PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — A half century ago, the now-Thomas J. Watson Jr. School of International and Public Affairs was little more than an idea languishing in the bottom drawer of Brown University political scientist Newell Stultz’s desk. But over time, his vision expanded into something concrete — first the Council of International Studies and later an institute.

Research and teaching at Brown on international and public affairs flourished in the intervening years, becoming “so much larger and more splendid than my bottom drawer in my office that I couldn’t believe what had happened,” Stultz said in 2017.

On July 1, 2025, the longtime hub for scholarship on the world’s most pressing economic, political, social and policy challenges, became the Watson School of International and Public Affairs. After years of contributions from former institute director Edward Steinfeld (who now holds the honorary title of founding dean of the school) in developing the proposal to create a new school, John N. Friedman — an economics and international and public affairs scholar and leading researcher on social mobility, education and policymaking — will lead the school as its inaugural dean. A series of initiatives to celebrate the launch and advance the institute’s transition into the Watson School will begin when the Fall 2025 semester kicks off.

Founded 46 years ago, what is now the Watson School has grown and changed immeasurably — yet much remains consistent, including its aim to promote a just and peaceful world through research, teaching and public engagement. From cross-border Cold War diplomacy to a U.S. presidential visit to an ever-expanding footprint, here are some of the key milestones in international and public affairs history at Brown.

1979: Building a home for international studies

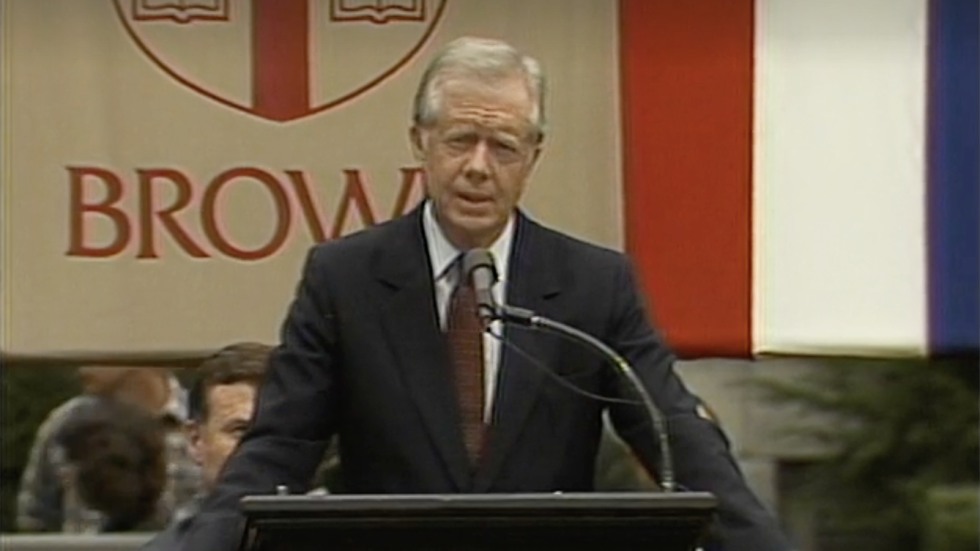

With the Vietnam War concluded and tensions heightening between the United States and the Soviet Union, Brown President Howard R. Swearer noticed a growing trend: Nationwide, college students were pulling back from the study of foreign languages and international affairs.

Describing his concern a few years later in his 1982 Convocation address, Swearer said: “Not only have international studies been less healthy and productive than they should — and could — have been during the last decade, if they are not revitalized soon, before many years have passed, they will be in jeopardy.”

Swearer’s interest in the “internationalization of Brown” inspired the Council for International Studies, launched in 1979 with Stultz at the helm.

“The council is the parliament of international studies at Brown,” Stultz told the Brown Daily Herald in 1985. “It’s both the forum where people discuss issues and an advisory, policy-making department.”

In its early years, the council — which soon evolved into a center — grew to become a bastion for rigorous cooperative scholarship focused on U.S.-Soviet nuclear weapons issues and other East-West security concerns. Unlike most U.S. universities, Brown set out to reach behind the Iron Curtain: It became the first American higher education institution to formally partner with an East German university, and its faculty worked with Soviet scholars to improve relations between the U.S. and the U.S.S.R.

1986: Global luminaries inaugurate an institute

As Americans agonized about the potential for nuclear war with the Soviet Union, Brown students’ interest in international diplomacy grew. The Council for International Studies and other nascent programs thrived, but Swearer knew they would be even stronger together. In an effort to bring programs under one roof in a “collaborative, reasoned and reinforcing manner,” Swearer proposed that Brown create an Institute for International Studies.