Study showcases how complex behaviors can be performed on ‘autopilot’

When completing a routine task like cooking or making a cup of coffee, each motion happens more or less automatically and rarely does one think about how each step impacts the next. A new study by researchers affiliated with the Carney Institute for Brain Science describes how these behavioral processes work.

The paper was published September 13 in the Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition. Theresa Desrochers, senior author of the study and the Rosenberg Family Assistant Professor of Brain Science at Brown University, said the research started with a basic question: “how does practice affect abstract task sequences?” The researchers also wanted to better understand how “the structure of a task sequence influences performance,” said Juliana Trach, who is the paper’s first author.

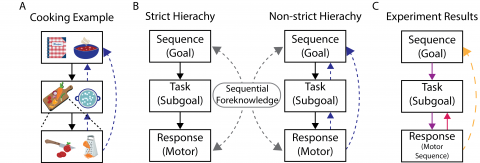

An abstract task sequence is a task that isn’t simply made of motor actions, but rather a “sequence of goal states,” said Trach. When preparing a meal, for example, these goal states might include separate tasks like chopping vegetables or boiling water. The goals may, therefore, be composed of motor actions — like the physical act of moving the knife to cut the vegetables — but they are more than just movement, said Trach.

“We were really interested in digging into how information at these different levels of a task sequence get you to the point of feeling like a difficult task — such as making a cup of coffee, driving to work or making dinner — is actually automatic, easy and less effortful,” said Trach, who graduated from Brown in 2018 with a Bachelor's degree in cognitive neuroscience. Trach conducted this research project for her senior honors thesis.

The researchers investigated how subtasks within an overall task sequence could influence the higher-order goal. “We didn't know, for example, if the lower level goal of boiling water could influence the higher level goal of making the pasta,” said Desrochers, referencing the abstract task sequence of preparing a meal.

The researchers conducted three sequential experiments in order to simulate different variations of task sequences to parse out the role of practice on effectively performing each individual task or the overall goal of the sequence.

Through these experiments, they were able to decouple the impact of practice on motor-related tasks compared to other goal states. The experiments simulated different versions of task sequences by asking participants to make judgements about colored shapes with built-in subgoals and an overarching goal.

The first experiment — in which participants practiced and completed an abstract task simulation — showed that practice facilitated the execution of abstract task sequences, according to the study. But, the researchers saw that practice only had a small effect at the highest order of the hierarchy.

“It was consistent, but it was a small reduction in the amount of time that it takes people to start the sequence,” Desrochers said.

The second experiment added motor sequences and a longer practice time to better replicate the types of task sequences that people might perform in daily life, such as repeating the same procedure and actions each day when making coffee in the morning, Desrochers said. The participants were much faster when the motor action was included, she added.

In the third experiment, the researchers compared tasks that require motor components and tasks without those components. They found that when motor sequences were added to the task sequence, participants didn't need to get a lot of practice to show benefits, Trach said.

The series of experiments helped the researchers determine that these behaviors aren’t all necessarily controlled unidirectionally. While the higher level goal seems to act in a top-down fashion — meaning the overarching goal dictates each subtask — the mid-level and lower-level tasks can influence each other bidirectionally, Desrochers said. The disparity in how the different levels influence each other defies the traditional or intuitive idea that “the big goal is the thing that's directing all these sub goals in terms of what should happen,” she added.

As a next step to this study, the researchers are investigating which brain structures or regions are associated with these processes by employing functional magnetic resonance imaging techniques. According to Desrochers, the bidirectional nature of these processes has implications for how neural signals may interact.

The researchers also want to determine how the results change when the interactions between the lower-level motor actions and higher-level sequences are manipulated in new ways, Desrochers said.