PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — A year after debuting his three-dimensional light installation in Brown University’s Lindemann Performing Arts Center, award-winning artist Leo Villareal returned to campus for a two-day symposium during which he reflected on his immersive public artwork at Brown and the ways it has added a new dimension to his overall body of work.

Villareal’s “Infinite Composition” adorns 30 structural columns with illuminated panels of white LEDs that flow in an endless variety of patterns in the Nelson Atwater Lobby of The Lindemann, which opened in Fall 2023 in the University’s Perelman Arts District. The installation is viewable from the street and adjacent campus spaces, inviting community members into the creative activity of the building.

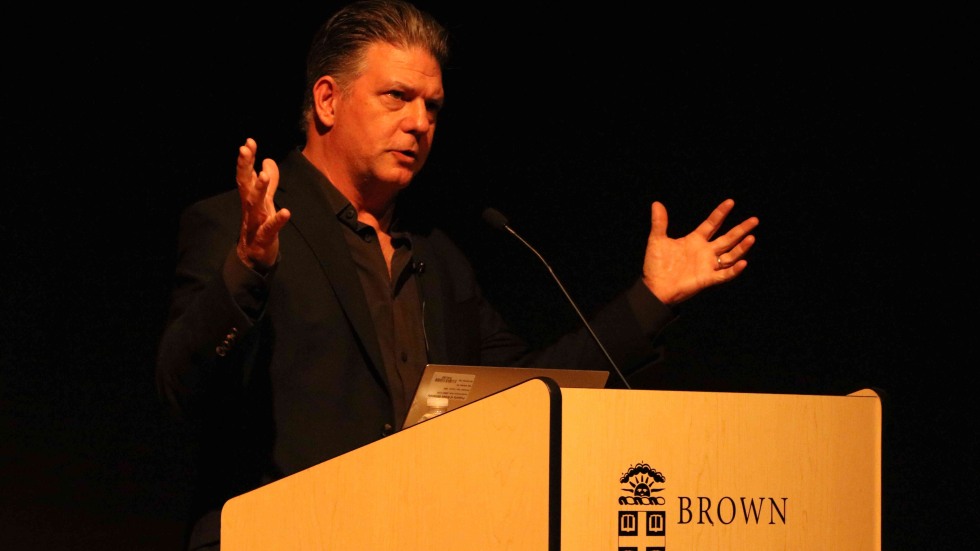

Villareal said the installation is in some ways a departure from his other public artworks, which include iconic pieces such as “The Bay Lights,” which illuminated nearly two miles of the San Francisco-Oakland Bay Bridge for 10 years and is set to return next year, and the “Multiverse” installation in the National Gallery of Art in Washington.

“For me, this is a very new type of piece,” Villareal said. “I’ve made a lot of volumetric pieces using LED strips, but usually those are long strips, and they have a single channel of LED, and it’s not the resolution that these columns have. This is really the first time I’ve done something like this, which is volumetric, and you can sort of be inside the artwork.”

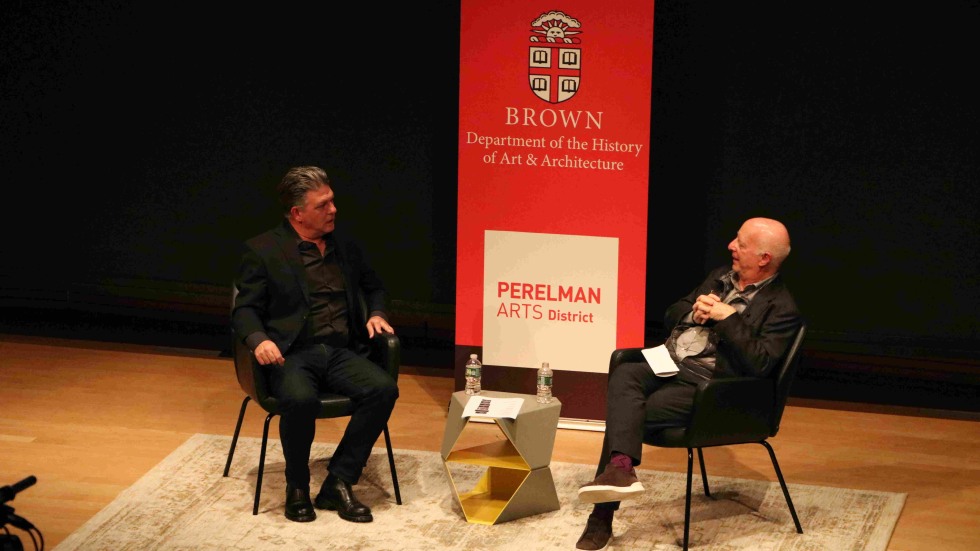

Villareal spoke at Brown on Friday, Sept. 27, during the first day of the Light in Art and Architecture Symposium, which featured artist panels, roundtable discussions, a tour and other events in celebration of Villareal's luminous installation. The symposium was presented by the Department of the History of Art and Architecture as part of the Brown Arts Institute’s IGNITE series.

During a presentation and wide-ranging discussion with noted architecture critic Paul Goldberger, Villareal reflected on his youth, his creative process and the story behind his most noteworthy works, including “Illuminated River,” a long-term illumination of several bridges over the Thames in London.

Villareal said that some aspects of his creative process require precise planning and thought, while others emerge from moment to moment, as was the case with “Infinite Composition.”

“When [I was] making this work, it [was] very improvisational,” Villareal said. “I’m trying things out, and I’m interested in concepts of emergent behavior and artificial life, meaning that you don’t necessarily know what the result is going to be — you try something and wait for those moments of surprise to occur.”