PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — Last summer, demonstrations against police brutality, racism, and white supremacy rocked cities and towns from coast to coast. For many white Americans, the mobilization represented an awakening. For people of color — not to mention scholars of this country’s history — the moment felt all too familiar. But this time one thing was different: for many people, denying that racism is a foundational feature of the United States had become all but impossible.

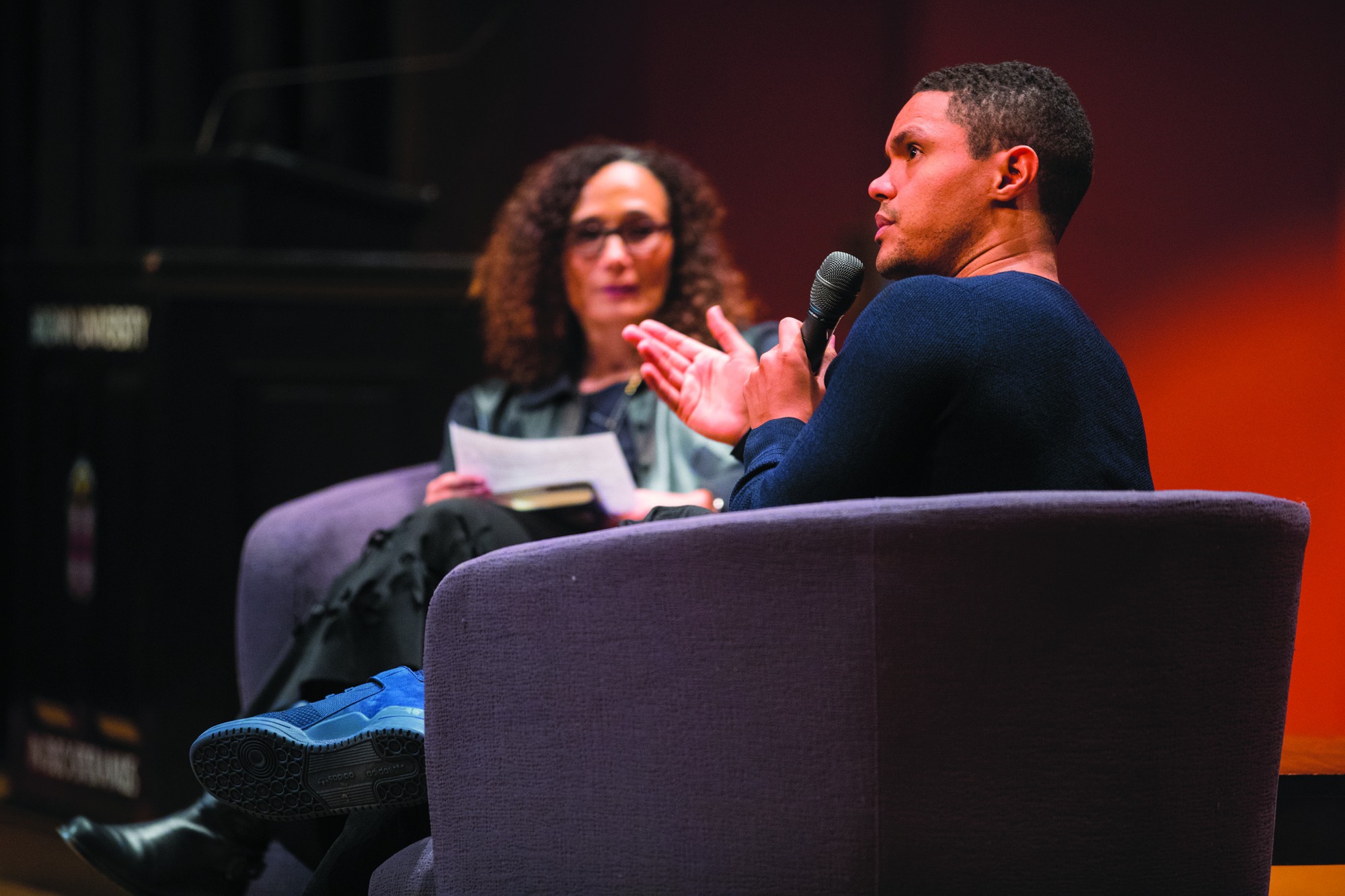

As Brown moved to advance understanding of this profoundly teachable moment, the Center for the Study of Race and Ethnicity in America (CSREA) became the heart of campus efforts. Based on its history, it was natural that, starting in September 2020, the center would host, along with other programs, “‘Race &’ in America,” a year-long series of panel discussions with distinguished researchers from around the university.

Established in 1986, the CSREA was one of the earliest academic centers in the country focused on scholarship on race and ethnicity; at Brown, it is a site for research and dialogue about a topic that has arguably never been more urgent. Its move in 2016 to its current location in Lippitt House, in the heart of campus, mirrors the growing centrality of race and ethnicity in American academic and popular discourse.

