PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — Brown University Ph.D. student Dominique Pablito wears her Indigenous identity proudly.

An aspiring physician-scientist pursuing research in molecular biology, cell biology and biochemistry at Brown, Pablito is simultaneously strengthening support for fellow Indigenous students through mentorship and engagement across campus, including the launch of a new American Indian Science and Engineering Society chapter.

As a fifth-year doctoral student researching treatments for glioblastoma, an aggressive form of cancer, and a member of the Navajo, Zuni and Comanche tribes, she aims to pursue a career in medicine and provide trusted care to tribal communities on reservations.

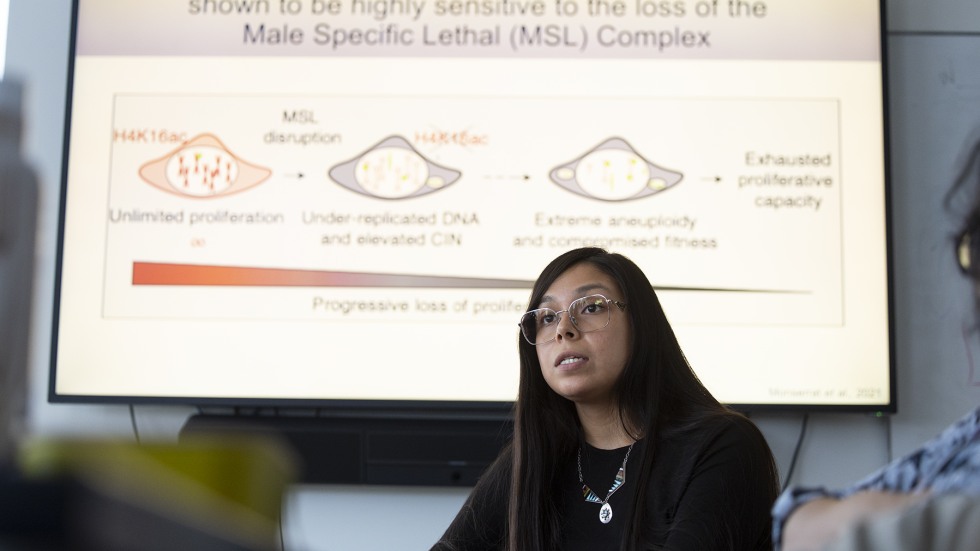

“I want to be very truthful about where I come from,” Pablito told her audience during a recent presentation at Brown in which she spoke about her experiences as an Indigenous student and researcher. She projected photos from the science laboratories in which she worked along with photos of the home in which she lived with a dozen family members on the Zuni Indian Reservation in New Mexico. “My ancestors survived America’s attempt on cultural genocide, but the generational trauma remains. I say this because it is truly monumental to be standing before you giving you this presentation.”

