of weekly Lakota Times columns, which describe what Custer’s expedition reveals about Lakotan history and culture. The series was published in the Lakota Times from July to September 2024. The final column focused on how Lakotan people responded to the expedition by trying to engage the United States using diplomacy — which contrasted starkly with the behavior of expedition soldiers, the researchers found.

“Lakotans knew what was going on in their treaty lands,” Howe and Rieppel wrote. “They did not like what they saw, but they still tried to honor their treaty. For that, they were met with deception and violence.”

A $280,000 New Directions Fellowship from the Mellon Foundation funded the multi-year research project, and Rieppel and Howe said they are committed to continuing their work. They are currently exploring the creation of a museum exhibit of extracted fossils within the treaty lands.

“I’m incredibly grateful to everyone who has taken time to share their knowledge and experience,” Rieppel said. “It’s important that the intellectual property created from these projects stay in the treaty lands, just like the fossils should go back to the treaty lands.”