PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — More than 30 fourth-year medical students at Brown University will soon find themselves in the extraordinary position of joining the front lines of the fight against COVID-19 before they even receive their paper diplomas.

As the nation’s hospitals swell with patients and the demand for physicians soars, the Warren Alpert Medical School of Brown University has given fourth-year students who have completed all degree requirements the option to graduate six weeks early and begin working in hospitals immediately, including in Rhode Island.

It’s an unprecedented and historic move for the 45-year-old medical school — one that mirrors the exceptional circumstances brought about by the current global health emergency.

“Since the COVID-19 pandemic arrived in Rhode Island, our medical students have been contributing to the response in numerous ways that have had a significant impact,” said Dr. Jack A. Elias, medical school dean and Brown’s senior vice president for health affairs. “It doesn't surprise me that some who have completed their requirements are opting to graduate early to work in more hands-on roles here and in the places where they will complete their residencies. We could not be prouder of the many ways that our students have stepped up during these difficult times.”

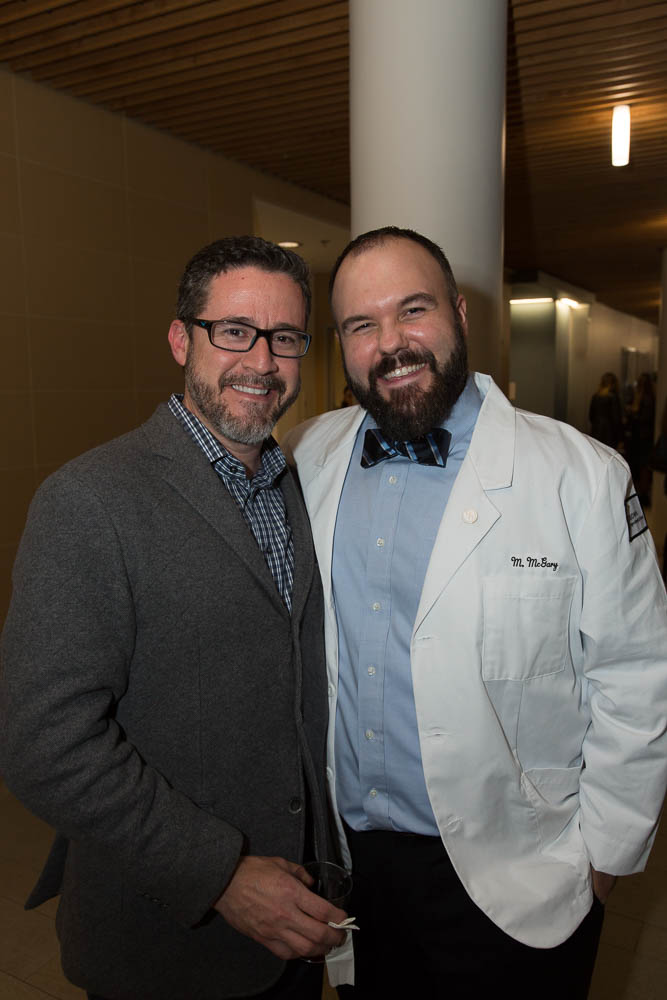

Dr. Allan Tunkel, senior associate dean for medical education at the Warren Alpert Medical School, said that to date, more than 30 of the 132 students in the school’s Class of 2020 have volunteered to graduate early. Medical school leaders made soon-to-be graduates aware of the option on April 7, and on April 15 — following approval by Brown’s Faculty Executive Committee and the Corporation of Brown University’s Board of Fellows — their graduation was official. Degrees were conferred, and the new doctors were free to practice medicine.

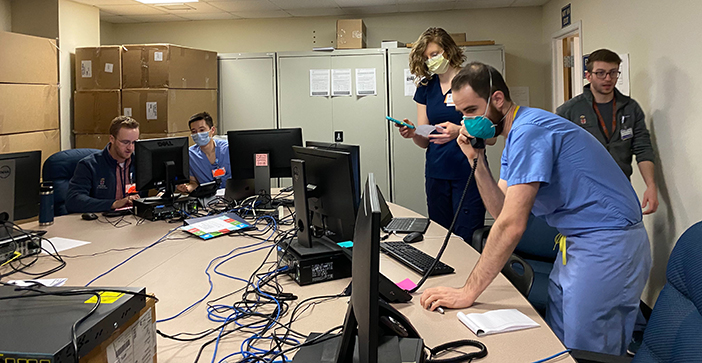

“Medical students have expressed an eagerness to help in any way they can during this crisis,” Tunkel said. “More than 100 medical students have volunteered their time to the Rhode Island Department of Health and to local hospitals, manning call centers, managing medical records and more. Now, they have an additional opportunity to start clinical work — their presence may prove extremely valuable if we experience a surge in patients.”

Tunkel said those who make the entirely optional choice to graduate early have two potential paths: to start work in the hospitals to which they were matched for residencies earlier this spring, which span the nation; or to spend the next four to eight weeks in paid, non-accredited clinical positions in Rhode Island before beginning their medical residencies in June.

Those who choose to stay in the state will receive temporary licenses to practice in Rhode Island and will work for Lifespan or Care New England, the state’s two largest health care systems, which operate most of the hospitals affiliated with Brown’s medical school. Some of Brown’s early graduates may begin work as soon as the week of April 20.

The decision at Brown comes on the heels of similar actions by medical schools in New York and Massachusetts, where local hospitals that needed more trained physicians began to arrange for non-accredited, temporary clinical “residencies” for any newly graduated students who were willing and able to join them. Dr. James Arrighi, director of graduate medical education at Lifespan and a professor of medicine at Brown, said he and colleagues at Brown, Lifespan and Care New England drew heavily from those early states’ arrangements as they formalized a plan for early graduates.

“Many students wanted to contribute clinically, and we wanted to capture their enthusiasm and energy,” Arrighi said. “This is a very rare opportunity for students to see firsthand how government authorities work with hospitals to create a health care infrastructure in times of crisis. And it’s a wonderful opportunity for Lifespan and Care New England to harness students’ particular expertise in, for example, managing electronic records.”

Arrighi said both hospital systems have started to establish field hospitals across the state in preparation for a potential surge in COVID-19 diagnoses. State health officials who have worked with researchers at Brown and other universities to model the disease’s likely spread in Rhode Island have predicted that the number of positive cases will peak between late April and late May.

Lifespan plans to send early graduates to its field hospital at the Rhode Island Convention Center, Arrighi said, where they will provide care for lower-risk patients under the supervision of attending physicians. Tunkel said that Care New England may send some graduates to field hospitals and others to regular hospital wards.