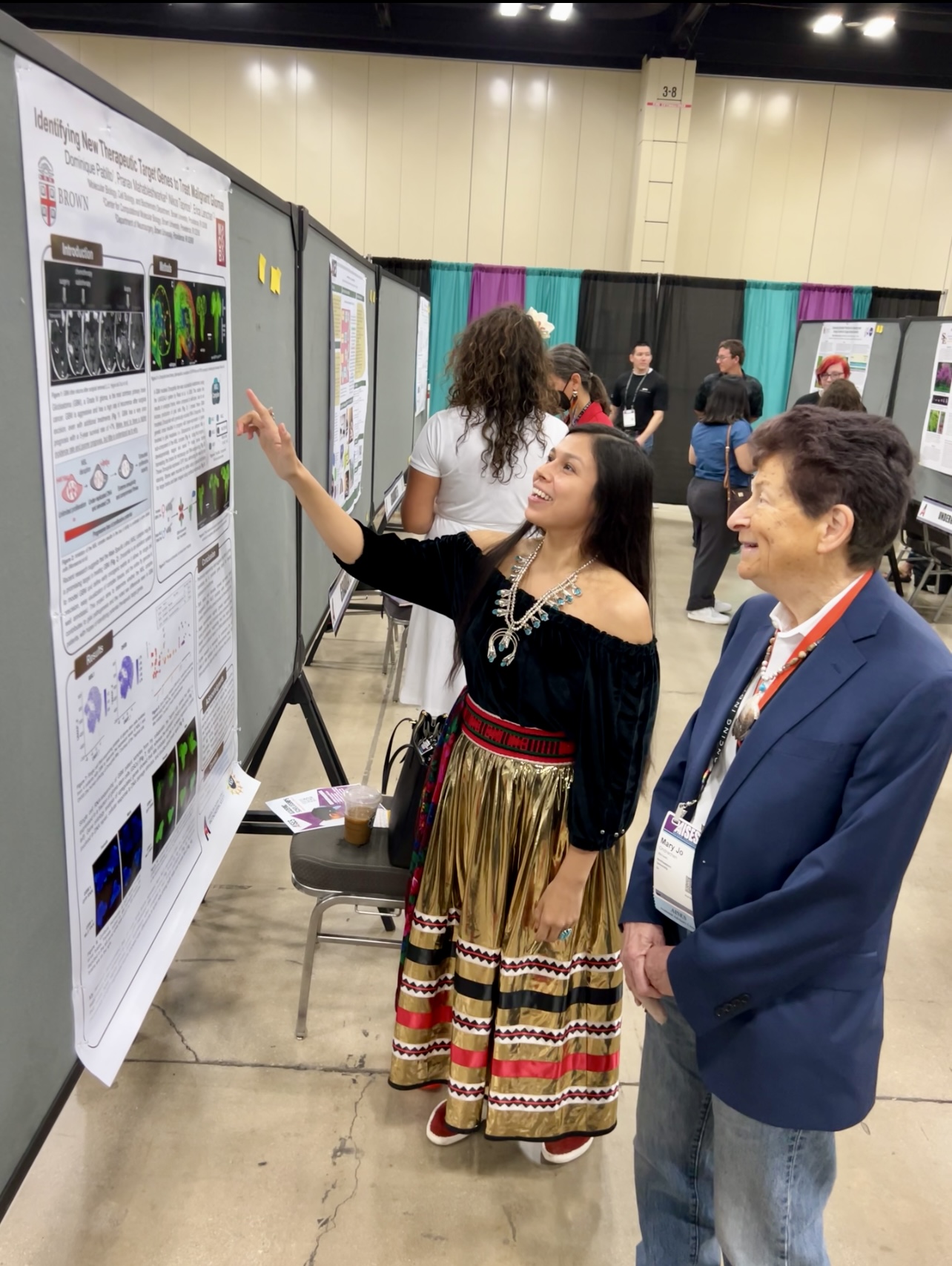

With every academic and professional accomplishment she celebrates, Pablito said she feels a responsibility to members of her community who preceded her and those who will follow. She wears beaded jewelry and Indigenous clothing as business attire regularly, and dressed in full tribal regalia to present her findings about glioblastoma at a poster session in October.

“I’m a mentor for the next generation of Indigenous students, and I’m paving a path for them,” she said.

Embraced at Brown, broadening support to others

Pablito’s doctoral research is focused on identifying new target genes to develop therapeutics to treat glioblastoma, an aggressive malignant tumor that affects the brain.

Her foray into neuroscience was prompted by the experience of her uncle, who had severe epilepsy when Pablito was a child. When his doctors recommended a hemispherectomy — a rare surgery in which half of the brain is removed or severed from the other half — Pablito, who excelled in science at school, pored through medical research to help her family understand what was going on. The more she learned about brain science, the more she wanted to become a neurosurgeon.

Growing up in the Navajo Nation in Utah and the Zuni Indian Reservation in New Mexico, Pablito also witnessed how distrust of the U.S. government often prevented community members from seeking medical care. She watched family members succumb to ailments that could have been intercepted if they’d had a provider they trusted. So she set a goal of becoming just that kind of doctor.