PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — In his much-lauded book “Plantation Goods: A Material History of American Slavery,” Seth Rockman offered a compelling insight on antebellum history by exploring a little-known link between the North and South: the Northern business of making, selling and marketing clothing, tools and even whips to Southern plantations.

Rockman, an associate professor of history at Brown University who will be promoted to full professor of American history on July 1, began research for the book after contributing to the 2006 Report of the Brown University Steering Committee on Slavery and Justice, a groundbreaking report that publicly examined the University’s historical ties to the transatlantic slave trade.

Almost two decades and countless hours of research later, “Plantation Goods” was named a finalist for the 2025 Pulitzer Prize in history, which Rockman learned while teaching a class at Brown in May. When students returned from a mid-class break, he casually told them of the honor.

Almost two decades and countless hours of research later, “Plantation Goods” was named a finalist for the 2025 Pulitzer Prize in history, which Rockman learned while teaching a class at Brown in May. When students returned from a mid-class break, he casually told them of the honor.

“Everyone was yelling, everyone was clapping,” recalled Isabel Cole, a first-year history Ph.D. student and Rockman’s advisee. “I was so glad we all got to celebrate that moment with him. It was so great to witness.”

It was appropriate that Rockman received this news during a class because “Plantations Goods” is, at heart, a Brown book, he said.

“So much of this book was driven by my students,” Rockman said. “They said I was missing out if I limited my research to paper records, they insisted on recognizing economic questions as moral questions and they pushed me to think harder about the relationship of consumer goods to racial categories. This book is about the kinds of interactions between undergraduates and graduate students, and Brown’s institutional culture.”

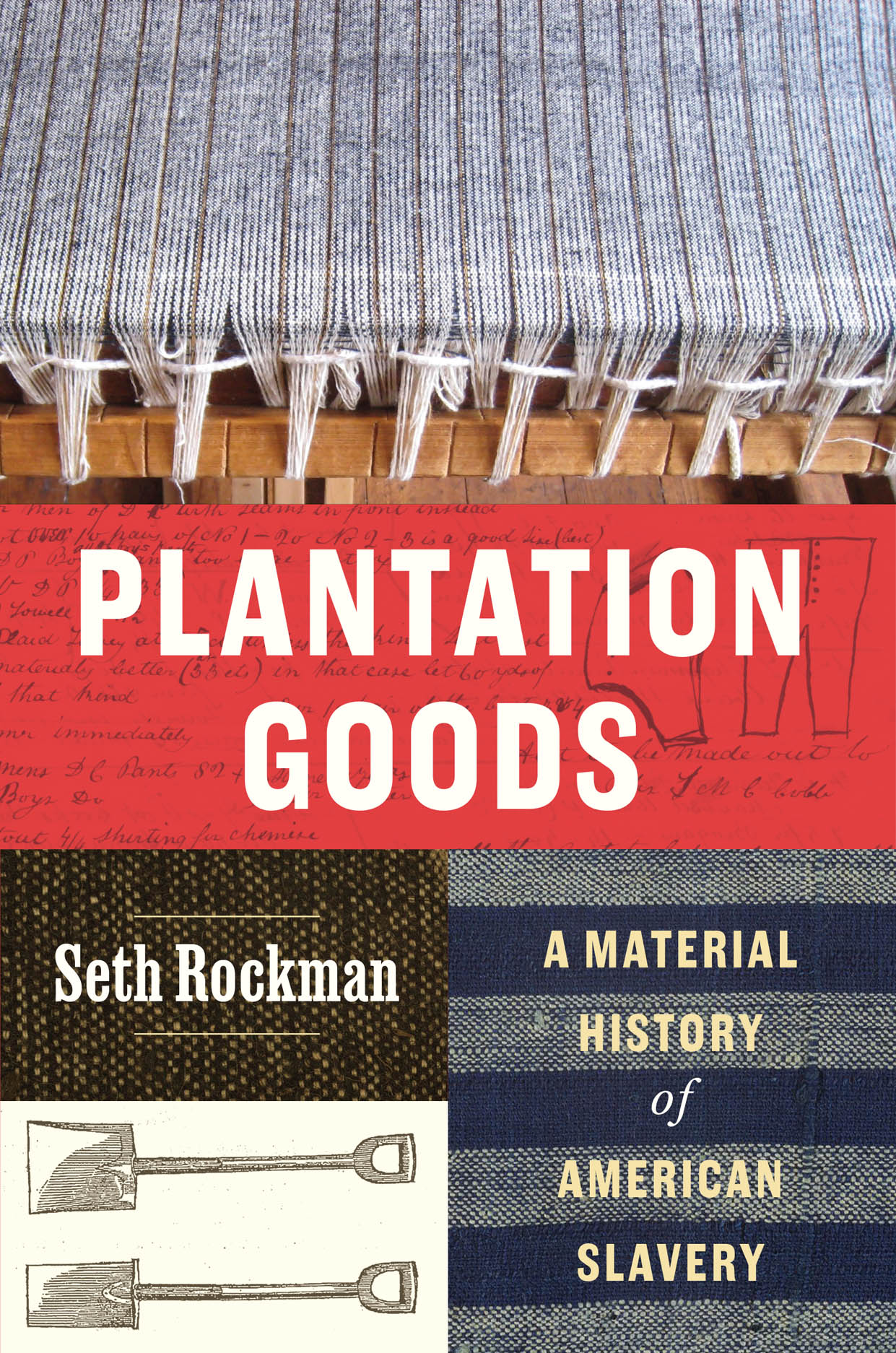

Published in November 2024 by the University of Chicago Press, the book represented the culmination of years of hands-on research to unearth information about the physical materials that shaped Northern involvement in the slavery economy, Rockman said.

“I wanted to tell a story that would get us from New England to the South — from the makers to the users and wearers of these goods and all the different stops on the way — and finally come to the plantation where you’ve got the competing interest of slaveholders butting up against the quest of enslaved people to contest horrific forms of exploitation,” he said.

Weaving historical accounts, drawing present-day lessons

Rockman started his research a few blocks from Brown’s campus at the Rhode Island Historical Society.

“They have this enormous collection of materials: Thousands of letters from slaveholders, Southern merchants and sales agents, all of whom are reporting on the ground, reporting from Louisiana or from Georgia on who’s using these things, how are they using them and what do they have to say about them,” Rockman said.

He also visited seven Southern states to understand how Northern goods were received and the impact they had on plantations. What emerged from his research is a Northern economy propped up, in part, by sales to Southern plantations.

“Seth is at the forefront of thinking about how the 19th century U.S. must be understood in terms of the symbiosis of the North and South,” said Professor of History Ethan Pollock. “His work shows that there was a single, integrated economy.”

In his book, he spotlights factory owners Isaac and Rowland Hazard, brothers who turned their family’s small Rhode Island textile mill into an empire by capitalizing on their Southern connections and designing functional clothing. Each year, either Isaac or Rowland would spend six months traveling across the South to meet with enslaved people and slaveholders. Entrepreneurs like the Hazards balanced the feedback they received from Black laborers with the reality that slaveholders viewed laborers as chattel. There was even a marketing ploy that labeled some products as race specific, Rockman said.

“This category of goods emerges in the textile trade called ‘negro cloth,’” Rockman said. “It doesn’t refer to anything other than a textile intended for Black people to wear. This is part of the way that race is made in America.”

As part of his research, Rockman learned to weave the same type of fabric using the same techniques. A swatch of his woven material appears on the cover of “Plantation Goods” and shows how thorough Rockman’s research was, Pollock said.