PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — In 2017, photographer Daniel Farber Huang traveled to the Greek island of Chios, off the coast of Turkey, where thousands of refugees had arrived after fleeing war in Syria.

Huang visited a refugee camp, and to his surprise, many people he met asked him to take their photo when they spotted the camera around his neck, even though most had cameras on their own mobile phones.

“When Daniel got home, we tried to understand why so many refugees had asked him — a complete stranger — to take their photos, and we realized it could be validating in a certain way,” said Huang’s wife and photography partner, Theresa Menders. “It was a symbol that somebody recognized them as having survived.”

With the intention of making more portraits, Menders joined her husband on a return trip to Chios a few months later. Understanding the power of a photo for those who had lost so much, they set up makeshift studios that included portable printers powered by generators so they could give their subjects high-quality copies of their portraits. Since then, the couple, who live in West Greenwich, Rhode Island, has documented and distributed thousands of printed photos at several other refugee camps around the world.

“Having a physical photo of family or friends to hold in one’s hands can be a great comfort in times of need,” Huang said.

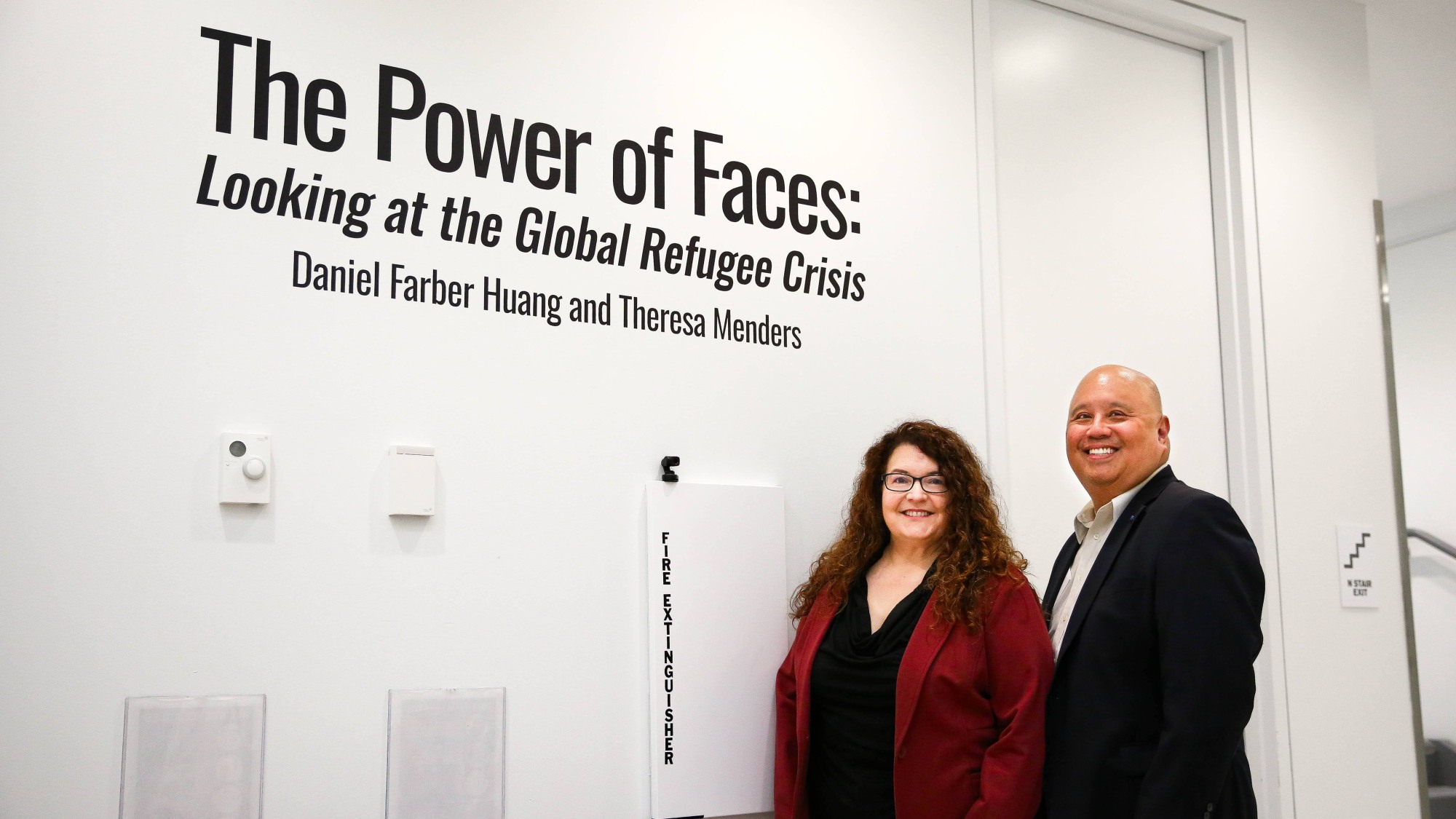

A selection of the couple’s work is on view at Brown University through Dec. 20 in an exhibition titled “The Power of Faces: Looking at the Global Refugee Crisis,” at the Watson Institute for International and Public Affairs. Free and open to the public, the display is part of the institute’s Art at Watson program, which has presented more than 40 installations and events since 2013.

“We felt we could raise awareness of the refugee crisis and be a voice for others who have had theirs taken away because of the situation they are in,” Menders said.

Spanning two floors of the institute’s Stephen Robert ’62 Hall at 280 Brook St. in Providence, the exhibition features photographs of people living in refugee camps in Greece, Bangladesh, Mexico and near the Poland-Ukraine border. The works focus on subjects’ faces, often documented against simple yet colorful backdrops — instead of amid the challenging conditions of the refugee camps. For context, separate photos of the inside and outside of the camps hang alongside the portraits.

This intentional process emphasizes the subjects’ humanity, said Huang, who, with Menders, has been practicing documentary photography since Sept. 11, 2001, when they were living in Manhattan.

Globally, at least 117 million people have been forced to flee their homes due to violence, persecution, human rights violations, or events disturbing public order, and among them are nearly 43 million refugees, according to the United Nations Refugee Agency.