“Race is at the heart of whatever happens in our country,” said Tricia Rose, a professor of Africana Studies and, since 2013, director of the CSREA. “If we do not develop a more sophisticated understanding of how race works in American society, we will not be able to produce a just, multiracial democracy.”

What distinguishes racism in America, she says, is the enduring myth that it’s going away. In the post-civil rights era, the fallacy of colorblindness — the idea that if, we refuse to acknowledge race and racial inequality, discrimination will vanish — became entrenched across the political spectrum. The center is using scholarship and discussion to close the gap between the notion that racial and ethnic inequalities are a thing of the past and the glaring truth that they are not.

“Racism has been at the root of our darkest periods, and despite the efforts of many across generations — including civil rights activists, students and scholars — we know that racism is pervasive today, and remains an obstacle to achieving true peace and justice for all,” said Provost Richard Locke. “At Brown, we are committed to revealing and addressing legacies of structural racism and discrimination in our society, and we are fortunate to have significant scholarly resources to draw upon in our work. Chief among these is CSREA, which brings together thought leaders to investigate history and reflect and shape contemporary thought, policy, and practice.”

Timely, relevant and supportive

Rose, whom Ms. Magazine called a "legendary Black feminist scholar," has spent her career studying Black history, culture and sexuality in the post-civil rights era. She is perhaps best known for her pioneering 1994 book, "Black Noise: Rap Music and Black Culture," which helped establish hip-hop as a topic of scholarly focus.

In 2015, she was tapped to direct the new "How Structural Racism Works" series, another collaboration between the Office of the Provost and the CSREA. Based on her ongoing research project, the series offers a campus-wide examination — through lectures, discussions and workshops — of the range of normalized and interconnected policies, practices and attitudes that drive racial inequality in this country.

When Rose accepted the CSREA directorship, she envisioned the center as an “ideas hub” that would spawn new ways of thinking and talking about race, and a widely valued campus asset: productive for faculty, important for students, engaging for the public.

“I have always been invested in making complicated ideas that matter in the world interesting, relevant, and engaging. That to me is the point of being a teacher and a researcher,” Rose said. It’s also the spirit that animates the CSREA.

Through programming and rigorous research, she set about “building a community in conversation about race.” The conversation would be both informed by scholars and accessible to all. The center has since convened many prominent intellectuals, activists and artists. One of the first public programs Rose organized, in 2014, took place shortly after a jury declared George Zimmerman not guilty of the murder of unarmed Black teenager Trayvon Martin: a teach-in featuring experts on the targeting of young people of color.

That same year, as its public programming found its audience on campus and beyond, the center began designing programs to support scholars in myriad ways — eventually offering manuscript workshops, writing retreats, course innovation grants and CSREA faculty grants. Intended to cultivate an intellectual community drawn from across Brown, faculty grants provide funding and staffing for campus events and research groups that faculty members themselves devise according to their academic interests. Over the years, these have included performances, films, seminars and lectures on topics as timely and diverse as school segregation, Latina feminism, indigenous language revival, the whiteness of food movements, and refugees and immigration.

Such a grant enabled Elena Shih, assistant professor of American Studies, to hold a manuscript development workshop in 2019 that helped her refine an edited volume she’d been working on with colleagues around the world. The event brought scholars from Jamaica, Brazil, and Ghana to the center — as well as others who joined via technology — for two days of workshops.

An interdisciplinary research hub

Reflecting her own multidisciplinary approach, Rose says the center invites people from within and beyond the humanities and social sciences to contribute to the conversation.

“If we were just a center that’s a subset of a given discipline, we wouldn’t need to be able to talk across lots of spaces," she said. "We’d have a specialized language, and we would go deep instead of wide. But I think it’s much more important to create an interdisciplinary hub for research and learning. Sociologists have to be able to talk to people in public health, who have to be able to talk to historians, who have to be able to talk to people who work in biomed and genetics. A center should bring people together.”

The center also supports fellowship programs to further the work of graduate students and faculty, and, with the Watson Institute for International and Public Affairs, co-sponsors a postdoctoral research associate in race and ethnicity.

Ronald Aubert, current visiting professor of the practice, appreciates the CSREA’s “unparalleled exposure to senior thought leadership as well as the exciting intellectual energy of emerging scholars across multiple disciplines.”

Former postdoctoral fellow Mariaelena Huambachano credits the support she received from the CSREA with encouraging her to continue her research and her work with the United Nations as an advocate of indigenous people’s rights. Participating in a round table discussion as part of “How Structural Racism Works,” says former Presidential Diversity Postdoctoral Fellow Yalidy Matos, helped her expand her thinking about how structural racism interfaces with immigration, her area of study.